Say what you will about the P-Funk mob, and many people have, but those guys could play…and play and play and play. Despite whatever substances were aiding them along the way – and there many – there was plenty of raw talent, free-thinking and freedom-seeking attitude that fuelled this band’s musical invention and gave birth to one of the 20th century’s greatest musical concoctions.

Say what you will about the P-Funk mob, and many people have, but those guys could play…and play and play and play. Despite whatever substances were aiding them along the way – and there many – there was plenty of raw talent, free-thinking and freedom-seeking attitude that fuelled this band’s musical invention and gave birth to one of the 20th century’s greatest musical concoctions. Known under many guises, but most famously as Parliament, Funkadelic and Bootsy’s Rubber Band, the P-Funk cosmology was innovative in any number of ways, pioneering a new form of music that obviously mixed rock with R&B but was predicated upon a jazz-like innovation that borders on classical music.

Get behind all the often inane lyrics, even those that purported to have a serious message, cartoon chants and the helplessly addictive grooves, and you have some serious musical talent here, worthy of note on its own merit. This wasn’t merely funk. It was something deeper, altogether more serious than simple funk. It was THE funk.

The P-Funkseters were inventing a new musical language, peopling a whole new universe that no one had ever heard before. Overseen by George Clinton, equal parts P.T. Barnum and Teo Macero, the P-Funk crew was a sprawling, ever-changing amalgam of many, many individual talents, the most notable of whom were probably Eddie Hazel, Bernie Worrell and Bootsy Collins. (Please forgive me if I left anyone out – there was a plethora of talent to be heard here, nearly all of it significant – but the folks I named here strike me as much as architects of the P-Funk sound as contributors to it.)

After years of toiling in the otherwise hugely popular Detroit music scene during the late 50s and early 60s, mostly under the guise of The Parliaments, George Clinton discovered something truly unique when he let the musicians step forward into the spotlight to form Funkadelic, perhaps the world’s very first jam band. Funkadelic actually landed a recording contract with Detroit’s Westbound Records in 1969, and the group went on to shape a whole new sound for themselves and break a lot of musical barriers over the course of eight wildly divergent records through 1976, most memorably on 1971’s Maggot Brain. Clinton called it all “A Parliafunkdelicment Thang,” which is where the shorthanded P-Funk name came from, and it grew from there.

Clinton revived Parliament in 1974 as a much more soulful, somewhat more radio-friendly version of Funkadelic, bringing the vocalists back up front and replacing the guitar domination with layered keyboards and horny horns. It hit in 1975 when “Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker)” crossed over and became a huge radio sensation. Clinton started spreading his wings and expanding the organization (and label dealings) to feature multi-instrumentalist and former J.B., William “Bootsy” Collins, the back-up vocalists (Brides of Funkenstein, Parlet), the horn section, led by former J.B. Fred Wesley and featuring another former J.B., Maceo Parker, among many, many others including the group’s prominent instrumentalists, Eddie Hazel and Bernie Worrell.

There was so much music coming out of the P-Funk fold between 1977 and 1980 that some of it was either negligible or just slipped between the grooves of all the other stuff that lined the shelves. My intention here is not to cover the entirety of the voluminous P-Funk catalog nor review all the highlights that should be heard, savored or appreciated. Plenty has already been written about these guys and their music (check out The Motherpage for an excellent resource of all-things P-Funk) and chances are you already know what you like or what you want out of P-Funk.

The focus here is on some of the lesser-known music that either spotlights or should spotlight the P-Funk instrumentalists. Funkadelic is probably the best place to hear P-Funk’s most overt musicianship. Mostly a vehicle for guitarists Eddie Hazel and, later, Mike Hampton, Funkadelic was also a particularly creative canvas for keyboardist Bernie Worrell. It’s most apparent in the instrumentals, from Hazel’s magnum opus “Maggot Brain” (1971) to other (mostly) instrumentals including “You Hit The Nail On The Head” and “A Joyful Process” from 1972’s America Eats Its Young, “Nappy Dugout” from 1973’s Cosmic Slop, “Atmospheres” (a feature for Bernie Worrell) from 1975’s Let’s Take It To The Stage, “Tales of Kidd Funkadelic” from the 1976 album, “Hardcore Jollies” (featuring Hampton) from another 1976 album, “Lunchmeataphobia,” “P.E. Squad/Doodoo Chasers” and “Maggot Brain” from the hit One Nation Under A Groove, “Field Maneuvers” from 1979’s Uncle Jam Wants You) and superfluously on “Brettino’s Bounce” from 1981’s Electric Spanking of War Babies. It’s usually what’s going on behind – almost beyond – the vocals heard that makes Funkadelic most interesting and, ultimately, timelessly enduring.

