“A pretty snazzy idea well executed: The label's stars join forces for a set of big-band arrangements of combo-jazz standards. Holding forth swingingly on numbers from the books of Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, and others are such formidable players as Tom Scott, Lee Ritenour, Gary Burton, Eric Marienthal, Randy Brecker, Arturo Sandoval, Kenny Kirkland, and John Patitucci. A pleasing project with immediate jazz radio sizzle.” - Billboard (May 23, 1992)

By the early nineties, Dave Grusin and Larry Rosen’s GRP Records had become such a force of nature, not only in jazz – by then, a pretty smooth kind of jazz – but in the music industry itself. Indeed, by this point, GRP surprisingly inherited the rights to issue and reissue the imposing Impulse catalog as well. Honestly, whoever expected to see the GRP logo on an an Albert Ayler CD? But it happened.

What was little-known at the time and is hardly recalled to this day – this writer pleads guilty to at least on one count here – is that GRP was always devoted as much to mainstream jazz as to whatever you want to call the music that sold discs at the time. GRP issued well-received discs by the Glenn Miller and Duke Ellington orchestras in the eighties as well as Gerry Mulligan’s Re-Birth of the Cool.

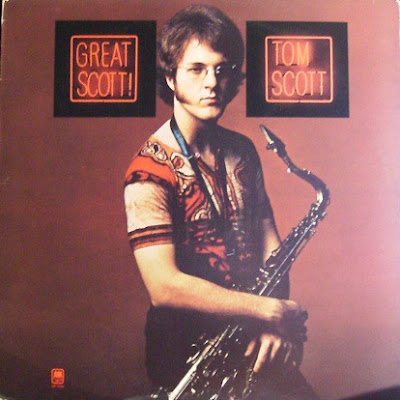

The label also never prohibited its by-then stellar roster of artists to put out the occasional straight-ahead disc. Consider any number of GRP records by Chick Corea, Gary Burton, Lee Ritenour, Tom Scott, Dave Valentin, Eddie Daniels or Arturo Sandoval that swung toward the mainstream.

So, it should have surprised no one when the first GRP All-Star Big Band disc appeared in 1992. Then celebrating its 10th year, GRP had amassed a fairly impressive roster of real jazz talent. Perhaps not since producer Creed Taylor’s CTI All Stars in the seventies and producer/empresario Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic in the fifties had there been a collective this significant in jazz. (There was the Concord All Stars in the eighties, but a group of significantly smaller scale.)

The brainchild of the GRP All-Star Big Band was GRP co-founder and long-time engineer Larry Rosen (1940-2015), who got his start playing drums in Marshall Brown’s Newport Youth Band in the late fifties. That band also included teenage pianist Michael Abene (b. 1942).

Both would go on to other roles in music: Rosen (the “R” of GRP) would team with Dave Grusin to form a production company and, later, GRP Records while Abene went on to arrange for a variety of jazz and pop artists including Maynard Ferguson, Buddy Rich, Liza Minelli, Larry Elgart and the Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra. But both their hearts were rooted deeply with the big bands.

Abene has since gone on to lead the tremendous and highly well-regarded German-based WDR Big Band, where he’s helmed discs with Patti Austin - whom he worked with at CTI in the seventies – Joe Lovano, Paquito D’Rivera, Ali Ryerson, Biréli Lagréne, Bill Evans, Steps Ahead, Steve Gadd and a few of the most exciting Maceo Parker recordings ever waxed.

Rosen asked Abene, who had previously worked on several previous GRP discs, to craft a program of big-band tunes for the GRP roster of recording artists. The goal was not to cover the golden age big-band staples but rather take jazz classics of the fifties and sixties and present them in a big-band format. Or, as the note in the second disc puts it so nicely: “The big band is where jazz songs want to go when they grow up.”

The pair selected tracks they wanted to record and “assigned” songs to arrangers including Tom Scott, Russell Ferrante, Bob Mintzer, Vince Mendoza, Dave Grusin and Abene himself. Then they contracted the musicians and scheduled sessions. Remarkably, then, they assembled a stellar cast of leaders and GRP session players to craft a straight-ahead approach to jazz that was more idealistic and appreciative than commercial at the time.

