The jazz orchestra was born in the United States in the early years of the 20th century with large groups of musicians assembled to play popular music in dance halls and auditoriums. It wasn’t until 1922 or 1923 when the great pianist and composer Fletcher Henderson (1897-1952) combined several smaller quintets and sextets to form a “big band” dedicated to jazz (or swing) that the jazz orchestra was born.

The jazz orchestra was born in the United States in the early years of the 20th century with large groups of musicians assembled to play popular music in dance halls and auditoriums. It wasn’t until 1922 or 1923 when the great pianist and composer Fletcher Henderson (1897-1952) combined several smaller quintets and sextets to form a “big band” dedicated to jazz (or swing) that the jazz orchestra was born.Inspired by Paul Whiteman’s orchestra, the Henderson big band was set alight by the arrangements of Don Redman – not to mention a soloist by the name of Louis Armstrong – then later by Benny Carter and still later by Henderson himself. Around the same time Duke Ellington moved to Harlem and began building up his own aggregate of exceptionally talented soloists at Harlem’s Cotton Club in the late 1920s and 1930s.

By the 1930s orchestral jazz was thriving. It became the popular music of its day, with many “big bands” playing swing for many appreciative audiences. The major African American bands of the 1930s included the Ellington band, Earl Hines, Cab Calloway, Jimmie Lunceford, Chick Webb and Count Basie. But it was the "white" bands of Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Shep Fields and, later, Glenn Miller that far eclipsed their "black" inspirations in terms of popularity from the middle of the decade.

With the advent of bebop, an outgrowth of some of big-band jazz’s greatest soloists, and rock and roll in the 1950s, the big bands had lost a lot of their luster. The major bands were still performing and recording, but sales and interest in orchestral jazz was sliding downhill rapidly.

Not only were very few bands – with the exception of possibly Stan Kenton, Sun Ra or the Miles Davis recordings with Gil Evans – doing much that was innovative or new in orchestral jazz, but club owners and record companies found it much easier and more affordable to hire or house jazz trios, quartets or quintets.

While Ellington went into the sixties doing some of his very best work - Afro-Bossa, The Far East Suite and Latin American Suite quickly spring to mind - big bands had died out pretty much everywhere except the New York studios. Coincidentally, a whole new stream of young arrangers inspired by the big-band sounds they grew up with caught attention with their lively arrangements for key soloists.

Here are several notable examples of orchestral jazz that came out of the 1960s. Each program is mostly if not exclusively original to the album (hardly any covers or re-imaginings are present, which unfortunately forced out the marvelous Bill Evans Trio and Symphony Orchestra) and in all cases the albums I’ve singled out below are noted for the entirety of their presentation, not just one or two songs (which leaves out many great Don Sebesky arrangements I would have liked including). Please feel free to share any others in the comments section.

Gillespiana - Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra (Verve, 1961): Dizzy Gillespie recorded Gillespiana in November 1960. At that time, Lalo Schifrin, a 28-year-old Argentinean, was his pianist and musical director. Gillespie had first heard him in 1956 - he was struck by Schifrin's writing and asked the young musician to compose something for him. This was the start of Gillespiana, which was described in the original album notes as a "suite form in a concerto grosso format." It is a definitive work, surely one of the composer’s greatest full-scale compositions and, more arguably, the trumpeter’s very pinnacle of performance. It is also one of the finest examples of orchestral jazz ever presented. The five-part suite assigns solo duties within Gillespie’s working quartet: Leo Wright on flute and alto sax, Schifrin, Art Davis on bass and Chuck Lampkin on drums. But it is Gillespie, as it should be, who shines brightest here. The trumpeter occasionally performed the orchestral suite as part of his quintet, notably on November 25, 1960, for the Europe 1 label, but Schifrin’s “Blues” became a staple of the trumpeter’s performances right through to the end of his career. Lalo Schifrin’s The New Continent, recorded by Dizzy Gillespie in 1962 for a 1965 Limelight album (reissued recently on CD in Japan), is another one of the very best orchestral jazz endeavors of the 1960s – one I find I enjoy and appreciate far more and more often than even Gillespiana. Schifrin’s other work from this period continues to rank at the forefront of orchestral jazz and includes such notable titles as Cal Tjader’s Several Shades of Jade (Verve, 1963), Jimmy Smith’s The Cat (Verve, 1964) as well as his own New Fantasy (Verve, 1964).

