Saturday, July 06, 2024

Thursday, November 23, 2023

Paul Desmond featuring Gabor Szabo – “Skylark” at 50

Alto saxophonist Paul Desmond (1924-77) is best remembered as the linchpin of the Dave Brubeck Quartet from 1951 to 1967. During that period, Desmond recorded several piano-less albums of his own with Gerry Mulligan and others, most notably, with guitarist Jim Hall. And, lest one forgets, Desmond provided the Brubeck quartet with its signature hit, “Take Five” – released in 1959, but which, surprisingly, did not catch on until 1961.

Once freed from Brubeck, however, the distinctive Desmond was wooed by producer Creed Taylor to record two superb albums for the A&M/CTI label. After recording his final A&M album, the Don Sebesky-produced Bridge Over Troubled Water, in 1970, the lazy Desmond largely receded from the music scene.

Not much of a club-date player, Desmond would reunite with Brubeck in 1972 for the Two Generations of Brubeck, playing the festival circuit on the East Coast as well as those in Europe, Australia and Japan.

By this time, producer Creed Taylor’s now independent CTI label had become the most artistically and commercially successful of all jazz labels. Taylor invited the ever-skittish Desmond back to the fold, where he initially made guest appearances on such CTI recordings as Jackie & Roy’s “Summer Song/Summertime” from Time & Love (1972) and Don Sebesky’s “Song to a Seagull” and “Vocalise” from Giant Box (1973).

The CTI roster also now included the Hungarian guitarist Gabor Szabo (1936-82), who had previously put out a spate of well-regarded records on the Impulse, Skye and Blue Thumb labels. Taylor had already issued Szabo’s CTI debut, Mizrab, in April 1973, while the guitarist recorded his CTI follow-up, Rambler in September of that year.

In an audacious bit of casting, producer Creed Taylor paired these two individualists – seemingly one’s oil to the other’s water – for Skylark, an album that shouldn’t work…but does. Tremendously well, in fact. It’s one of those things that sounds crazy in the telling but, in all due credit to the producer, is surprisingly magnificent to hear.

Taylor could have chosen – or overdubbed – a guitarist like CTI All Star George Benson or even Jim Hall, who would also come to CTI in the following months. Both are “prettier” guitarists, seemingly suitable to Desmond’s milieu. But if Taylor (who did not drink) was mixing a cocktail, this is a Long Island Iced Tea: it goes down easy, but it’s stronger than one might guess or assume.

Recorded over three dates in late November (with Gabor Szabo) and early December (without Szabo) 1973, Skylark introduces Paul Desmond to the seventies-era “CTI sound” and formula. There’s an original, a pop tune, a standard and not one but two jazzed-up classical pieces.

Desmond is backed by a small group of CTI All Stars including Bob James on keyboards, Ron Carter (who appeared on Desmond’s previous A&M albums) on bass and Jack DeJohnette – in the next-to-last of his CTI recordings – on drums.

Added to the mix are the backgrounded guitarist Gene Bertoncini, Ralph MacDonald on percussion (“Was a Sunny Day” only) and George Ricci on cello (“Music for a While” only). CTI’s in-house arranger, Don Sebesky, who had provided the larger frameworks for Desmond’s previous A&M albums, provides minimal but beautifully consequential direction here.

Although Gabor Szabo gets featured billing on Skylark’s cover, the guitarist appears on only two of the original LP’s five songs: “Take Ten” and “Romance de Amor.” (Szabo returns, however, for bonus tracks issued decades later on CD.) The great Gene Bertoncini (b. 1937), on the other hand, appears throughout – but hardly ever in a solo capacity.

If this seems odd, it’s worth remembering Creed Taylor’s first recording with Szabo – Gary McFarland’s 1965 album The In Sound (Verve) – also paired the Hungarian guitarist with a second guitar: no less than the great Kenny Burrell, who, at that time, was much better known and, himself, a particularly well-documented soloist.

Perhaps Taylor felt that, while Szabo may have been a strong and compelling soloist, he was not necessarily the ideal accompanist or rhythm guitarist for a session – particularly for someone of Paul Desmond’s disposition or demeanor. Szabo himself likely picked up on Taylor’s insight on The In Sound as he recruited guitarist Jimmy Stewart to join his own memorable quintet, which unfortunately only lasted from 1967 to 1969.

Suffice it to say, the two guitarists work (or, more accurately, are recorded) superbly well together on Skylark. But, more important, there is an unexpected kismet in Desmond’s sweet and Szabo’s sour, a mix that makes Skylark a highlight in both the saxophonist’s and especially the guitarist’s discographies.

Skylark opens with what is probably Paul Desmond’s second-best-known composition of all time. Like the enduring Dave Brubeck Quartet hit “Take Five,” its sequel, “Take Ten,” is also written in 5/4 time, or, more to the point here, 10/8 time. Desmond originally wrote and recorded “Take Ten” for his 1963 solo album of the same name in a superb quartet performance featuring Jim Hall on guitar.

Here, “Take Ten” is delivered by the core quintet – and, to these ears – in a darker, more deeply considered performance (Bertonicini seems to sit this one out). Szabo provides the rhythm support, aided in no small measure by Bob James’ Fender Rhodes. Desmond solos as mellifluously as ever while Szabo takes a hypnotic solo that recalls his spellbinding glory days.

Following the intoxicating opener, the nine-plus-minute “Romance de Amor” makes for the album’s most compelling highlight. It is an unusual choice, but a superb one. It also spotlights the best work the group and its individuals offer on the record.

”Romance de Amor” is believed to have been written for solo guitar in the late 19th century. The Spanish or South American piece is considered “Traditional” as its origins have long been in dispute.

The three-part structure of the song is superbly and subtly arranged by Don Sebesky as follows: 1 = Gene Bertoncini plays the Spanish section on solo guitar. The line is repeated by Gabor Szabo with Bertoncini, Ron Carter on bass and raga-like percussion (00:00 to 00:57). 2 = Paul Desmond with rhythm section in a bossa mode (000:58 to 01:23). 3 = Sebesky omits the original theme’s third part for a more dramatic raga-like structure that Desmond beautifully improvises over (01:24 to 02:29).

Desmond continues to improvise over changes to sections 2 and 3 (02:29 to 03:20) – while Szabo strikes several notes around the 02:55 mark. Szabo solos hypnotically over a vamp that riffs off a minor chord stoked by Carter’s bass with occasional keyboard and drum swells (03:21 to 05:48).

Bob James takes a laid-back solo with Carter on bass and DeJohnette supporting on an intuitive heartbeat bass drum. This eventually leads to sparring with Szabo on guitar (05:48 to 08:08). Desmond returns to riff off section 2 until the group closes out the tune by returning to the first section. It is a marvelous and memorable performance.

Once upon a time, this listener would let the first side of this record play through to the end, then pick up the needle and play it all over again. For hours. Whatever one may assume about the Desmond-Szabo pairing is instantly dispelled by the simpatico aural chemistry they make over these two songs. Desmond shines in this electric context, while, for Szabo, these pieces (coupled with the first side of his own CTI album Mizrab) represent the very best of the guitarist’s work in the seventies.

Flipping the original record over, however, was always a bit of a jolt. There is a sense as though this side comes from another album altogether. Or, at least another recording session – which it pretty much was.

First of all, despite his co-star billing, Szabo is gone. It’s difficult to say why: bonus tracks to a CD version of Skylark released years later reveal the guitarist recorded perfectly fine takes of at least two of the album’s three remaining tracks. But…

It was likely the sort of thing that soured Szabo on CTI (in a DownBeat Blindfold Test the guitarist later slyly referred to Creed Taylor as “my current landlord”). But given Taylor’s sensibilities, the producer may have struggled a bit more than usual with what to do with – or for – the guitarist, particularly as a sideman or in this Desmond situation.

Side two opens with a breezy bossa take of Paul Simon’s Jamaican-lite “Was a Sunny Day.” The Simon original featured fellow CTI recording artist Airto (Moriera) – who appeared on the earlier Desmond albums Summertime and From the Hot Afternoon, but, for whatever reason, is not heard here.

The song originally factored on Simon’s 1973 album There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, an album that also featured the original version of “Take Me to the Mardi Gras,” which Bob James would, of course, turn into a sample classic on his 1975 CTI album Bob James Two.

In another unique programming choice, Skylark takes up “Music for a While” by the English Baroque composer Henry Purcell (1659–95). Originally scored for soprano (voice), harpsicord and bass viol, “Music for a While” is the second of four movements originally written as incidental music for John Dryden’s play based on the story of Sophocles’ Oedipus.

But a second classical theme on one jazz album was maybe a bridge too far – and likely sabotages the saxophonist, however beautifully he navigates this sea’s particular chop.

”Music for a While” opens with a dreamy, echo-y Fender Rhodes trill (similar to the one James used for Eric Gale’s “Forecast” earlier that year) that leads into the main melody. George Ricci – picking up the part originally intended for Szabo – is brought in on cello to do a lovely pas de deux with Desmond’s alto. Sebesky sets the song in a typical Spanish mode before lurching into the delightful changes of “Django.” It’s a lovely performance, but – rather oddly – mostly unmemorable.