It’s hard to believe this music came out some three decades ago. It’s hard for me to fathom that it took this long for me to catch up with these discs. From a distance of thirty some years, these discs not only merit renewed attention but manage to exceed all expectation. Honestly, I was imagining a nineties-era fusion take on jazz standards. That’s not at all the case here.

The GRP All-Star Big Band put out three discs between 1992 and 1995, the first two of which were also issued on video in the VHS and Laserdisc formats.

The star power here is fairly dazzling: GRP leaders in their own right include pianist Dave Grusin; trumpeters Randy Brecker and Arturo Sandoval; saxophonists Tom Scott, Eric Marienthal and Nelson Rangell; bassist John Patitucci; drummer Dave Weckl; and the Yellowjackets’ Russell Ferrante and Bob Mintzer (who was helming his own big band at the time). Frequent GRP session players like George Bohannon on trombone, Ernie Watts on saxophones and Alex Acuña on percussion factor on all three discs.

The three discs, particularly the first one, likely sold well. But I wonder whether the folks who bought any of these discs knew what they were getting? I didn’t, which is why I avoided them at the time. And you could find plenty of these discs at second-hand stores back in the day for about a buck a piece. I figure many people were not happy with what they got. They’re pretty easy to find to this day.

Each one of the three of the GRP All-Star Big Band discs were nominated for a Grammy Award, while the last of the three, All Blues, won for Best Large Ensemble Performance. Michael Abene himself was nominated for Best Instrumental Arrangement on each one of the series’ three discs with “Airegin” (1992), “Oleo” (1993) and “Cookin’ at the Continental” (1995) while Tom Scott was nominated for “Stormy Monday Blues” (1995).

GRP All-Star Big Band (1992)

Sonny Rollins’ ”Airegin” serves as the GRP All-Star Big Band’s opening salvo. No one familiar with GRP at the time was likely expecting anything like this: an acoustic killer that swings ferociously. Michael Abene serves up a magnificent arrangement that has real grit and stamina. While he had previously, although very differently, arranged “Airegin” for Maynard Ferguson (in 1964 and 1977), this “Airegin” is a real knockout.

The dueling horns of Ernie Watts (on tenor) and Tom Scott (on alto) are reminiscent of those old “Jazz at the Philharmonic” jams, but considerably more congenial and much more enjoyably compacted. That cordiality is striking: these leaders never let their egos get in the way. Their music is in service of the band – just as it was in those great big bands of yore.

But “Airegin” is just the beginning. Abene really shines on Horace Silver’s 1959 jazz standard “Sister Sadie” (recall, too, that Silver was pianist on the original “Airegin”), letting George Bohannon’s growling trombone positively dance with Eric Marienthal’s barking alto.

The Tom Scott-arranged “Blue Train” nicely updates John Coltrane’s 1957 classic with solos by Nelson Rangell (on alto sax), George Bohannon (doing his Curtis Fuller part), Bob Mintzer (on tenor sax) and Russell Ferante (on piano) soloing.

Wayne Shorter’s jazz standard “Footprints,” (1966), arranged by Yellowjacket Bob Mintzer, benefits mightily by pianist David Benoit and guitarist Lee Ritenour. Trumpeter Sal Marquez suggests what Freddie Hubbard might have contributed to this track had he been included (he wasn’t). Ritenour is absolutely joyous here.

Mintzer’s magnificently arranged “Manteca” is derived from the 1947 Afro Cuban jazz standard by Dizzy Gillespie, Chano Pozo and Gil Fuller. Flautist Dave Valentin – who previously recorded a fiery version of the song with Jorge Dalto in 1984 – tackles one of the leads here. Trumpeters Arturo Sandoval and Randy Brecker are all in for dueling solos while Kenny Kirkland wows on piano and both Dave Weckl and Alex Acuña power up the percussion beyond anything Dizzy could have envisioned. (Mintzer even nicely quotes Kool and the Gang’s “Let’s Go Dancing [Ooh La La]” here.)

Dave Grusin’s elegant yet Grusin-y arrangement of Herbie Hancock’s standard “Maiden Voyage” (1965) may not be to all tastes, probably because it is so Gruisin-y. But this listener readily appreciates one great pianist’s take on another great pianist’s work, particularly because of who those players are. Bob Mintzer offers a lovely solo on bass clarinet that nicely tips a hat to Mwandishi/Headhunter Bennie Maupin.