Gillespiana - Dizzy Gillespie and His Orchestra (Verve, 1961): Dizzy Gillespie recorded Gillespiana in November 1960. At that time, Lalo Schifrin, a 28-year-old Argentinean, was his pianist and musical director. Gillespie had first heard him in 1956 - he was struck by Schifrin's writing and asked the young musician to compose something for him. This was the start of Gillespiana, which was described in the original album notes as a "suite form in a concerto grosso format." It is a definitive work, surely one of the composer’s greatest full-scale compositions and, more arguably, the trumpeter’s very pinnacle of performance. It is also one of the finest examples of orchestral jazz ever presented. The five-part suite assigns solo duties within Gillespie’s working quartet: Leo Wright on flute and alto sax, Schifrin, Art Davis on bass and Chuck Lampkin on drums. But it is Gillespie, as it should be, who shines brightest here. The trumpeter occasionally performed the orchestral suite as part of his quintet, notably on November 25, 1960, for the Europe 1 label, but Schifrin’s “Blues” became a staple of the trumpeter’s performances right through to the end of his career. Lalo Schifrin’s The New Continent, recorded by Dizzy Gillespie in 1962 for a 1965 Limelight album (reissued recently on CD in Japan), is another one of the very best orchestral jazz endeavors of the 1960s – one I find I enjoy and appreciate far more and more often than even Gillespiana. Schifrin’s other work from this period continues to rank at the forefront of orchestral jazz and includes such notable titles as Cal Tjader’s Several Shades of Jade (Verve, 1963), Jimmy Smith’s The Cat (Verve, 1964) as well as his own New Fantasy (Verve, 1964).  Focus - Stan Getz (Verve, 1961): One of Stan Getz’s most unusual albums and surely his very best. Composer Eddie Sauter, arranger of many works by Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Woody Herman and co-leader of the Sauter-Finegan Orchestra in the fifties, provided Getz with a suite of nine pieces that unleash a stunningly unique musical and rhythmic framework from a small group of string players (Getz’s drummer Roy Haynes factors only on the excellent “I’m Late, I’m Late”). Getz, who commissioned the work himself, couldn’t have been more inspired. Sauter’s suite was designed to “draw something out of [Getz] and show him off.” And indeed it does, to a nearly perfect degree. Getz seems to understand with acute accuracy the locus of jazz and classical structures that formed the then emerging “third stream” consciousness. It’s easy to hear here how “third stream” could have become a viable musical genre, despite the fact that neither Getz nor Sauter were at the forefront of this musical movement. Focus is one of the genre’s very best examples of third stream: sensible and structured like so much classical, yet playful and improvisational like the very best of jazz. Getz and Sauter were re-teamed four years later for the soundtrack of the Warren Beatty film Mickey One (MGM, 1965) and then again for some performances in 1966 with Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops. Getz, of course, worked with all the major arrangers during the sixties (Lalo Schifrin, Claus Ogerman, Richard Evans, Johnny Pate and, most memorably, Gary McFarland on 1962’s Big Band Bossa Nova) , producing a great body of orchestral jazz that was far more artistically satisfying than his best-selling, though pleasant, albums of bossa nova. But none are as superbly delivered as the enduringly beautiful and shockingly timeless Focus.

Focus - Stan Getz (Verve, 1961): One of Stan Getz’s most unusual albums and surely his very best. Composer Eddie Sauter, arranger of many works by Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Woody Herman and co-leader of the Sauter-Finegan Orchestra in the fifties, provided Getz with a suite of nine pieces that unleash a stunningly unique musical and rhythmic framework from a small group of string players (Getz’s drummer Roy Haynes factors only on the excellent “I’m Late, I’m Late”). Getz, who commissioned the work himself, couldn’t have been more inspired. Sauter’s suite was designed to “draw something out of [Getz] and show him off.” And indeed it does, to a nearly perfect degree. Getz seems to understand with acute accuracy the locus of jazz and classical structures that formed the then emerging “third stream” consciousness. It’s easy to hear here how “third stream” could have become a viable musical genre, despite the fact that neither Getz nor Sauter were at the forefront of this musical movement. Focus is one of the genre’s very best examples of third stream: sensible and structured like so much classical, yet playful and improvisational like the very best of jazz. Getz and Sauter were re-teamed four years later for the soundtrack of the Warren Beatty film Mickey One (MGM, 1965) and then again for some performances in 1966 with Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops. Getz, of course, worked with all the major arrangers during the sixties (Lalo Schifrin, Claus Ogerman, Richard Evans, Johnny Pate and, most memorably, Gary McFarland on 1962’s Big Band Bossa Nova) , producing a great body of orchestral jazz that was far more artistically satisfying than his best-selling, though pleasant, albums of bossa nova. But none are as superbly delivered as the enduringly beautiful and shockingly timeless Focus. The Gary McFarland Orchestra with Special Guest Soloist Bill Evans (Verve, 1963): A stirring, beautiful score and, ultimately, one of Gary McFarland's finest achievements. McFarland’s painterly talent to evoke specific moods succeeds most brilliantly here. The album is like a soundtrack celebrating the excitement of a big urban wonderland. The compositions are first rate, McFarland's occasional vibes playing is simple and perfect and the backgrounds, composed of a string quartet, the reeds of Phil Woods and Spencer Sinatra and a rhythm section featuring Jim Hall on guitar, Richard Davis on bass and Ed Shaunessy on drums, is poetically sublime. Bill Evans buoys the event with his graceful, individual style, lending a signature that makes this work remarkably moving. The whole album is perfect; a beautiful moment in jazz. McFarland has a number of other orchestral jazz classics to his credit, including Stan Getz’s Big Band Bossa Nova as well his own Profiles (Impulse, 1966), The October Suite (Impulse, 1967) and the underrated Scorpio and Other Signs (Verve, 1968). But he hardly ever touched the sheer graceful beauty of this lovely recording again in his all too-brief career.