Surprisingly, Desmond had not previously recorded Hoagy Carmichael’s “Skylark.” Even more remarkably, Dave Brubeck – in or out of the original quartet – never recorded “Skylark” either.

Here, “Skylark” opens as a duet between Desmond and Gene Bertoncini before yielding to the quartet with Carter and DeJohnette. In the original album version, Bob James comes in for a pretty but seemingly tentative-sounding piano solo (perhaps Dave Brubeck was whispering in his ear). The piano solo heard here supplants a perfectly wonderful Jim Hall-esque solo delivered by Bertoncini on the “Skylark (alt take),” first released in 1997.

There was likely a version of “Skylark” recorded that featured Gabor Szabo instead of the prettier and less rough-hewn-sounding Bertoncini. But, if so, it has not yet been heard. “Skylark” seems just the sort of thing Szabo would have gravitated toward, yet it never factored in his own repertoire. If, indeed, Szabo recorded the tune here, he was no doubt insulted by the slight this Skylark delivered.

Sebesky would go on to arrange “Skylark” again for CTI albums by Roland Hanna (1982) and Jim Hall (1992). He also arranged a version of “Skylark” for a 1980 album by Italian flugelhorn player Franco Ambrosetti that featured Skylark bassist Ron Carter.

Skylark was released in May 1974 to generally favorable reviews that mostly commented on the distinctive alto saxophonist’s tone. To wit:

“The altoist works in a coolly relaxed environment, almost icy but nonetheless in a constant state of fluid motion” (Billboard). “His feathery tone is unmistakable. Light and airy and filled with personal style, especially ‘Was A Sunny Day’" (Walrus). “Desmond is an outstanding player whose work is more soothing than it is vital…[with] an excellent rhythm section playing a variety of material, mostly of the dreamy kind” (Asbury Park Sunday Press).

DownBeat’s Charles Mitchell awarded the album five stars in the music magazine’s July 18, 1974, issue (the same issue that gave Szabo’s own CTI album Rambler a mere two and a half stars): “What a beauty! The only imperfect thing about this LP is that it is far too short. But don’t let that fact deter you from experiencing the poetry of Desmond and Co. – if the album was half as long, it’d still be worth it.” The incisive review also notes:

"The teaming of Desmond and Gabor Szabo is a natural. Both have a subdued, liquid quality to their styles, which complement each other frighteningly well. Both solo with lyrical fire at low levels of volume, and both choose their notes elegantly and judiciously. Add a gracefully introspective pianist, a quality ‘second’ guitarist, and one of the three best bassists in jazz and the result is music uncluttered, complete in itself, and soulfully beautiful."

In this writer’s opinion, Skylark - in full or in part – is an artistic success that is nicely crafted by producer Creed Taylor and even more beautifully delivered by the musicians and soloists who made this possible. But, in the end, the album likely appealed only to fans of the saxophonist or the guitarist. (I was not able to verify how well the album performed.)

Fans of Desmond (and possibly Desmond himself) may not have been so accepting of Szabo, despite however magical their brief communion may have been. Skylark is, however, surely one of the best of the few records the Hungarian guitarist ever worked on as a sideman. The DownBeat review aptly concludes:

"Skylark happens to suit any mood you’re in, because it goes far beyond simple mood music, a label often slapped on both Desmond and Szabo in the past. By now we should be hip to the fact that intense doesn’t necessarily equal loud; but it’s hard for us to remember that in these days of Mahavishnu and Cobham. We need albums like Skylark to remind us."

Skylark was first issued on CD in 1988 with a “bonus track” recording of Victor Herbert and Al Dubin’s “Indian Summer” that had not appeared on the original LP. The piece is a quartet feature for Desmond with Gene Bertoncini (very much in Jim Hall mode), Ron Carter (who solos) and Jack DeJohnette. This warm, sunny waltz was probably recorded at the December session – and likely left off the original album because it calls attention to Szabo’s absence.

The slightly longer “alternate take” of “Indian Summer” – first issued as a “bonus track” on the 1997 CD release of Skylark - was, however, no doubt recorded first, as it features Gabor Szabo (who does not solo) supporting Desmond rather than Bertoncini. It is perfectly serviceable, particularly showcasing Szabo’s finesse as a fine accompaniment. It’s therefore a riddle as to how or why it was kept off the original release.

Like “Indian Summer (alt take),” the “alternate take” of “Music for a While” is also a quartet piece with Szabo in for Bertoncini. Again, Szabo doesn’t solo here. But the song’s first appearance came not on the 1988 CD release of Skylark but rather on the 1988 compilation CD Classics in Jazz. “Music for a While (alt take)” finally appeared on the 1997 CD release of Skylark - which was reissued as is in 2003 – and, to this day, remains the most comprehensive version of Skylark available to date.

Paul Desmond would record one more album for CTI – the straight quartet of Pure Desmond (1974), also with Ron Carter – while reuniting with Jim Hall for the guitarist’s landmark CTI debut Concierto (1975 – also arranged by Don Sebesky). The alto saxophonist died shortly thereafter of lung cancer on May 30, 1977. He was only 52 years old.

Likewise, Gabor Szabo recorded only one more record for the CTI subsidiary label Salvation, Macho (1975), which was produced and arranged by Bob James (the last of their collaborations together). After several more records on other labels, the guitarist died of liver and kidney failure in his native Hungary on February 26, 1982. He was only 45 years old.

Fortunately, as of this writing, Bob James, Ron Carter, Jack DeJohnette and Gene Bertoncini are all still with us and, happily, still working.

About the Cover: The arresting photograph on the cover of Skylark is so striking and unusual that it almost seems like an illustration – or, an illusion or a dream image. Its Zen quality suggests a flower made of hearts beating out waves of light.

The 1974 photograph, titled “Flower in Water,” is by the renowned photographer Pete Turner (1934-2017), the artist behind many of CTI’s iconic covers – notably the ironic icicles cover of Desmond’s 1969 album Summertime. Although the premise, noted in the photo’s title, is simple, the execution was a bit more of an experiment for the photographer than is widely known:

“I saw this flower floating in a man-made pool outdoors,” said Turner in his 2006 book The Color of Jazz, “and the sunlight was creating highlights on the water, like musical notes. A slow shutter speed can blur the image, but it can also blur the highlights while the black background stays the same. So I tried different shutter speeds and all the factors played in, like the wind, the movement of the flower, and the mystery of not knowing what it would look like till the film came back.”

The sense here is that “Flower in Water” taps nicely into Johnny Mercer’s lyric to “Skylark.” Certainly, the flower and its waves of light would appeal to the songbird of the title. But the “flower in water” also alludes to “a meadow in the mist / Where someone’s waiting to be kissed.”

Or, this: “a valley green with spring / Where my heart can go a-journeying.” Or, the wonderful verse that goes: ”And in your lonely flight / Haven’t you heard the music of the night? / Wonderful music, faint as the will o’ the wisp / Crazy as a loon / Sad as a gypsy serenading the moon.”

Saturday, October 28, 2023

John Scofield – “Uncle John’s Band” (2023)

Seemingly more music is released today than ever before. But precious little of this bounty rates more than a listen or two. Or, much of a mention. This is especially true in today’s seemingly fragmented jazz market. The young lions keep trying to rebrand the music: thus far to little avail. Meanwhile the old cats keep trying to keep up.

That’s why it’s notable when an album like guitarist John Scofield’s Uncle John’s Band comes along. This is a terrific record – and one that rates repeated listens. It’s familiar and exciting, like visiting with an old friend

The 71-year-old Scofield has made scores of interesting and enjoyable records throughout the years. Some, like Grace Under Pressure (1992); Hand Jive and I Can See Your House from Here (both 1994); Groove Elation! (1995), Quiet (1996); and A Go Go (1998) stand out. Most are considered classics.

So many others make for easy favorites, too; namely the Medeski Scofield Martin & Wood disc Out Louder (2007); the Gov’t Mule set Sco-Mule (2015); and the intoxicating brew that is DeJohnette / Grenadier / Medeski / Scofield’s Hudson (2017).

Uncle John’s Band is easily one of John Scofield’s very best discs. Mixing rock covers and jazz standards with Scofield’s clever and ever-incisive originals, this well-programed double-disc set breezes by without ever coasting or missing a beat. It holds one’s attention like too few discs these days do.

Accompanying the guitarist here are bassist Vicente Archer (Robert Glasper, Nicholas Payton, Jeremy Pelt) and long-time aide-de-camp Bill Stewart on drums. (Curiously, the package’s spine and label refer to this as the “John Scofield Trio” while the CD cover credits only the guitarist.) This trio first waxed Scofield’s Combo 66 for Verve in 2018 – an album I missed somehow.

This is the guitarist’s third outing for ECM Records – and the affiliation seems to suit the now elder statesman of the guitar. His earliest gig with the German label goes all the way back to Marc Johnson’s seminal 1986 outing Bass Desires (although Scofield had earlier appeared on a 1982 album by Peter Warren for the ECM-distributed JAPO label). Scofield has since appeared on other ECM albums by Johnson, Jack DeJohnette, Gary Burton and frequent Scofield collaborator Steve Swallow.