I am also especially impartial to the Vince Mendoza-arranged “Round Midnight,” Thelonious Monk’s 1943 jazz standard. It begins in a mode that Gary McFarland (who Abene worked with briefly in the late sixties) then offers up lovely solos by Ernie Watts, Gary Burton (who also worked with McFarland) and (briefly) Dave Grusin, all in midnight mode.

Others are likely to find favorites here I haven’t mentioned. It’s really that appealing. Much to my surprise, there is much to enjoy here, particularly upon repeated listens.

Zan Stewart’s surprisingly extensive liner notes are interesting and informative. But this is the only one of the big band discs featuring the GRP all-stars Lee Ritenour (who solos on “Footprints” and “Spain”), Kenny Kirkland (“Sister Sadie,” “Manteca”), Dave Valentin (“Manteca,” “Spain”) and Sal Marquez (“Seven Steps to Heaven,” “Footprints”).

While the GRP All-Star Big Band’s eponymous debut may not be the most ambitious of collective’s three discs, it is surely the best.

Dave Grusin Presents GRP All-Star Big Band Live! (1993)

One year after its eponymous debut, the GRP All-Star Big Band was invited to mount a seven-city tour of Japan. The concerts were intended to promote Panasonic’s Digital Compact Cassettes (DCC), a recently-launched competitor to DATs (both formats soon fizzled out). But it was enough to bring all these leaders together for concert presentations. It’s unclear if the collective ever performed live again but probably unlikely.

Added to the group this time out are Chuck Findley and Byron Stripling on trumpet and then-recent GRP signee Philip Bent on flute. The GRP All-Star Big Band revisits its arrangements of “Manteca,” “Blue Train” and “Sister Sadie” (here adding solos by Gary Burton and Eddie Daniels) from the previous record.

Tom Scott is credited as bandleader while Dave Grusin, who makes a much more forwarded presence here, gets the billing that gives the disc its name: Dave Grusin Presents GRP All-Star Big Band Live!.

The disc opens with Michael Abene’s dazzling arrangement of Sonny Rollins’ 1954 jazz standard “Oleo.” It is an exciting performance – loaded with formidable solos by Eddie Daniels, Gary Burton, Chuck Findley, Eric Marienthal, Dave Grusin, Russell Ferrante and Dave Weckl – that sounds more apt as the set’s closer than its introduction. I would have opened with “Sister Sadie” and closed with “Oleo.”

The highlight for this listener is Grusin’s contemporary-sounding take on “My Man’s Gone Now,” from George Gershwin and DuBose Hayward’s Porgy and Bess (1935). This rendition is pretty much the same arrangement that Grusin performed on his 1991 disc The Gershwin Connection (also with Marienthal, Patitucci and Weckl). But the band is all in here with Randy Brecker and Eric Marienthal delivering terrifically rousing solos.

Also reprised from The Gershwin Connection is the charming piano duet on “S’ Wonderful.” Here, Russell Ferrante swaps seats with Chick Corea from the earlier disc for a pas de deux. The big band sits out – disappointingly. With all the Gershwin heard here, it’s worth noting that “Oleo” is based on the same chord progressions as George and Ira Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.”

Another highlight is surely Louis Prima’s “Sing Sing Sing” – also sounding more contemporary – with compelling solos by Eddie Daniels, Gary Burton and, notably, Dave Weckl. This version is similar to the Daniels/Burton quartet version heard on the pair’s 1992 Benny Rides Again - with an electrifying horn orchestration added by Tom Scott that reminded me of a Michael Small cue riffing off “Sing, Sing, Sing” from the 2001-2002 Nero Wolfe TV series.

Also new to this collection is the arrangement by Gary Lindsay (not “Lindsey” as listed in the disc’s credits) of Ray Noble’s 1938 big band standard “Cherokee.” This version of the song originates on Arturo Sandoval’s 1992 disc I Remember Clifford, where Sandoval overdubbed four trumpet parts. Here, the entire trumpet section – Sandoval, Randy Brecker, Chuck Findley and big-band vet Byron Stripling – get into a friendly battle royale that really wound the audience up.