The focus here is on some of the lesser-known music that either spotlights or should spotlight the P-Funk instrumentalists. Funkadelic is probably the best place to hear P-Funk’s most overt musicianship. Mostly a vehicle for guitarists Eddie Hazel and, later, Mike Hampton, Funkadelic was also a particularly creative canvas for keyboardist Bernie Worrell. It’s most apparent in the instrumentals, from Hazel’s magnum opus “Maggot Brain” (1971) to other (mostly) instrumentals including “You Hit The Nail On The Head” and “A Joyful Process” from 1972’s America Eats Its Young, “Nappy Dugout” from 1973’s Cosmic Slop, “Atmospheres” (a feature for Bernie Worrell) from 1975’s Let’s Take It To The Stage, “Tales of Kidd Funkadelic” from the 1976 album, “Hardcore Jollies” (featuring Hampton) from another 1976 album, “Lunchmeataphobia,” “P.E. Squad/Doodoo Chasers” and “Maggot Brain” from the hit One Nation Under A Groove, “Field Maneuvers” from 1979’s Uncle Jam Wants You) and superfluously on “Brettino’s Bounce” from 1981’s Electric Spanking of War Babies. It’s usually what’s going on behind – almost beyond – the vocals heard that makes Funkadelic most interesting and, ultimately, timelessly enduring. Such was especially true of Parliament, which rose above the clouds with 1974’s Up For The Down Stroke. This version of the Funk Mob had been configured to be much more commercial, so the vocals get moved to the front and horns, which gave other groups like Kool & The Gang, the Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire, their sonic signature, were added. Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell co-wrote many of the group’s songs and are prominently featured on a variety of instruments throughout the grooves but only “Night of the Thumpasorus Peoples” (featuring Bootsy and Bernie) from 1975’s Mothership Connection) and the disco-y “The Big Bang Theory” from 1979’s Gloryhallastoopid (Pin The Tail On The Funky) reveal the instrumental side of Parliament – though “Flash Light” remains a monster of instrumental magic that should be savored and could be studied for creative technological prowess for years to come.

Such was especially true of Parliament, which rose above the clouds with 1974’s Up For The Down Stroke. This version of the Funk Mob had been configured to be much more commercial, so the vocals get moved to the front and horns, which gave other groups like Kool & The Gang, the Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire, their sonic signature, were added. Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell co-wrote many of the group’s songs and are prominently featured on a variety of instruments throughout the grooves but only “Night of the Thumpasorus Peoples” (featuring Bootsy and Bernie) from 1975’s Mothership Connection) and the disco-y “The Big Bang Theory” from 1979’s Gloryhallastoopid (Pin The Tail On The Funky) reveal the instrumental side of Parliament – though “Flash Light” remains a monster of instrumental magic that should be savored and could be studied for creative technological prowess for years to come. The following represents specific albums that should figure in any collection of P-Funk where the instrumentalists and their contributions mattered. While none are entirely satisfactory as self-contained musical statements (there’s certainly no funked-up Kind of Blue, Electric Ladyland or even “Flash Light” in the bunch), each deserves kudos for spotlighting specific instrumentalists well-deserving of a much better testament to their musical powers than what was captured on any one record that’s been released – or at least covered below.