Scofield’s recent turn on ECM might recall another guitarist named John from Connecticut and fellow Berklee alum: John Abercrombie (1944-2017) recorded several dozen albums for ECM between 1975 and 2017. Interestingly, Scofield replaced Abercrombie in Billy Cobham’s band in 1975 and the two recorded the non-ECM album Solar together in 1984.

Among Abercrombie’s most memorable ECM discs were those he made with Gateway between 1976 and 1996, a trio featuring bassist Dave Holland and drummer Jack DeJohnette.

Like so many guitarists, Scofield shines brightest in a trio format – and this is an especially compelling trio of collaborators. Half of the set’s 14 tracks are Scofield originals. As ever, these are playful yet wistful, funky and folksy, yet welcoming and seemingly familiar. Here, though, Scofield’s signature turns of phrase breathe with an air of reflection, contemplation and, dare I suggest, a joie de vivre. This is a man who loves what he does.

Highlights among the originals include the blueish “Mo Green” (a money pun, perhaps, on The Godfather character), the Sco-meets-Wes groover “Mask,” “How Deep,” and “TV Band” (featuring a puckish quote of The Monkees’ “Last Train to Clarksville” – get it?).

The jazz standards are well selected, ranging from the familiar (“Stairway to the Stars” and “Somewhere”) to the too-little known (Miles Davis’ “Budo” and Dizzy Gillespie’s “Ray’s Idea” – while Scofield worked with both Davis and Gillespie, they likely never played these particular oldies).

But it may well be the rock covers that stand out most here.

Scofield opens the disc with a superb take on Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man.” He covers this one much like a sixties guitarist would, say Gabor Szabo circa 1967-68? (Surprisingly, Szabo never touched this one.) Scofield’s approach here nicely gives the twang of his guitar a sitar-like vibe.

The guitarist also delivers an ironic but surprisingly hip take on Neil Young’s “Old Man” and closes out the set with the inspired choice of the Grateful Dead’s 1970 hit (their first) that gives this album its name. Scofield makes meaty jazz out of this folksy bit of bluegrass, imbuing it with the sort of Americana that fellow guitarist Bill Frisell has long traversed. Scofield owns this one, though.

“Uncle John’s Band,” song and album, would make ideal fodder for a blindfold test. John Scofield is easily identified at every turn here – from his signature songs to the way he simply plays a tune (and it really is playing; there is never a sense of effort or obligation). Uncle John’s Band would even make the ordeal of wearing a blindfold seem joyful. Very highly recommended.

(In another anomaly, the ECM website lists the recording date of Uncle John’s Band as August 2022, while my copy of the disc lists the date as August 2023 – an especially quick turnaround for an October 2023 release.)

Thursday, September 21, 2023

Gabor Szabo – “Rambler” at 50

Early in his career, guitarist Gabor Szabo (1936-82) had the incredibly good fortune to be signed to Impulse Records, one of the most significant American jazz labels of the sixties. That came about mainly because of the successful contributions the guitarist made to Chico Hamilton’s critically and commercially successful records on the label in the early sixties – and producer Bob Thiele’s early championing of the guitarist.

The records waxed by Szabo on his own for Impulse, recorded between 1965 and 1967, were significant and remain among his best-known and some of the most important recordings of the guitarist’s ever-so brief career.

By the next decade, though, Szabo again found himself at one of that era’s most important – and successful – jazz labels: producer Creed Taylor’s legendary CTI Records. (It is worth remembering that Impulse was also the brainchild of Creed Taylor, although the producer was long gone at Impulse by the time Szabo came along.)

CTI made stars of arranger/keyboardists [Eumir] Deodato and Bob James, trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, saxophonists Grover Washington, Jr., Stanley Turrentine and Hank Crawford, guitarist George Benson and singer Esther Phillips. Creed Taylor’s label even helped revive the careers of such jazz greats as vibraphonist Milt Jackson, trumpeter Chet Baker and, notably, guitarist Jim Hall and saxophonist Paul Desmond.

But, somehow, Gabor Szabo fell between the cracks at CTI. The guitarist recorded a mere three albums for the label between 1972 and 1975 and made a notable guest appearance on saxophonist Paul Desmond’s superb CTI outing Skylark.

While Szabo’s CTI albums boast first-rate productions, high-class musicianship and some of the guitarist’s best studio work of the period, none made much of a dent in the musical psyche at the time, nor added anything of much significance to the guitarist’s legacy.

Oddly, the second of these, Rambler (1974), probably had the least impact of all.

When Gabor Szabo arrived at CTI in the early seventies, the label was faring particularly well. There was every reason to believe producer Creed Taylor could reignite the spark that made the guitarist’s magical touch so alluring earlier in his career.

It’s no secret that Gabor Szabo was floundering at this point in his career. After a brief run of unsuccessful records on the Blue Thumb label, the guitarist seemed to be struggling to find his place in a jazz world that CTI seemingly perfected.

His first album for the label, Mizrab, is a prototypical “CTI album,” with long, original groovers and CTI’s top-tier in-house talent. The first side of that record – featuring the songs “Mizrab” and “Thirteen” – also remains among Szabo’s best-ever recordings. Unfortunately, the album failed to make the waves it deserved.

For his CTI sequel, Gabor Szabo made a much more personal statement (recording with his own band at the time) but one that ironically feels much more anonymous. That is largely because Szabo turns the album over to his bass player, Wolfgang Melz, who wrote five of the album’s six songs.

The overall effect is that Gabor Szabo sounds like a guest on his own album.

Szabo’s quartet played Carnegie Hall on Friday, September 21, 1973, headlining a “Three Guitars” program that also featured John Fahey and Laurindo Almedia: “three guitarists who don’t appear very often in New York.” As John Rockwell reported in the New York Times:

Szabo also performed at Montclair High School in Montclair, New Jersey, on Friday, September 28 and Saturday, September 29, indicating that the bulk of this album was recorded between these two concert dates.

Remarkably, producer Creed Taylor allowed Gabor Szabo to record with the band he brought from California for the Carnegie Hall performance: keyboardist Mike Wofford, drummer Bob Morin and electric bassist and composer Wolfgang Melz. CTI’s in-house arranger Bob James – who, at this writing, just issued his latest CD, Jazz Hands - is credited with “musical supervision” and overdubs several keyboards of his own (an uncredited percussionist, probably Ralph MacDonald, is evident throughout as well).

Even more remarkably, Taylor allowed Szabo to hand off the album’s compositional duties to Melz. I have often wondered whether this was an act of defiance on Szabo’s part, similar to Miles Davis refusing to let Warner Bros. profit off the publication of his music. But Szabo retained the publishing rights of his own compositions on other CTI albums. Szabo was therefore either unprepared or unmotivated to provide originals for Rambler.

Born in Germany in 1938, Wolfgang Melz came to the U.S. in the early sixties – playing, of all things, the banjo. Almost immediately, Melz was playing Dixieland with Teddy Buckner and flat-out country music with Buck Owens. He discovered electric bass almost by accident and became obsessed with it. The self-taught Melz had neither previously played upright bass nor ever tried to play it throughout the remainder of his career. But he distinguished himself on the electric instrument almost immediately.

Melz got his professional start playing bass with jazz singer Anita O’Day and in the pop-rock group The Association. He quickly thereafter became a studio musician. Notably, of the few records he’s waxed, where he is actually named, most are all in the company of his studio friends.

Shortly thereafter, Melz met Szabo through keyboardist Richard Thompson, who was part of The Association when Melz was part of that group. Melz and Szabo hit it off right away (Melz has always quipped that Szabo said they were “born in the same hometown, Europe!”) and the bassist joined Szabo’s group – as did Thompson and vibraphonist Lynn Blessing (on whose sole solo album, Sunset Painter, Melz appeared).

Melz – known as “Wolfie” to friends and family – had previously written “Country Illusion” for Szabo’s 1970 album Magical Connection and would appear on the guitarist’s High Contrast (1971 – where he collaborated on that album’s dazzling “Fingers”) as well as Charles Lloyd’s terrifically underrated Waves (1972 – also with Szabo). The bassist appeared with Szabo (mainly on West Coast dates) for the next few years before retiring to Houston, Texas, where he still resides today.

”Rambler” had been in Szabo’s repertoire for several years by this point. The song, known then as “The Rambler,” was first recorded by Szabo in June 1970 as part of the Magical Connection sessions, but remains unreleased to this day. The song – more riff than melody, really – is an appealing bit of rock-funk that could have easily found favor in the Allman Brothers or even Three Dog Night.

Here, in the first thirty seconds, the guitarist and the bassist spar beautifully. Their communion casts a spell that emboldens the song and launches Szabo into one of his most compelling solos on the record. It’s easy to hear what appealed to the guitarist in this rock-ish groove: he’s clearly having fun here. But not everyone was as captivated by the charm of this piece as I am:

"Rambler," wrote critic Leonard Feather of a 1974 live performance of the tune, “[is] of no particular interest harmonically or structurally. Szabo, who at times has a tendency to extract an almost banjo-like tone from his guitar, didn't seem able to work up much concern for what he was doing—understandably, since the material itself [is] worthy only of a second-rate rock group.”