The Gary McFarland Orchestra with Special Guest Soloist Bill Evans (Verve, 1963): A stirring, beautiful score and, ultimately, one of Gary McFarland's finest achievements. McFarland’s painterly talent to evoke specific moods succeeds most brilliantly here. The album is like a soundtrack celebrating the excitement of a big urban wonderland. The compositions are first rate, McFarland's occasional vibes playing is simple and perfect and the backgrounds, composed of a string quartet, the reeds of Phil Woods and Spencer Sinatra and a rhythm section featuring Jim Hall on guitar, Richard Davis on bass and Ed Shaunessy on drums, is poetically sublime. Bill Evans buoys the event with his graceful, individual style, lending a signature that makes this work remarkably moving. The whole album is perfect; a beautiful moment in jazz. McFarland has a number of other orchestral jazz classics to his credit, including Stan Getz’s Big Band Bossa Nova as well his own Profiles (Impulse, 1966), The October Suite (Impulse, 1967) and the underrated Scorpio and Other Signs (Verve, 1968). But he hardly ever touched the sheer graceful beauty of this lovely recording again in his all too-brief career. Moment of Truth - Gerald Wilson Big Band (Pacific Jazz, 1963): A classic no matter how you slice it. The second of arranger Wilson’s Pacific Jazz titles and probably the greatest work he’s ever done in a career rife with great work, Moment of Truth features some of the best West Coast players of the time and some of Gerald Wilson’s finest writing. Included on this program of mostly originals is the classic “Viva Tirado” (with solos by Carmell Jones, Teddy Edwards, Joe Pass and Jack Wilson), which was later turned into a pop hit by El Chicano, “Moment of Truth,” the modal “Patterns” (with solos by Wilson, Jones, Pass and Harold Land), “Latino” – all exceedingly memorable in their structure and immortal in their performances. Also notable: Feelin’ Kinda Blue (Pacific Jazz, 1966).

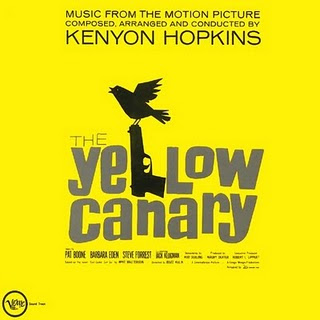

Moment of Truth - Gerald Wilson Big Band (Pacific Jazz, 1963): A classic no matter how you slice it. The second of arranger Wilson’s Pacific Jazz titles and probably the greatest work he’s ever done in a career rife with great work, Moment of Truth features some of the best West Coast players of the time and some of Gerald Wilson’s finest writing. Included on this program of mostly originals is the classic “Viva Tirado” (with solos by Carmell Jones, Teddy Edwards, Joe Pass and Jack Wilson), which was later turned into a pop hit by El Chicano, “Moment of Truth,” the modal “Patterns” (with solos by Wilson, Jones, Pass and Harold Land), “Latino” – all exceedingly memorable in their structure and immortal in their performances. Also notable: Feelin’ Kinda Blue (Pacific Jazz, 1966). Kenyon Hopkins – Perhaps this particular entry is a bit unfair since it’s not one album, but four, and all four albums are soundtrack recordings. Even though Kenyon Hopkins never really made a jazz album, all of his music is imbued with great jazz writing - from scores to films like Baby Doll (1956) to his novelty albums recorded under the aegis of Creed Taylor – and all feature the cream of New York’s finest jazz players, often allotted space, however brief, for improvising in their signature style. Some may dismiss a lot of this evocative music as simply film jazz. But Kenyon Hopkins’ music, especially these four forgotten albums (never issued on CD), is the epitome of emotional grandeur that the best orchestral jazz often achieves.

Kenyon Hopkins – Perhaps this particular entry is a bit unfair since it’s not one album, but four, and all four albums are soundtrack recordings. Even though Kenyon Hopkins never really made a jazz album, all of his music is imbued with great jazz writing - from scores to films like Baby Doll (1956) to his novelty albums recorded under the aegis of Creed Taylor – and all feature the cream of New York’s finest jazz players, often allotted space, however brief, for improvising in their signature style. Some may dismiss a lot of this evocative music as simply film jazz. But Kenyon Hopkins’ music, especially these four forgotten albums (never issued on CD), is the epitome of emotional grandeur that the best orchestral jazz often achieves. The Yellow Canary (Verve, 1963) is Hopkins’ tremendous orchestral jazz score to a forgettable Pat Boone starrer, notable as much for its great music (“The Yellow Canary,” “The Spindrift,” “On the Roof,” “Santa Monica Blues,” “Deserted Canary”) as its memorable performances from star jazz players including Clark Terry, Joe Newman on trumpets, Zoot Zims on tenor sax, Lalo Schifrin on piano and Kenny Burrell on guitar – all of whom get features throughout.