The audience is Indeed enthusiastic and appreciative throughout, even on the disc’s odd duck: Dave Grusin’s original, “Blues for Howard,” a song I don’t think Grusin had previously recorded and one that hardly rates as big-band fare. Presumably named for guitarist Howard Roberts, this one’s little more than a fairly open-ended quintet piece with horn charts and Tom Scott’s terrific, yet lone solo on the disc.

All Blues (1995)

The third and final GRP All-Star Big Band disc has more than a little different flavor. Now there is a “theme”: the blues and its ever-abstract truth. All-stars Gary Burton and Eddie Daniels are gone. And the new all-stars joining the fold include Ramsey Lewis (on three songs); Chick Corea and Michael Brecker (on two songs) and blues legend B.B. King (on one song). As of this writing, sadly, all four of those have since passed on.

Evidently, the disc started off as a Horace Silver tribute. During the disc’s planning, however, a number of natural-event setbacks convinced all concerned to do an album of...the blues.

These are blues that run the gamut and take in many shades of the genre. It’s a gamut that gamely recognizes anything with “blue” in the title as “the blues.”

The disc opens with Michael Abene’s splendid take on Horace Silver’s fast blues “Cookin’ at the Continental.” The song dates back to a 1959 Silver album called Finger Poppin’ and is named for a club in Brooklyn Silver’s quintet played at. Abene’s arrangement fuels terrific solos by Arturo Sandoval on trumpet and Tom Scott on tenor sax, the former blowing props to Blue Mitchell and the latter swaggering like Junior Cook.

Dave Grusin offers an especially rousing take on Silver’s Latinate standard “Señor Blues” (1956). Something of a hit in its day – and one of Silver’s best-known pieces – this “Señor” offers nods to Nelson Rangell on flute (obviously standing in for Dave Valentine but sounding remarkably here like Hubert Laws), Ramsey Lewis (and not Grusin!) on piano and Arturo Sandoval on trumpet.

(For another striking big-band swing on “Señor Blues,” consider trombonist Urbie Green’s take on the tune, the title track to his 1977 album on CTI, arranged beautifully by David Matthews and featuring the tenor sax of Grover Washington, Jr.)

Another of the disc’s highlights is Dave Grusin’s mesmerizing take on the classic Miles Davis “sketch” “All Blues” (1959). Again, it is fascinating to hear Grusin take on another pianist. In this case, Grusin sits in Bill Evans’ chair, a seat he rarely occupied (Grusin waxed two tracks for a 2002 Japanese set called Portrait of Bill Evans). Solo kudos go to Grusin and Randy Brecker on trumpet, who like Grusin, hardly needs to prove himself to anyone.

John Coltrane’s little-known “Some Other Blues” – originally from the 1961 album Coltrane Jazz - was recorded eight months after the original “All Blues” with the same rhythm section. Tom Scott serves up a lovely arrangement here with solos by Chuck Findley on trumpet, Bob Mintzer on tenor sax and Russell Ferrante on piano.

The appearance of Chick Corea and Michael Brecker here – both of whom were said to be unable to appear on at least the first of the big band’s discs – is likely to appeal to many. But their two features, Corea’s Russell Ferrante-arranged “Blue Miles” (originally on the 1993 Chick Corea Elektric Band II album Paint the World) and the Abene-arranged “Mysterioso/Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are” don’t give them much to work with. They’re up to the task but both songs sound out of place here.

Shortly after All Blues was recorded, Dave Grusin and Larry Rosen left GRP. Many of the other GRP all-stars soon followed suit. The feeling of “one last hurrah” hangs over the disc. “I love the way this album sounds,” said Michael Abene in the album’s notes. “It’s got a little hair on it, which I think is cool. I didn’t want this album to be too slick because this is the blues.”

This is, indeed, the blues. But it’s also GRP and slick is what they do best. The “hair” here might be the result. Had the producers stuck to their original vision of dedicating an entire set to Horace Silver – who was in the midst of a “comeback” at the time – they might have come up with a real winner. The two Silver tunes here, in fact, yield gold.

This survey of various kinds of blues comes across as more of a hodge podge that could have used a bit more focus. So, last hurrah or last gasp? Maybe it’s just a way to go out.

All three GRP All-Star Big Band discs were reissued in 1995 on the budget Jazz Heritage label and have occasionally reappeared in Japanese CD reissue campaigns.