“Rambler” was also covered by then-San Francisco-based drummer Dick McGarvin for a 1974 album called Peaceful. McGarvin, a veteran of Paul Revere and the Raiders, a disc jockey and – probably – the actor who appeared in such films as Mommie Dearest (1981) and Diehard 2, recorded his take on “Rambler” several months before Szabo’s version came out, likely indicating he either heard the Szabo group perform it (in San Francisco) – or possibly performed it himself with Szabo.

The ballad “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye” is tailor-made for Szabo and his romantic sensibilities. While it is certainly molded in the “soft rock” of the day, there is a distinct hint here of European classicism, not dissimilar to the guitarist’s own later ballad “Time.” This “Goodbye” is sort of like a broken waltz.

Here, as on several occasions on Mizrab, Szabo subtly overdubs himself on guitar. Bob James offers a lovely piano solo that suggests a touch of Leon Russell’s “A Song for You” that propels Szabo into his own powerful, though plaintive, statement.

The breezy ”New Love” has the West Coast pop flavor of America or Seals & Crofts and, with half a century’s hindsight, sounds like a prototypical variation of smooth jazz. James offers another piano solo before the rhythm section (bolstered by Morin) kicks up the pace for the guitarist’s terrific solo flight. Szabo biographer Károly Libisch calls “New Love” a “beautifully crafted, inspired, delicate piece.”

“Reinhardt,” another of Melz’s rock-like vamps – this time, in distinctly Krautrock mode – is named not for Belgian jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt but rather the bassist’s son. (Melz, who has a brother named Reinhardt, also has a grandson with this name).

I don’t find this to be a particularly compelling or engaging tune, but, again, the rhythm section is all in and works up a head of steam to inspire Szabo toward some of his more interesting work here. But James is somehow allowed to overplay his hand on “Reinhardt,” adding odd synthesizer washes, unusual organ doodles and a mélange of distractions over a rather uninspired electric piano solo.

Almost exactly one year later, Szabo would include “Reinhardt” in the program of music he performed with Hungarian musicians for Hungary’s first-ever TV program devoted to jazz music: Jazzpódium 74: Szabó Gábor (USA) Müsora. While “Reinhardt” was not broadcast at the time, the performance was recorded and included on the 2008 LP/CD release Gabor Szabo In Budapest.

The delightful ”Help Me Build a Lifetime” is one of the album’s hidden gems. For some reason, this catchy little number never had much prominence inside – or outside – of Szabo’s orbit. “Lifetime” harks back to those wonderfully zippy tunes like “Cheetah,” “Sophisticated Wheels” or “Comin’ Back” that Szabo could whip out in his sleep. Indeed, Szabo (who overdubs himself again) delivers a fiery solo here that recalls those glorious early days. Melz himself offers up yet another tasty solo.

Robert Lamm’s pretty “All is Well” is an odd addition to the program. This little-known piece originated on the band Chicago’s 1972 album Chicago V. Lamm had already written such well-known Chicago hits as “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is,” “Twenty-Five or Six to Four” and “Saturday in the Park” (also on Chicago V). “All is Well” was not even released as a single by the group. One wonders whose idea it was to cover it here.

Szabo’s presence is almost perfunctory at this point. “All is Well” is seemingly more of a showcase for James’s piano – which has the strangely muffled resilience engineer Rudy Van Gelder accorded to all acoustic pianos he recorded for CTI during this period. The song’s outro offers its most compelling case, wherein the quartet is allowed to riff off the melody while the guitarist and bassist dance around each other’s lovely figures. A little more of this would have been magical.

Rambler, to these ears, is a satisfying, well-rounded program. But while the guitarist is in fine fettle throughout, the album is, however, only a middling success: neither the best he could do nor the worst he actually did.

One misses Szabo’s compositional contributions, yet Melz’s tunes – not to mention his adept work on bass – fit Szabo like a glove. And the guitarist’s enthusiasm for the program can hardly be questioned.

In some ways, Rambler, like High Contrast (1971) before it and certainly Faces (1976) later, is something of a transitional record: the result of a one-time maverick looking for a way to fit in to changing times and changing tastes. He was hardly alone there.

Szabo was off to California shortly thereafter for a scheduled appearance starting on Tuesday, October 2 at Howard Rumsey’s Concerts by the Sea in Redondo Beach. He’d be back on the East Coast in late November for sessions with saxophonist Paul Desmond that resulted in the marvelous album Skylark (more on that later).

Szabo’s second CTI album was released in March 1974, at the same time as vibraphonist Milt Jackson’s second CTI album, Goodbye. After much digging, I have been unable to determine whether the Szabo record ever charted or how much it might have sold.

”Szabo has abandoned his feedback sound,” wrote Billboard of Rambler, “and now concentrates on blending pure, beautiful tones within the constantly moving rhythmic feel of this quintet. There is a haunting, melodic quality to his playing, whether it's on the single note lines or when strumming several strings al the same time. Bassist Wolfgang Metz is a superb accompanist, duet partner with Szabo on guitar, laying down strong, rich notes.” (April 27, 1974)

DownBeat was far less charitable. In a two-and-a-half-star review (oddly peppered with typos), critic Jon Balleras griped, “The problem is partially with programming. Too many of these tunes fall into the same lightweight rock groove; while their melodies are listenable, they’re far from memorable….Melz’s bass work, though, is worth listening for…In short, this is pleasant music; you can probably dance to it, but I don’t recommend it for serious listening.” (July 18, 1974)

Surprisingly, there were no singles issued from the album, although at least one tune, “Help Me Build a Lifetime,” had a reasonable shot at radio airplay. “It’s So Hard to Say Goodbye” might have had a chance as well.

The Japanese label P.J.L. (Polystar Jazz Library) label licensed Rambler, among about a dozen other CTI titles including Szabo’s Macho, from King Records for a CD issue in 2002. Sony Records, which owns the bulk of the CTI catalog outside of Japan, has since included Rambler on most streaming services…so, it should be easy to hear the album in whatever media format you prefer.

About the Cover: The striking photograph on the cover of Rambler was shot in 1973 by Pete Turner inside the Hyatt Regency hotel in Houston, Texas. Opening the previous year, the hotel is famed as Houston’s tallest and prominently features a revolving restaurant called the “Spindletop.” The hotel was also the site for a scene in the 1976 film Logan’s Run.

“In this period,” noted photographer Pete Turner in his landmark book The Color of Jazz (2006), “when anything went for these covers, those atrium hotels were just coming in. It was a big visual turn-on for me. Up to that point, nobody photographed hotel lobbies. The lighted paths are actually elevator shafts. I tilted the camera and that’s what gives it a directional excitement. I used daylight colors to give it that warm effect.”

In a nice bit of kismet, it’s worth noting that Rambler bassist Wolfgang Melz himself ended up relocating to Houston, while Rambler keyboardist Mike Wofford was born in Texas…but miles away, in the lovely town of San Antonio, where I spent a brief sojourn myself.

While a hotel seems to be an ideal way to represent a rambler's plight - or - flight, Pete Turner's terrifically-stylized photograph beautifully suggests an architectural web. It begs the question: Who is the rambler, the spider or the fly?

Saturday, August 26, 2023

Gil Evans on Verve (1964-88)

Under the aegis of Creed Taylor, Verve Records may well have reached its commercial, critical and artistic zenith in 1964. Consider just some of the label’s releases that year.

There was not one but three great Jimmy Smith records issued in 1964, notably the exceptional Lalo Schifrin-arranged The Cat.

Also out that year were guitarist Wes Montgomery’s Verve debut, Movin’ Wes; Bill Evans’s evergreen Trio 64; and, of course, the multiple Grammy Award-winning Getz/Gilberto, the disc that recognized and rewarded saxophonist Stan Getz and guitar/vocalist João Gilberto, engineer, Phil Ramone, and the album’s huge hit single, “The Girl from Ipanema,” helmed by ingenue Astrud Gilberto.

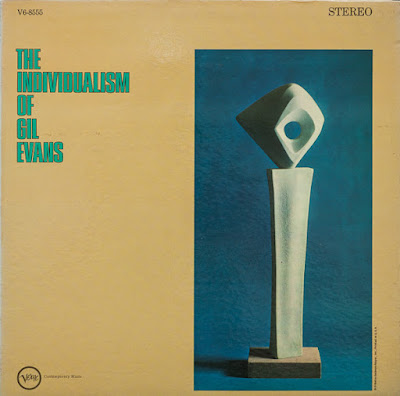

And then there was The Individualism of Gil Evans, the exceptional Verve debut of the great arranger, then-reluctant bandleader and pianist Gil Evans (1912-88).