The Yellow Canary (Verve, 1963) is Hopkins’ tremendous orchestral jazz score to a forgettable Pat Boone starrer, notable as much for its great music (“The Yellow Canary,” “The Spindrift,” “On the Roof,” “Santa Monica Blues,” “Deserted Canary”) as its memorable performances from star jazz players including Clark Terry, Joe Newman on trumpets, Zoot Zims on tenor sax, Lalo Schifrin on piano and Kenny Burrell on guitar – all of whom get features throughout. East Side/West Side (Columbia, 1963) is a short-lived New York City-based TV show starring George C. Scott that ran for one season in 1963-64. Hopkins’ music shares much in common with the jazz styles Henry Mancini introduced to television audiences in Peter Gunn. Hopkins scores with a swinging jazz beat, rife with New York studio players that give the whole affair a very East Coast jazz-based sound, particularly the nice but brief features for Phil Woods’s alto sax.

East Side/West Side (Columbia, 1963) is a short-lived New York City-based TV show starring George C. Scott that ran for one season in 1963-64. Hopkins’ music shares much in common with the jazz styles Henry Mancini introduced to television audiences in Peter Gunn. Hopkins scores with a swinging jazz beat, rife with New York studio players that give the whole affair a very East Coast jazz-based sound, particularly the nice but brief features for Phil Woods’s alto sax.  The Reporter (Columbia, 1964) is Kenyon Hopkins’ jazz inflected soundtrack to a short-lived TV show starring Harry Guardino as the titular character, Danny Taylor. Hopkins scores ten pieces here for a 21-piece jazz orchestra (sometimes enhanced by strings) and captures a sound that is much more Ellingtonian than the Mancini-esque East Side/West Side, another “streets of New York” story. There is much effervescent swing and remarkably diverse phrasings throughout and despite such jazz lights as Zoot Sims, Jerome Richardson and Joe Newman in the horn section and Barry Galbraith, George Duvivier and Ed Shaughnessey in the rhythm section, Phil Woods is effectively spotlighted throughout. Nothing at all wrong with that.

The Reporter (Columbia, 1964) is Kenyon Hopkins’ jazz inflected soundtrack to a short-lived TV show starring Harry Guardino as the titular character, Danny Taylor. Hopkins scores ten pieces here for a 21-piece jazz orchestra (sometimes enhanced by strings) and captures a sound that is much more Ellingtonian than the Mancini-esque East Side/West Side, another “streets of New York” story. There is much effervescent swing and remarkably diverse phrasings throughout and despite such jazz lights as Zoot Sims, Jerome Richardson and Joe Newman in the horn section and Barry Galbraith, George Duvivier and Ed Shaughnessey in the rhythm section, Phil Woods is effectively spotlighted throughout. Nothing at all wrong with that.

Mister Buddwing (Verve, 1966) is Kenyon Hopkins’ eclectic orchestral jazz score to a 1966 drama starring James Garner as a man on a quest to regain his memory and find his identity. Surprisingly for Hopkins, the score itself seems to be searching for an identity, traversing various strains of jazz popular in its day, not unlike Quincy Jones’ breakout jazz score to The Pawnbroker (Mercury, 1965) – to which several themes here bear striking similarity. No song really connects with the one that came before it, indicating different players, all of whom are unknown, were allotted for each performance. It’s also surprising that none of the players are named here. Each song seems to feature various sounds and players that producer Creed Taylor was working with at the time, making this as much Taylor’s program as Hopkins’. The oft-sampled “Hard Latin” sounds like it features possibly Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Kenny Burrell on guitar (who probably reappears on “Memory Montage” and “Fiddler’s Walk”) and Larry Young on organ (same goes for “West Side Radio” – but could it possibly be Jimmy Smith here?). Sounds pretty clearly like Grant Green and Larry Young on “R and B 12 (Blues)” but could that be Donald Byrd on trumpet? The vocalists who hum the lines of “Fiddler’s Walk,” “Mister Bee” and “Mirror” sure sound like the singers from the Taylor-produced Up with Donald Byrd. “Lunch Room” sounds like Taylor-produced Kai Winding (who may also be playing here) with Paul Griffin on organ and the Prevailing Winds on vocals. Regardless, it’s a compelling document made whole by Hopkins’ overriding spirit of staying within the jazz tradition and crafting something that swings even though its intention may be otherwise. Best tracks: “The Bridge,” “Hard Latin,” “Fiddler’s Walk,” “Mister Bee,” “West Side Radio,” “R and B 12 (Blues)” and “12/8 Theme.”