The album was Evans’s first foray under his own name since the magnificent Out of the Cool four years earlier, an album also produced by Creed Taylor. (That album’s sequel, Into the Hot [1961], was a Gil Evans outing in name only.) In the meantime, Evans was actively working with Miles Davis on the trumpeter’s celebrated Miles Davis at Carnegie Hall (1962) and the troubled but still worthy Quiet Nights (1963).

While Evans effectively recorded only one album for Verve, the majority of his studio work for the remainder of the decade was with the label and yielded several discs well worth exploring. (Evans’s work with Miles Davis in 1968 and an eponymous disc some two years later, for the briefly-lived Ampex label, later retitled Blues in Orbit, are not part of this conversation.)

Gil Evans - "The Individualism of Gil Evans" (1964)

Recorded over four sessions between September 1963 and July 1964, the five songs that make up the original LP of The Individualism of Gil Evans seem to chronicle a desire for some sort of perfection that likely frustrated producer Creed Taylor, himself a perfectionist. It’s probably the same sort of thing that flummoxed Evans and Davis on what Columbia put out as Quiet Nights.

But if the result is imperfect, The Individualism of Gil Evans comes as close as you can get to a perfectly satisfying musical statement from Gil Evans.

This exquisite album is probably best known for its signature piece, “Las Vegas Tango.” Named because “it had a kind of open sound like the plains,” “Las Vegas Tango” is a brilliant two-part invention: the early part gets a mournful solo by trombonist Jimmy Cleveland while the brassy part (which screams of the Las Vegas strip to these ears) benefits by guitarist Kenny Burrell, almost buried in the mix.

It’s easy to miss the significance of Paul Chamber’s moody bass and Elvin Jones’s aggressive percussion on “Las Vegas Tango”’s affective and hypnotic draw. But it’s their work that helps makes this track as singular and memorable as it is.

Unlike other songs present here, Evans never performed “Las Vegas Tango” again – until bandleader and Evans biographer Laurent Cugny persuaded the song’s composer to revive it during a European tour at the end of his life. “Las Vegas Tango” is hardly the standard it should be. But it has been effectively covered by artists as diverse as Robert Wyatt, Michael Shrieve, Nels Cline, Mike Gibbs and, most notably and effectively by Gary Burton.

“The Barbara Song” (a.k.a. “Barbarasong”) is a haunting theme taken from Kurt Weill’s music for Bertolt Brecht’s “play with music” The Threepenny Opera. The song has not often received much coverage in jazz, but it was notably covered in 1962 on a Weill tribute album by Andre Previn and J.J. Johnson. Here, Evans crafts some gorgeous, dreamlike horn swaths while offering his always welcome “arranger’s piano.” Wayne Shorter takes a beautifully lyrical solo that is particularly notable as that aspect of his playing hadn’t been much in evidence at the time.

“Hotel Me” is one of the themes Evans and Miles Davis wrote for the play “Time of the Barracudas” (more on that later). If this one is a bawdy stripper-type theme, it is certainly one of the classiest. Evans balances low brass with wispy flutes and takes a number of solo spins on piano, playing – as he himself says in the album’s liner notes – “real broad.” Evans continued performing “Hotel Me” throughout the remainder of his life, but the song was also known as “Jelly Rolls” by the early seventies.

In such company, the likeable but ever-so brief ”Flute Song,” a feature for Al Block, and “El Toreador” (spotlighting trumpeter Johnny Coles) feel more like filler than fleshed-out melodies. Both are far too fleeting but impressionistic and ever-Evanescent orchestral pieces that serve more as transitions than compositions – or, like outtakes from the Davis-Evans masterwork Sketches of Spain (1960).

The Individualism of Gil Evans was released in September 1964 to mostly favorable fanfare. "’Exotic Jazz,’" wrote Billboard on September 26, 1964, “truly special, highly stylized and individualistic to the last note.”

”The 88'er's thematic originality and inventive instrumentation,” wrote Cash Box, somewhat condescendingly, “is evident throughout these highly individual performances” (also September 26, 1964). Notice how both reviews use the album’s title as a point of contention, making it difficult to discern whether individuality was considered a good thing or bad.

Individuality doesn’t normally sell records. But it leaves a mark, as this record surely did. From its striking cover to the amazing music within, this album continues to speak volumes.

The Individuality of Gil Evans was nominated for a Grammy Award as Best Instrumental Jazz Performance – Large Group or Soloist with Large Group. While the Miles Davis-Gil Evans set Quiet Nights was also nominated that year, both lost to guitarist Laurindo Almedia’s lovely but long-forgotten Guitar from Ipanema.

Kenny Burrell - "Guitar Forms" (1965)

The prodigiously adaptable, prolifically recorded and always engaging guitarist Kenny Burrell had previously factored in orchestras accompanying such singers as Billie Holiday, Jimmy Witherspoon, Dinah Washington and Tony Bennett.

He was also one of Creed Taylor’s go-to session guys, appearing on Verve records by Kai Winding, Johnny Hodges, Cal Tjader and, notably, Jimmy Smith. Burrell was also one of the key contributors to the aforementioned The Individualism of Gil Evans.

After a long series of albums under his own name – mostly, but not solely, for the Prestige label – Kenny Burrell was offered an opportunity by Verve producer Creed Taylor to record an album arranged and conducted by the one and only Gil Evans. What musician worth his (or her) salt could turn down such an offer? Of course, Kenny Burrell agreed.

That album, Guitar Forms, is only sporadically orchestral – and notably subtle when it is. But it is a bravura showcase of Kenny Burrell’s acuity, vast gifts and ever-enduring appeal.

The nine tracks appearing on the original LP were recorded over four sessions, two in December 1964 (with Gil Evans and an orchestra) and two in April 1965 (in a small-group setting – audibly without Evans and company). While it is not known whether the arranger was meant to preside over the entire album, the mix of orchestral and small group suits the leader just fine. Indeed, the small-group pieces hold their own among the orchestral pieces and do much to showcase Burrell’s musicality and versatility.

The album comes out swinging with Burrell in familiar territory, vamping on Elvin Jones’s absolutely Burrell-like “Downstairs.” Burrell is equally in his element on bassist Joe Benjamin’s “Terrace Theme” and the guitarist’s bossa-noverdrive number “Breadwinner,” all in a quintet with pianist Roger Kellaway, Benjamin on bass, Grady Tate on drums and Willie Rodriguez on congas.

The guitarist himself transcribed George Gershwin’s 1926 piece “Prelude #2” for solo acoustic guitar. It’s a particularly lovely, though brief, performance. The liner notes tell us that there was not enough space on the original album for the entire performance, so the recording was edited to offer up an “excerpt.” Strangely, though, when the disc was reissued on CD in 1997 with multiple takes of “Downstairs,” “Terrace Theme” and “Breadwinner,” there was no sign of an extended take of “Prelude #2” to be found.

As nicely balanced as this set is, the focus here is on the pieces Burrell performs with Gil Evans’s orchestra. Behind the scenes on these tracks are such luminaries as longtime Evans associates trumpeter Johnny Coles, trombonist Jimmy Cleveland and saxophonists Lee Konitz and Steve Lacy as well as such significant aides-de-camp as Richie Kamuca, Ron Carter and Elvin Jones.

None stand out as soloists here. But each serves Evans’s end to make his featured soloist sound, well, magnificent. The result is that Guitar Forms is as much a pleasure for fans of Kenny Burrell as Gil Evans. The five tracks covered here are the only five tracks listed in the recording logs. One could hope for more…but, well, dreams are just dreams.

First up is “Lotus Land.” Written in 1905 by British composer Cyrill Scott (1879-1970), “Louts Land” is clearly inspired by Asian harmonies, giving it an overtly exotic appeal. It is probably Scott’s best-known composition and its popularity is likely due to Martin Denny, who covered the tune on his 1957 “bachelor pad” classic, Exotica.

While pianist George Shearing covered “Lotus Land” in 1964, Kenny Burrell’s first brush with the song likely came during the September 1964 session he waxed for little-known pianist Eddie Bonnemère’s sole Prestige album Jazz Orient-ed.

Here, Burrell and Evans take “Lotus Land” outside of its Asian framing to more of a Spanish setting, obviously recalling Sketches of Spain. It’s an inspired reconsideration. Burrell takes the lead on acoustic guitar, while Evans propels with subtle flute and low-brass motifs. Burrell’s solo here always reminds me of the Flamenco piece played at the outset of John Barry’s Goldfinger (1964) score. But even at nine-plus minutes, this piece seems to fade as something more promising was yet to come.

Alex Wilder’s “Moon and Sand” (1941) is a haunting ballad that hadn’t had much coverage in jazz in the mid-sixties. By the time Keith Jarrett recorded it in 1985, it was considered a “standard” and has since had much coverage, particularly among pianists.

Burrell had recorded the tune two months earlier with vocalist Pat Bowie on her Prestige album Out of Sight!, which is likely what gave the guitarist the idea to cover it here.

Burrell is on acoustic guitar while Evans provides a compelling bossa-nova framework, punctuated with impressionistic horn swaths. It’s a superb performance but producer Creed Taylor oddly brings the percussionists high up in the mix – suggesting some particularly aggressive waves washing up on those otherwise lovely shores.