The Soul of the City - Manny Albam (Solid State, 1966): The last album Manny Albam (1922-2001) recorded under his own name was probably his very best. Albam had arranged for many jazz orchestras including those of Charlie Barnet, Stan Kenton, Woody Herman, Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins and Joe Newman (who is featured here) and he certainly knows how to swing a big band. An all-original program, The Soul of the City is a musical ode to New York City, featuring some of the city’s best jazz players and studio musicians. Soloists include J.J. Johnson on trombone, Freddie Hubbard and Joe Newman on trumpet, Frank Wess on tenor sax, Phil Woods on alto sax, Jerome Richardson on flute, Hank Jones on piano, Richard Davis on bass and Mike Manieri on vibes. The rhythm section features Jones on piano, Davis (or Ron Carter) on bass and Mel Lewis on drums – many of the same folks who would make up the earliest formation of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. Albam’s program mixes some dynamic charts with occasional street noises (not unlike Kenyon Hopkins’ similar but not as successful “Creed Taylor Orchestra” album from 1959, The Sound of New York) for jazz orchestra with occasional string embellishments. Highlights abound and include “The Children’s Corner” (featuring Richardson, Manieri and Woods), “Museum Pieces” (featuring Woods, Manieri), “A View From the Outside” (featuring Woods, Burt Collins and Johnson), “A View From the Inside” (featuring Newman and Johnson) and “El Barrio Latino” (a brief gem balancing expert horn writing with supple strings) , though the sound effects can be a little overwhelming and annoying at times (“The Game of the Year,” “Tired Faces Going Places” and “Ground Floor Rear”). Reissued in full on the bargain-basement CD Sketches of Jazz – Music From the Book of Life (LRC, 1998).

The Soul of the City - Manny Albam (Solid State, 1966): The last album Manny Albam (1922-2001) recorded under his own name was probably his very best. Albam had arranged for many jazz orchestras including those of Charlie Barnet, Stan Kenton, Woody Herman, Count Basie, Coleman Hawkins and Joe Newman (who is featured here) and he certainly knows how to swing a big band. An all-original program, The Soul of the City is a musical ode to New York City, featuring some of the city’s best jazz players and studio musicians. Soloists include J.J. Johnson on trombone, Freddie Hubbard and Joe Newman on trumpet, Frank Wess on tenor sax, Phil Woods on alto sax, Jerome Richardson on flute, Hank Jones on piano, Richard Davis on bass and Mike Manieri on vibes. The rhythm section features Jones on piano, Davis (or Ron Carter) on bass and Mel Lewis on drums – many of the same folks who would make up the earliest formation of the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. Albam’s program mixes some dynamic charts with occasional street noises (not unlike Kenyon Hopkins’ similar but not as successful “Creed Taylor Orchestra” album from 1959, The Sound of New York) for jazz orchestra with occasional string embellishments. Highlights abound and include “The Children’s Corner” (featuring Richardson, Manieri and Woods), “Museum Pieces” (featuring Woods, Manieri), “A View From the Outside” (featuring Woods, Burt Collins and Johnson), “A View From the Inside” (featuring Newman and Johnson) and “El Barrio Latino” (a brief gem balancing expert horn writing with supple strings) , though the sound effects can be a little overwhelming and annoying at times (“The Game of the Year,” “Tired Faces Going Places” and “Ground Floor Rear”). Reissued in full on the bargain-basement CD Sketches of Jazz – Music From the Book of Life (LRC, 1998).  Nine Flags - Chico O’Farrill (Impulse, 1967): After crafting distinctive works for Machito (Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite with Charlie Parker, 1950) and Benny Goodman (Undercurrent Blues) and arranging for Dizzy Gillespie (the original “Manteca”) and Stan Kenton and more popular oriented fare for Count Basie (Basie Meets Bond, Basie’s Beatle Bag) and Cal Tjader (Along Comes Cal), Impulse gave Chico O’Farrill a chance in 1966 to craft ten pieces “inspired by Nine Flags fragrances.” Of course, nobody even remembers the wacky line of smells. But in an amazing case of marketing cross promotion that outlives the product, the Nine Flags album, which contains ten pieces, not nine(!), is a particularly elegant study in beautiful orchestration and great jazz fortitude. Although it has yet to appear anywhere on CD, the all-original program includes some deliciously beautiful arrangements and a dazzling array of star-studded soloists, from J.J. Johnson (“Live Oak,” “Aromatic Tabac,” “Dry Citrus”), Art Farmer (for whom he arranged the 1959 Aztec Suite - “Aromatic Tabac,” “Royal Saddle”), Clark Terry (“Dry Citrus,” “Panache,” “Green Moss,” “Manzanilla”), Larry Coryell (“Green Moss”) and Frank Wess (“The Lady From Nine Flags”) to Pat Rebillot on piano and Seldon Powell on various woodwinds. The titles have particularly sensorial origins that seem to match perfume varieties, at best, or paint samples, at worst. But they go far into providing particularly enlightening inspiration to the inventive composer and his pen of many colors. The players provide a gorgeous tapestry that lends the soloists a splendidly colorful backdrop worthy of the sexy models featured on the album’s front cover. Highlights include the Latinesque lilt of “Manzanilla” (featuring a phenomenal flute front line and George Duvivier’s tangy bass work), the tremendously spunky Basie-like “Green Moss,” lifted bodily by a spectacular blues solo from Larry Coryell, the brassy yet brief “The Lady From Nine Flags” and the Asiatic exotica of “Patcham”

Nine Flags - Chico O’Farrill (Impulse, 1967): After crafting distinctive works for Machito (Afro-Cuban Jazz Suite with Charlie Parker, 1950) and Benny Goodman (Undercurrent Blues) and arranging for Dizzy Gillespie (the original “Manteca”) and Stan Kenton and more popular oriented fare for Count Basie (Basie Meets Bond, Basie’s Beatle Bag) and Cal Tjader (Along Comes Cal), Impulse gave Chico O’Farrill a chance in 1966 to craft ten pieces “inspired by Nine Flags fragrances.” Of course, nobody even remembers the wacky line of smells. But in an amazing case of marketing cross promotion that outlives the product, the Nine Flags album, which contains ten pieces, not nine(!), is a particularly elegant study in beautiful orchestration and great jazz fortitude. Although it has yet to appear anywhere on CD, the all-original program includes some deliciously beautiful arrangements and a dazzling array of star-studded soloists, from J.J. Johnson (“Live Oak,” “Aromatic Tabac,” “Dry Citrus”), Art Farmer (for whom he arranged the 1959 Aztec Suite - “Aromatic Tabac,” “Royal Saddle”), Clark Terry (“Dry Citrus,” “Panache,” “Green Moss,” “Manzanilla”), Larry Coryell (“Green Moss”) and Frank Wess (“The Lady From Nine Flags”) to Pat Rebillot on piano and Seldon Powell on various woodwinds. The titles have particularly sensorial origins that seem to match perfume varieties, at best, or paint samples, at worst. But they go far into providing particularly enlightening inspiration to the inventive composer and his pen of many colors. The players provide a gorgeous tapestry that lends the soloists a splendidly colorful backdrop worthy of the sexy models featured on the album’s front cover. Highlights include the Latinesque lilt of “Manzanilla” (featuring a phenomenal flute front line and George Duvivier’s tangy bass work), the tremendously spunky Basie-like “Green Moss,” lifted bodily by a spectacular blues solo from Larry Coryell, the brassy yet brief “The Lady From Nine Flags” and the Asiatic exotica of “Patcham” Jazzhattan Suite - Jazz Interactions Orchestra (Verve, 1968): Oliver Nelson crafted some of the era’s finest and most memorable orchestral jazz, so it is quite the task to choose only one of his records as something to be called the best. But Jazzhattan Suite surely ranks at the front of Nelson’s best and most fully realized full-scale orchestral jazz efforts. Commissioned in honor of “Jazz Day,” October 7, 1967, in New York City (and performed in its entirety twice that day, once in Central Park and once at the Metropolitan Museum of Art), this six-piece suite is an outstanding orchestral portrait of an exciting city and its variety of pulsating rhythms. A studio recording of the suite was issued on the Verve label in 1968 under the pseudonymous Jazz Interactions Orchestra, a collection of studio musicians that apparently caused some consternation among certain groups at the time. Oliver Nelson, composer of the jazz standard “Stolen Moments,” had already written some of his best compositions by this point. But he seems to have written some of the very best material of his career for this suite and he reveals a sinewy sense of part writing here, one of the last full-on jazz dates he took part in before immersing himself fully in Hollywood: “A Typical Day in New York,”: “The East Side-The West Side” (featuring Phil Woods on alto sax), the near-standard “125th Street and 7th Avenue” (site of many street-corner speakers, including Malcolm X – featuring Jimmy Cleveland on trombone, Marvin Stamm on trumpet, Jerry Dodgion on alto sax and Zoot Sims on tenor sax), “Penthouse Dawn” (featuring Woods), “One for Duke” (featuring Patti Bown on piano, Zoot Sims on tenor sax, Joe Newman on trumpet and George Duvivier and Ron Carter on bass) and “Complex City” (featuring Woods, Bown, Sims and Newman). Jazzhattan Suite is featured in its entirety on the Mosaic box set Oliver Nelson: The Argo, Verve and Impulse Big Band Studio Sessions. Also worth noting are Nelson’s Afro-American Sketches (Prestige, 1961), Fantabulous (Argo, 1964), The Kennedy Dream (Impulse, 1967) and Black, Brown and Beautiful (Flying Dutchman, 1969) – not to mention Nelson’s lucrative work with Jimmy Smith throughout the sixties, particularly Bashin’ (Verve, 1962), Hobo Flats (Vere, 1963) and, most notably, Peter and the Wolf (Verve, 1966).