Likely the inspiration behind Rudolph Legname’s Grammy-nominated cover photo, “Moon and Sand” stayed in the guitarist’s repertoire for many years. Indeed, Burrell recorded the song again in 1979 in a quartet setting – and with far more subtle percussion – for a lovely album called, what else, Moon and Sand.

Burrell’s “Loie” – written for his then-wife Dolores – originated on tenor saxophonist Ike Quebec’s 1962 Blue Note album Bossa Nova Soul Samba. Burrell also recorded a quartet version of “Loie” under his own name for Blue Note in 1963. That recording first appeared on a Japanese album called Freedom - issued in 1979 and reissued domestically on vinyl in 2011. That version of “Loie” can, however, be heard much more easily on the Blue Note compilation The Best of Kenny Burrell.

Here, again, Burrell beautifully leads on his acoustic axe. But Evans adds a fascinating sense of unease with oboe and some especially dramatic horn punctuations. There is, in this reading, an intriguing element of provocation: a love song gone awry. What could have been a jukebox jammer is, at least here, a tempest in a teapot. But it’s all the better for it.

Kenny Burrell had recorded “Greensleeves” with Coleman Hawkins in 1958 and Leo Wright in 1962, but the song was best known in jazz – then and now – from the John Coltrane Quartet’s bravura performance of the tune on the Creed Taylor-produced album Africa/Brass (1961).

The guitarist introduces “Greensleeves” on solo acoustic guitar before the orchestra rolls in and launches Burrell into his electric and positively electrical feature. Evans provides some of his finest big-band charts here since his Claude Thornhill days – while even foreshadowing the baroque charts Don Sebesky and others would provide to jazz players in the years to come.

Burrell would go on to record “Greensleeves” in trios with Jimmy Smith on the memorable Organ Grinder Swing (1965) and live on the otherwise forgotten Jazz Wave, Ltd: On Tour (1969).

Harold Arlen’s 1935 ballad “Last Night When We Were Young” is, perhaps, the album’s sleeper. The tune practically goes by without notice. It was a staple for Judy Garland, Tony Bennett and, perhaps most notably, Frank Sinatra. Burrell has long covered Arlen: “Get Happy,” for example, as well as “Out of this World,” “A Sleepin’ Bee,” “Blues in the Night,” “As Long as I Live” and “One for My Baby,” among others.

”Last Night” features some of Evans’s most subtle orchestrations. Indeed, they’re nearly negligible given Burrell’s acoustic performance of the tune. Evans’s contributions here are brief – but exceedingly memorable. He does what any good arranger is supposed to do: step back and make the leader sound good.

Guitar Forms was released in October 1965 with one single issued from the album, “Loie” backed with the Evans-less “Downstairs.” The disc was first issued on CD in 1985 (which is when I first heard it) and again in 1997 with four additional takes of “Downstairs” and “Breadwinner” and three additional takes of “Terrace Theme,” but nothing extra from the sessions with Evans.

The album was nominated for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance – Large Group or Soloist with Large Group – losing to Duke’s Ellington ‘66 – while Gil Evans’s arrangement of “Greensleeves” was nominated for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist or Instrumentalist – losing to Gordon Jenkins’s arrangement of Frank Sinatra’s “It Was a Very Good Year.”

Guitar Forms is jazz at its classiest. The album stands out in Kenny Burrell’s extensive seventy-year discography as one of his best – which is saying something, given the sheer amount of good guitaring the man has waxed over that amazing amount of time. It is also ranks, to these ears, among the highlights of Gil Evans’s distinguished discography.

Burrell would go on to wax “arranged” albums with such greats as Richard Evans, Don Sebesky, Johnny Pate, Benny Golson and, much later, Gerald Wilson. But nothing comes close to the singular achievement that is Guitar Forms.

Astrud Gilberto - "Look to the Rainbow" (1966)

The idea of pairing Brazilian vocalist Astrud Gilberto with jazz arranger Gil Evans seems, if not necessarily inspired, then certainly audacious. Producer Creed Taylor, the only one who could have made such a meeting possible in the first place, likely regretted the decision almost immediately.

Recorded over no less than five sessions in November and December 1965 and one in February 1966 – and requiring two additional arrangements by Al Cohn (“Lugar Bonita” and “El Preciso Aprender A Ser So”) – the eleven songs that make up what became Look to the Rainbow must have felt like pulling teeth.

Listening to the result sometimes feels like no less than a trip to the dentist’s office itself: sometimes pleasant, sometimes not.

Surprisingly, there is almost no chemistry here. Gilberto, who is often said to inject “a certain sadness” in her singing, sounds positively disinterested here. She is surely not the breezy “Girl from Ipanema” (which she isn’t anyway) on this disc. Gilberto sounds bored, sometimes off-key, not to mention uninspired and even confused by her accompaniment. Such confusion seems justified.

To be fair, Astrud Gilberto, despite her stunning ability to sing in many languages, is not a jazz singer. And while Gil Evans had arranged for several singers earlier in his career (Helen Merrill, Marcy Lutes, Lucy Reed), his affinity for this sort of music was limited…at best.

Let’s face it: Astrud Gilberto is no jazz singer and Gil Evans is no populist.

It is notable that only two musicians are credited here. That’s pretty unusual for an Evans project and suggests that his (or somebody’s) heart really wasn’t in it. Not even the Stan Getz-ish soloist on “Maria Quiet” is identified.

The Verve recording logs list the possible participation of Johnny Coles on trumpet, Bob Brookmeyer on trombone and Kenny Burrell on guitar. Evans himself is credited on piano and while it sounds like him on the album’s tinkly title track, the soloist on “Bim Bom” surely does not. Grady Tate is audibly present throughout on drums.

Baden Powell’s “Berimbau” kicks the album off in fine style, offering the best of both singer and arranger the disc has to offer. It promises much more than Look to the Rainbow ends up delivering. Featured on the titular instrument is Brazilian percussionist Dom Um Romão, who played drums on the 1964 version of the song by Trio 3D on their album Tema 3D.

The album’s first two English-language songs are both Michel Legrand numbers, “Once Upon a Summertime” (a.k.a. “La valse des lilas”), which Evans previously tackled with Miles Davis on Quiet Nights, and the soporific “I Will Wait for You,” with a brief statement of sorts from trumpeter Johnny Coles.

Antonio Carlos Jobim’s well-known “(A) Felicidade” and ”Frevo” – both from Black Orpheus (1959) – get fairly uncomfortable makeovers in Evans’s hands. The latter tune, especially, gets a wildly incongruent Carnival setting. It’s as though John Barry went native much as he did for the Junkanoo sequence in Thunderball.

The pair don’t really get back on track until the album’s closer, an English-language cover of Jobim’s “She’s a Carioca.” This iteration of the song made its first appearance on the 1965 Nelson Riddle-arranged album The Wonderful World of Antonio Carlos Jobim (which also included Dom Um Romão on drums), although Gilberto leaves out all the bits about being “in love with her in the most exciting way.”

Even Evans is back in his element here. His horn parts – which don’t even attempt to mimic Riddle’s smoother strings and flutes – are more in his signature style and fit the song and Gilberto’s style more seamlessly than elsewhere.

Gilberto avails herself nicely on the Brazilian pieces – perhaps because she had more of a hand in selecting them. These include the aforementioned “She’s a Carioca”; “Bim Bom,” written by ex-husband João Gilberto (and previously covered by Stan Getz and Gary McFarland on Big Band Bossa Nova); and Carlos Lyra’s spunky “Maria Quiet” (first heard in America on a 1965 Sergio Mendes record), which gets a set of English lyrics by Norman Gimbel specifically for this recording.

Look to the Rainbow was released in April 1966 to surprisingly little fanfare. “The clear, bell-like tones that mark Miss Gilberto's vocal style,” wrote Billboard, “enhance the jazz-oriented melodies arranged by Gil Evans…Should prove a hot sales and programming item.” But it didn’t.

Oddly, there were no singles issued from the album at the time. Instead, Verve had Astrud Gilberto front some contemporaneous movie themes: the non-album, Don Sebesky-arranged “Wish Me a Rainbow” (from This Property is Condemned) and, later in the year, “Who Needs Forever” (from the soundtrack to The Deadly Affair).

In July of the following year, Verve released a promotional five-disc boxset of singles titled Verve Celebrity Scene – Astrud Gilberto that sampled ten songs from Gilberto’s catalog, including this album’s “Once Upon a Summertime,” “Berimbau,” “Look to the Rainbow” and “Lugar Bonita.” The package, issued to radio stations for airplay, likely had very little effect.

After Look to the Rainbow, Astrud Gilberto would team with fellow Brazilian ex-pat Walter Wanderley for A Certain Smile A Certain Sadness (1967). (The first side of that LP appears as “bonus tracks” to the first CD issue of Look to the Rainbow.)

Gil Evans would again vanish from the scene. “Periodically,” wrote Ralph J. Gleason, “since he first attracted attention in the jazz world, Gil Evans has made a statement and retreated from the stage into a kind of musical hibernation into which he assimilates music and lets it work its way through his system. Then he emerges again with some new contribution.”