Jazzhattan Suite - Jazz Interactions Orchestra (Verve, 1968): Oliver Nelson crafted some of the era’s finest and most memorable orchestral jazz, so it is quite the task to choose only one of his records as something to be called the best. But Jazzhattan Suite surely ranks at the front of Nelson’s best and most fully realized full-scale orchestral jazz efforts. Commissioned in honor of “Jazz Day,” October 7, 1967, in New York City (and performed in its entirety twice that day, once in Central Park and once at the Metropolitan Museum of Art), this six-piece suite is an outstanding orchestral portrait of an exciting city and its variety of pulsating rhythms. A studio recording of the suite was issued on the Verve label in 1968 under the pseudonymous Jazz Interactions Orchestra, a collection of studio musicians that apparently caused some consternation among certain groups at the time. Oliver Nelson, composer of the jazz standard “Stolen Moments,” had already written some of his best compositions by this point. But he seems to have written some of the very best material of his career for this suite and he reveals a sinewy sense of part writing here, one of the last full-on jazz dates he took part in before immersing himself fully in Hollywood: “A Typical Day in New York,”: “The East Side-The West Side” (featuring Phil Woods on alto sax), the near-standard “125th Street and 7th Avenue” (site of many street-corner speakers, including Malcolm X – featuring Jimmy Cleveland on trombone, Marvin Stamm on trumpet, Jerry Dodgion on alto sax and Zoot Sims on tenor sax), “Penthouse Dawn” (featuring Woods), “One for Duke” (featuring Patti Bown on piano, Zoot Sims on tenor sax, Joe Newman on trumpet and George Duvivier and Ron Carter on bass) and “Complex City” (featuring Woods, Bown, Sims and Newman). Jazzhattan Suite is featured in its entirety on the Mosaic box set Oliver Nelson: The Argo, Verve and Impulse Big Band Studio Sessions. Also worth noting are Nelson’s Afro-American Sketches (Prestige, 1961), Fantabulous (Argo, 1964), The Kennedy Dream (Impulse, 1967) and Black, Brown and Beautiful (Flying Dutchman, 1969) – not to mention Nelson’s lucrative work with Jimmy Smith throughout the sixties, particularly Bashin’ (Verve, 1962), Hobo Flats (Vere, 1963) and, most notably, Peter and the Wolf (Verve, 1966). Machinations - Marvin Stamm (Verve, 1968): After a short stint in Stan Kenton’s band, trumpeter Marvin Stamm landed in New York City in 1966 and quickly found favor in the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra (1966-1972) and the Duke Pearson Big Band (1967-1970) as well as earning a place among first-call studio players for some of jazz’s biggest names: Quincy Jones, Oliver Nelson, Cal Tjader, Thad Jones, Wes Montgomery, Stanley Turrentine, Patrick Williams, Kenny Burrell, Frank Foster, George Benson and Gary McFarland. He also played the solo in the original hit version of Paul McCartney’s “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey.” In his solo recording debut, 1968’s Machinations, he is given a jazz-on-the-cusp of rock big band sound by the far too-little known Johnny Carisi (The Birth of the Cool, Gerry Mulligan Concert Band, Into the Hot). With a rhythm section featuring Dick Hyman on piano, Joe Beck on guitar and Chet Amsterdam on bass and a horn section with some of the brightest lights of the New York studios (Urbie Green, Garnett Brown, Jerome Richardson, etc.), Machinations is mostly a program of Carisi originals with intoxicating highlights including “Eruza” (featuring Mortie Lewis on flute and Urbie Green on trombone) and “Jes’ Plain Bread” (featuring a totally funked out Joe Beck). Also great here is Al Kooper’s “Flute Thing,” “Machinations” and “Bleaker Street.” Not enough people know about this great record which, sadly, has never appeared anywhere on CD. Marvin Stamm didn’t record under his own name again until 1983’s Stammpede.

Machinations - Marvin Stamm (Verve, 1968): After a short stint in Stan Kenton’s band, trumpeter Marvin Stamm landed in New York City in 1966 and quickly found favor in the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra (1966-1972) and the Duke Pearson Big Band (1967-1970) as well as earning a place among first-call studio players for some of jazz’s biggest names: Quincy Jones, Oliver Nelson, Cal Tjader, Thad Jones, Wes Montgomery, Stanley Turrentine, Patrick Williams, Kenny Burrell, Frank Foster, George Benson and Gary McFarland. He also played the solo in the original hit version of Paul McCartney’s “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey.” In his solo recording debut, 1968’s Machinations, he is given a jazz-on-the-cusp of rock big band sound by the far too-little known Johnny Carisi (The Birth of the Cool, Gerry Mulligan Concert Band, Into the Hot). With a rhythm section featuring Dick Hyman on piano, Joe Beck on guitar and Chet Amsterdam on bass and a horn section with some of the brightest lights of the New York studios (Urbie Green, Garnett Brown, Jerome Richardson, etc.), Machinations is mostly a program of Carisi originals with intoxicating highlights including “Eruza” (featuring Mortie Lewis on flute and Urbie Green on trombone) and “Jes’ Plain Bread” (featuring a totally funked out Joe Beck). Also great here is Al Kooper’s “Flute Thing,” “Machinations” and “Bleaker Street.” Not enough people know about this great record which, sadly, has never appeared anywhere on CD. Marvin Stamm didn’t record under his own name again until 1983’s Stammpede. Wave - Antonio Carlos Jobim (A&M/CTI. 1968): There has seldom been a sound lovelier in jazz than this remarkably beautiful album. It’s not exactly bossa nova, MPB or even what a good friend I greatly respect calls “new age for the sixties.” Jobim practically invented this sort of thing and displayed it effectively elsewhere. On the albums he recorded for producer Creed Taylor, of which Wave is the second of four, Jobim stuck pretty close to jazz. And while Jobim’s piano, guitar and harpsichord (on “Antigua”) do the singing here, the mood is furthered by the empathic direction provided by arranger Claus Ogerman – the best of all arrangers who ever worked with Jobim. It’s as much Ogerman’s show as Jobim’s. Ogerman highlights throughout with delicately employs strings and piquant breezes of flutes (Ray Beckenstein, Romeo Penque and Jerome Richardson) and trombones (Urbie Green, who solos, and Jimmy Cleveland). It’s a sound that so perfectly accompanies Jobim’s simple flourishes on his intricately constructed and palpably memorable compositions. Indeed, Jobim frequently allows Ogerman’s arrangements to carry the melody and what he does with it is simply magical. Few albums have the power to emote this wonderfully and even though Wave can be - and has been – used as background music, it seldom stays there. It’s the kind of album that always captures attention – even in its lilting lull – and curiously suits every mood. While there is not one low on Wave, highlights on this all too brief album include “Lamento” (featuring Jobim’s only vocal here), “Triste,” “Mojave,” “Antigua,” “Captain Bacardi” and, of course, the title track, which has deservedly become a standard – one of the greatest melodies to come out of the sixties.

Wave - Antonio Carlos Jobim (A&M/CTI. 1968): There has seldom been a sound lovelier in jazz than this remarkably beautiful album. It’s not exactly bossa nova, MPB or even what a good friend I greatly respect calls “new age for the sixties.” Jobim practically invented this sort of thing and displayed it effectively elsewhere. On the albums he recorded for producer Creed Taylor, of which Wave is the second of four, Jobim stuck pretty close to jazz. And while Jobim’s piano, guitar and harpsichord (on “Antigua”) do the singing here, the mood is furthered by the empathic direction provided by arranger Claus Ogerman – the best of all arrangers who ever worked with Jobim. It’s as much Ogerman’s show as Jobim’s. Ogerman highlights throughout with delicately employs strings and piquant breezes of flutes (Ray Beckenstein, Romeo Penque and Jerome Richardson) and trombones (Urbie Green, who solos, and Jimmy Cleveland). It’s a sound that so perfectly accompanies Jobim’s simple flourishes on his intricately constructed and palpably memorable compositions. Indeed, Jobim frequently allows Ogerman’s arrangements to carry the melody and what he does with it is simply magical. Few albums have the power to emote this wonderfully and even though Wave can be - and has been – used as background music, it seldom stays there. It’s the kind of album that always captures attention – even in its lilting lull – and curiously suits every mood. While there is not one low on Wave, highlights on this all too brief album include “Lamento” (featuring Jobim’s only vocal here), “Triste,” “Mojave,” “Antigua,” “Captain Bacardi” and, of course, the title track, which has deservedly become a standard – one of the greatest melodies to come out of the sixties. Coming soon: Orchestral Jazz – The Seventies!

3 comments:

Dear Mr. Payne,

Together with your article of "Jazz goes to the movies/Manny Albam" of last month, this article is revealing to me. I happened to buy that original record at very cheap price last month and I really like it. Now I must definitely find "Nine Flags" and other records you mentioned, particularly the sound tracks. (Of course, I have most of Oliver Nelson, Gerald Wilson recordes.)

Thank you again for your great advice!

Thanks Doug. Can't wait for the 70's orchestral jazz article!

You might want to include an album Edgar Redmond and

The Modern String Ensemble in this section which was an independent project recorded in 1966.

Post a Comment