That contribution would not appear until four years later with a newly electric Evans set on Ampex called, simply enough, Gil Evans (later known as Blues in Orbit). That album laid the foundation of the orchestra that would personify Evans for the remainder of his career.

Gil Evans Orch, Kenny Burrell & Phil Woods - "Previously Unreleased Recordings" (1974)

The January 1974 release of this record greatly upset Gil Evans. He considered these outtakes from The Individualism of Gil Evans as unfinished, inferior or unacceptable to the work that was issued in 1964.

This disc was one of Verve’s “Previously Unreleased Recordings,” a series that rescued six otherwise unissued treasures buried in the Verve vaults by Stan Getz and Bill Evans, Johnny Hodges with Lalo Schifrin, Clark Terry with Bob Brookmeyer, Jimmy Witherspoon with Ben Webster and Sonny Stitt. The majority of these were originally produced by Creed Taylor, who, in 1974, was basking in the success of his own CTI Records productions. Taylor was likely unhappy about these releases as well.

The Evans set contained five previously unissued tracks Evans waxed over three 1964 recording sessions: March 4 (“Blues and Orbit,” “Isabel”), May 25 (“Concorde,” “Spoonful”) and July 9 (“Barracuda” – the same session that yielded the previously-released “The Barbara Song”).

Perhaps what galled Evans even more is the shoddy way the music was treated here. The titles “Blues in Orbit” and “Isabel” (also listed on a British compilation as “The Underdog”) are both incorrectly titled and credited. “Blues in Orbit,” a song properly credited to George Russell, is actually Charlie Parker’s “Cheryl” while “Isabel” is Al Cohn’s “Ah, Moore.”

It’s difficult to say how these songs ended up with these titles. But they were likely listed as such on the original 1964 recording logs. But since the recordings weren’t released at the time, nobody bothered to correct the sheets. Whoever was in charge of putting these recordings out in 1974 just didn’t know enough to correct the titles – or ask someone who might have known, like, say, Mr. Evans.

Both these tunes are from a quartet session that featured Evans on piano, Tony Studd on bass-trombone, Paul Chambers on bass and Clifford Jarvis on drums. Neither is particularly bad nor shames anyone in any way. Each spotlights Studd (sounding very much like Bob Brookmeyer here) and, unusually, Evans on piano – very nicely.

But there is a jam session quality to these two pieces, as though the players were just warming up or winding down from the real work at hand. Neither piece would have fit comfortably in or on the large-group soundscapes of The Individualism of Gil Evans. Both producer Creed Taylor and the record’s leader would have understood this and objected to the release of these tracks – in 1964 and 1974.

John Lewis’s ”Concorde” and Willie Dixon’s “Spoonful” (on the record label as “Spoonfull”) come from a session that also included a piece titled “Punjab,” a track that was never finished to Evans’s satisfaction – and, remarkably, has never been issued (although bandleader Ryan Truesdell recorded Evans’s arrangement of “Punjab” for the 2012 disc Centennial).

While “Spoonful” might have come as a surprise to listeners in 1964 – maybe even 1974, too – one listen reveals just how flawlessly Evans can bring any good tune into his own musical universe (something which failed him somewhat on Gil Evans Plays the Music of Jimi Hendrix, also released in 1974). Evans’s horn voicings here are ethereal.

As it turns out, it would be another 14 years before anyone would know how savagely “Spoonful” was edited here. The nearly 14-minute piece lost about four and a half minutes of playing time for this release, sacrificing Thad Jones’s terrific solo, a piano interlude and a good bit of that sensuous Evans orchestration. Other soloists heard here are Kenny Burrell, Phil Woods and, intermittently, Evans himself.

Rounding out the record is “Barracuda,” perhaps this disc’s most notable piece. If this was left off The Individualism for time considerations, it suggests that either Evans or Taylor were hoping for a follow-up. It’s just too good to sit in a vault somewhere.

“Barracuda” – credited here solely to Evans – is an extended version of one of the cues Gil Evans and Miles Davis crafted for Peter Barnes’s 1963 play Time of the Barracudas. Davis and Evans wrote and recorded a series of twenty-some cues, including this one and “Hotel Me,” in October 1963 that amounted to about 12 minutes of music. A tape recording of the score was meant to accompany the play’s performances, but it’s uncertain whether that ever happened.

The Miles Davis recording of the suite wouldn’t see the light of day until the 1996 box set Miles Davis & Gil Evans – The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings and, then, as a bonus track to the 1997 CD issue of Quiet Nights.

Here, Evans elongates the theme as a feature for Wayne Shorter on tenor sax, Kenny Burrell on guitar and, notably, Elvin Jones on drums (props to Gary Peacock for his work on bass here, too). This must have been a revelation in 1974. It certainly was for this listener in 1988.

Wayne Shorter, who was present on the Miles Davis recording of the tune, also recorded the song in 1965 as “Barracudas” (credited there solely to Evans). But even that recording wasn’t issued until years later on the Japanese album The Collector (1979) and, in America, on the Etcetera LP in 1980 and on CD (with a different cover) in 1995.

Evans himself later recorded the song as “General Assembly” on his 1970 album Gil Evans (a.k.a. Blues in Orbit) and when “Barracuda” appeared on the 1988 CD release of The Individualism of Gil Evans, it was nicely placed at the beginning of the disc and was listed as “Time of the Barracudas.” In both cases, the song was properly credited to both Gil Evans and Miles Davis.

Gil Evans - "The Individualism of Gil Evans" (1988)

Coming mere months after Gil Evans’s death at age 75, this first-ever appearance of The Individualism of Gil Evans on CD seemed then like some sort of solace: a measure of the man’s craft and evidence of his singular genius. Surely one of Evans’s finest musical documents, this iteration of The Individualism remains, perhaps, the most complete and satisfying version of the disc that could be.

It’s also exactly what Evans himself wanted. The producers – who include the reliably thorough, careful and artful Michael Cuscuna and Richard Seidel with the assistance of venerable researcher Phil Schaap – worked closely with Evans himself in crafting the final presentation.

The CD doubles the LP’s original playing time by adding to the album’s original five titles (tracks 2 to 5), three titles appearing on the 1974 album (tracks 1, 8 and 9 – the newly presented unedited 13-and-a-half-minute version of “Spoonful”) and two previously unissued titles.

According to Cuscuna’s liner notes (which accompany Gene Lees’s original notes with Evans’s commentary), Evans was energized by hearing this recording of “Spoonful.” “Upon hearing the full version for approval of this CD,” writes Cuscuna, “Gil fell in love with the arrangement and the performance. He has resolved to bring it into the book of his current performance.”

As no official recording has documented such evidence, you have to wonder whether this ever happened.

In a bit of perfect programming, the CD opens not with “The Barbara Song,” as on the original LP, but with “Time of the Barracudas,” which was known on the 1974 album as “Barracuda.” This Evans original perfectly sets the stage for what else is to come. It’s mind-boggling that this treasure wasn’t issued at the time.

Perhaps another Evans album on Verve was in the works. That would explain the appearance here of the two previously unreleased titles, “Proclamation” and “Nothing Like You.” Both were recorded at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio on October 29, 1964, a full month after the original release of The Individualization of Gil Evans.

”Proclamation” is an impressionistic string of arpeggios that gets equally dreamy solos by Wayne Shorter, (possibly and briefly) Johnny Coles and Evans’s spiky piano motifs. Like “Time of the Barracudas” – known then as “General Assembly” – Evans would revisit “Proclamation” on his eponymous 1969 recording, later known as Blues in Orbit. There, it is briefer and much more dramatic: more nightmare than this disc’s dream scenario.

Bob Dorough’s “Nothing Like You” had been arranged by Evans in 1962 for Miles Davis (although the song was recorded during the Quiet Nights sessions, it wasn’t issued until 1967, where it was tacked on to the end of Davis’s otherwise quintet recording of Sorcerer). Here, the song is helmed by Wayne Shorter, who was also present on the Davis recording – a full two years before he joined the trumpeter’s now-famed second quintet.

This iteration of “Nothing Like You” removes Willie Bobo’s percussion in favor of (probably) Elvin Jones’s more aggressive drum work and adds (likely Kenny Burrell’s) guitar, flute and tuba to the soundscape. It also reminds listeners that Miles was merely part of the section on the original, not the soloist: surely a tribute to the gorgeous charts that Evans provided to him.

After this October 1964 session, Evans would work on several Verve sessions for Kenny Burrell and Astrud Gilberto. But the man largely vanished from the music scene after that. There was no full-fledged sequel to The Individualization of Gil Evans. By early 1967, producer Creed Taylor would leave Verve. He and Evans would never work together again.

Evans would reunite with Miles Davis in early 1968 for several takes of “Falling Water” and did not return on record under his own name until 1969 – and, oddly, on the then new and fledgling Ampex label.

Whether its title is complimentary or critical (or, knowing Creed Taylor, a bit of both), The Individualism of Gil Evans is an individual achievement and, in this presentation, among Gil Evans’s best work of the sixties, if not among the best work under his own name in his entire career.

Sunday, August 06, 2023

The Forgotten Fusions of Freddie Hubbard (1981-89)

Fusion jazz was as good as dead by 1980. Well, maybe not dead – but definitely not as cool or cutting-edge as it was only a decade before. It was also no longer the “fusion” of jazz, rock and funk it once was. At the turn of the eighties, fusion was much more informed by disco, itself a victim of popular – and, not-so-arguably, racist and homophobic – backlash by then.

For all the jazz players mining fusion throughout the seventies, many of whom became stars during this period, most saw the writing on the wall. The times were changing…yet again. Fusion players began to splinter off: some going back (awkwardly and inconsequentially) to their acoustic roots while others swam easily into the warm waters of “smooth jazz.” Some soldiered on, wherever it took them.

Consider trumpeter and flugelhorn player Freddie Hubbard (1938-2008). He easily and successfully traversed the worlds of bebop, post-bop, modal, free (“new thing”) and soul jazz in the sixties before launching into fusion at CTI in the seventies, beginning with his landmark album Red Clay (1970).

Shortly after winning a Grammy Award for his 1971 album First Light, the trumpeter left CTI for a highly lucrative contract (that CTI could not afford to match) at the mega-major Columbia label, home to fusion legends Weather Report, Herbie Hancock, John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra and (later) Chick Corea’s Return to Forever.

Oh, and someone named Miles – a frequent challenger to Freddie Hubbard in the polls and the charts throughout the years.

Between 1974 and 1980, Hubbard waxed seven studio records for Columbia, including his most divisive album (and a favorite of this writer), Windjammer (1976). Produced and arranged by Hubbard’s fellow CTI All Star alum Bob James, Windjammer became – and remains – Freddie Hubbard’s best-selling and highest-charting album, reaching #85 in the Billboard Top 200 in 1976.

The last Freddie Hubbard album to even crack the Billboard Top 200 – on Columbia or any label – was the superb 1978 Super Blue, essentially a CTI All Stars reunion. Hubbard’s particularly fine, but regrettably-titled Skagly (1980) made a minor dent on jazz radio. But even jazz radio stations were starting to vanish around the country by then.

In October 1980, Columbia “dropped” Freddie Hubbard (as well as Stan Getz and Wilbert Longmire) from the label – a mere five months after the release of Skagly, despite the album reaching number 14 that year on the Billboard Jazz chart. Apparently, that wasn’t good enough.

Oddly, though, Hubbard blamed his lack of success at Columbia on Bob James, of all people.

”I think Columbia relied too much on Bob James to produce jazz artists,” Hubbard told DownBeat in November 1981. “He wasn’t really a jazz producer. He was trying to get me away from jazz, which he did. Bob would just come in and lay down the tracks. I had to fit into what he had laid out. That was a mistake ‘cause there was no looseness.”

Outside of Windjammer, though, James had no known input on any other Hubbard album. It’s also unlikely James would have had the time for Hubbard after their lone album together as James was engaged with setting up his own Tappan Zee label and its artist roster – one that did not include the trumpeter in any way. But at least Hubbard himself considered Windjammer “a pretty good album.”

If Hubbard seemed bitter, his departure from Columbia freed him from whatever burdens Columbia imposed upon him---to do the exact same thing. While he was now a free agent, able to chart the waters of a new decade of ever-evolving tastes, technology and up-and-coming talent (notably a young lion named Wynton) he kept putting out more commercially-oriented fare. For a while, at least.

Now something of an elder stateman, Hubbard, only in his early forties, was busier than ever. He had a strong repertoire of originals and standards and was consistently able to keep a working band together. Hubbard did gigs on both the West and East Coasts, played festival dates all over the world and was often a featured soloist with many college bands.

A lot of these live dates were recorded and quite a few were issued during this period, most with Hubbard’s own consent. Hubbard also took advantage of many recording opportunities for a variety of American, European and Japanese labels.

Even though Hubbard was already part of one of the seventies’ only notable acoustic jazz groups, V.S.O.P. The Quintet (1976-79), he gradually returned to straight-ahead, or, as some would say, “traditional” jazz settings on his own.

The most memorable of these include the none too subtly-titled Back to Birdland (1981 – notable at the time for being digitally recorded), the all-star The Griffith Park Collection (1982), the terrific Sweet Return (1983) and the exceptional Double Take (1985), with Woody Shaw. Not for nothing are these Freddie Hubbard discs his best-remembered from the period.

Later in the decade, Hubbard would also take star turns on better-than-fine acoustic dates co-led by Benny Golson (1987), Kirk Lightsey (1988) and Art Blakey (1989) – all, notably, for labels outside of the U.S.

Still, he kept coming back to fusion. But the subject found Hubbard flip-flopping, as though the next one would be on his terms and the previous ones were on someone else’s terms.

“Everyone thought I was going after the money,” he said. “I’m the type of cat that likes to venture into all kinds of music.” But then he’d continue along these lines: “I know McCoy [Tyner] and Cecil [Taylor] have stuck straight on out with their thing, but my lifestyle is different. I wanna live good.”

While Hubbard hardly cranked out obvious Red Clay (1970) copycats, he did attempt to replicate First Light (1971) a bit more often than the market was willing to bear. Many contemporaneous critics were hostile toward most CTI records. But Hubbard’s CTI releases were held up as the trumpeter’s best recordings, particularly compared to his Columbia discs and these later fusion records.

Freddie Hubbard, whose sense of the market at the dawn of the eighties was probably not as sharp or as attuned as so many of his previous collaborators (consider, say, “Rockit”), he still waxed several albums of worthy music, nominally considered fusion music:

Mistral (1981), Splash (1981), Ride Like The Wind (1982), Life Flight (1987) and Times Are Changing (1989).

Without exception, each of these records – covered in the following posts – have at least one or more notable Freddie moments that are well worth cherishing and a perfect fit in “Hubbard’s Cupboard.”

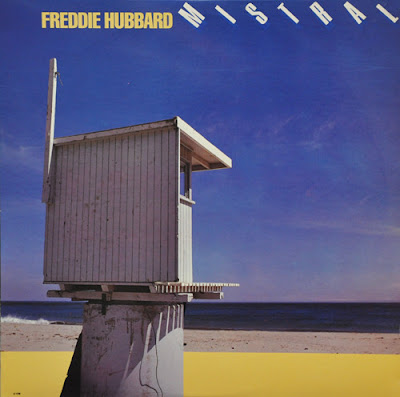

Freddie Hubbard – "Mistral" (1981)

Mistral probably derives its title from the cold winterly wind that blew Freddie Hubbard from his major-label perch at Columbia. Recorded over several days in September 1980, Mistral was likely recorded for – and financed by – the Columbia label. The recording was picked up and released a year later by the Japanese East World label and issued in the U.S. by Liberty, home at the time to guitarist Earl Klugh.

Curiously, though, the record is purportedly produced by John Koenig, then head honcho at his father Lester’s revived Contemporary Records. Koenig was responsible for producing the trumpeter’s guest appearances on two terrific records of the period: pianist George Cables’ Cables’ Vision (1980) and fellow CTI veteran Joe Farrell’s Sonic Text (1981). One wonders why this record wasn’t on Contemporary as well.

Joining Hubbard on Mistral’s front line is West Coast jazz legend Art Pepper (also on Contemporary at the time). In their only known recording together, Hubbard and Pepper are linked by pianist George Cables, who was Hubbard’s pianist in the early seventies and Pepper’s pianist in the late seventies. Pepper is not an obvious foil for Hubbard. But he’s no slouch and his warm tone holds its own alongside the leader, particularly when Hubbard is on the flugelhorn.

Cables himself returned to Hubbard’s band after several albums together on CTI and Columbia in the mid-seventies (the two would pair up again on Hubbard’s 1981 acoustic set Back to Birdland).

Perhaps the most notable addition to the line-up is bass wunderkind Stanley Clarke, who was experiencing a burst of his own popularity at the time. Hubbard and Clarke were captured only briefly before this: the latter as guest on the former’s The Love Connection and the former as guest on the latter’s I Wanna Play For You (both 1979).

Trombonist Phil Ranelin returns from Skagly to take a tasty solo on “Bring it Back Home.”

Mistral is a solid slice of good fusion jazz, but maybe a bit more of its time than many of Hubbard’s CTI and Columbia albums. It isn’t programmed as strongly as it might have been: opening with the familiar “Sunshine Lady” doesn’t promise nearly as much as the set’s fiery closer, “Bring it Back Home.”

The program is typical for Hubbard during this time, a few originals (at least one burner and a ballad), the requisite standard (in this case, Cole Porter’s “I Love You”) and some band features. Highlights include Hubbard’s terrifically funky “Bring it Back Home” (handily driven by Cables, Clarke and drummer Peter Erskine) and George Cable’s moody “Blue Nights,” which was also recorded with lyrics around the same time for Japanese vocalist Anli Sugano’s Show Case, also on East World.