A Blow For Me, A Toot For You - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1977): By the time Fred Wesley helmed his own P-Funk date in 1977, he’d already racked up time as part of James Brown’s band and as leader of its more instrumental offshoot, the renowned J.B.’s (their last album was 1975’s Hustle With Speed). He’d also contributed to such CTI albums as Hank Crawford’s I Hear A Symphony, Hank Crawford’s Back and Cajun Sunrise, Idris Muhammad’s House Of The Rising Sun, George Benson’s Good King Bad, Esther Phillips’ For All We Know and David Matthews’ Shoogie Wanna Boogie - all arranged by fellow J.B. alum, David Matthews. So this guy had his jazz/funk chops well in line. By the time of this album, Fred Wesley and fellow J.B. and Horny Horn partner Maceo Parker had been a significant part of the Parliament/Funkadelic fold for nearly two years, starting with the hugely popular Mothership Connection album and the hit “Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker).” Fred, Maceo & Co. start their own newly dubbed “Horny Horns” project off here with a long, excellent cover of Parliament’s 1974 “Up For The Down Stroke,” replacing the original’s vocals with vocals by the Brides of Funkenstein, a great string arrangement and some incredibly subtle, yet bracing, acoustic piano work from Bernie Worrell (Maceo is heard jamming at the very end, as the disco-y song fades out). Next, “A Blow For Me..” is a satisfactory meeting of the minds between Bootsy Collins and Fred Wesley, with Bootsy providing the heavy bass line and both Fred and Maceo free-styling (in tandem with Bernie Worrell) on electronically-fitted instruments (great trumpet lines aid de camp). “When In Doubt: Vamp,” a Clinton-Gary Schider-Bernie Worrell “piece,” was pretty much how George Clinton operated his musical operation – especially live. But here, the title is attached to a well-heeled jazz romp that launches into a beatific and utterly catchy (Rick Gardner) trumpet-fuelled New Orleans groove. “Four Play” is as close as the group comes to sounding like James Brown here (you got to wonder who’s doing the guitar that places this piece so firmly in rival Brown’s camp - Bootsy or Catfish…both veterans of James Brown, just like Maceo and Fred). But, oh, what a sound. Fred solos magnificently here. With its “Casper The Friendly/Funky Ghost” theme, “Between Two Sheets” suggests an outtake from an early Rubber Band album (the Casper character figured largely in the first Bootsy album, Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band). But, aside from a number of P-Funk namedropping that happens throughout the tune, both Fred and Maceo get nice funky features here. The one surprise on this album – which, fortunately, has seen the light of day on CD – is Fred Wesley’s moody, beautiful and most un-funky “Peace Fugue.” Sounding like a film theme, something like Lalo Schifrin’s “Street Tattoo” (from Boulevard Nights) crossed with Bill Conti’s Uncle Joe Shannon (both 1978), “Peace Fugue” actually stands out. Maybe it’s not as funky something you’d expect on an album like this, but it’s the album’s single most engaging moment. This might just well be one of the best P-Funk albums ever.

A Blow For Me, A Toot For You - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1977): By the time Fred Wesley helmed his own P-Funk date in 1977, he’d already racked up time as part of James Brown’s band and as leader of its more instrumental offshoot, the renowned J.B.’s (their last album was 1975’s Hustle With Speed). He’d also contributed to such CTI albums as Hank Crawford’s I Hear A Symphony, Hank Crawford’s Back and Cajun Sunrise, Idris Muhammad’s House Of The Rising Sun, George Benson’s Good King Bad, Esther Phillips’ For All We Know and David Matthews’ Shoogie Wanna Boogie - all arranged by fellow J.B. alum, David Matthews. So this guy had his jazz/funk chops well in line. By the time of this album, Fred Wesley and fellow J.B. and Horny Horn partner Maceo Parker had been a significant part of the Parliament/Funkadelic fold for nearly two years, starting with the hugely popular Mothership Connection album and the hit “Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker).” Fred, Maceo & Co. start their own newly dubbed “Horny Horns” project off here with a long, excellent cover of Parliament’s 1974 “Up For The Down Stroke,” replacing the original’s vocals with vocals by the Brides of Funkenstein, a great string arrangement and some incredibly subtle, yet bracing, acoustic piano work from Bernie Worrell (Maceo is heard jamming at the very end, as the disco-y song fades out). Next, “A Blow For Me..” is a satisfactory meeting of the minds between Bootsy Collins and Fred Wesley, with Bootsy providing the heavy bass line and both Fred and Maceo free-styling (in tandem with Bernie Worrell) on electronically-fitted instruments (great trumpet lines aid de camp). “When In Doubt: Vamp,” a Clinton-Gary Schider-Bernie Worrell “piece,” was pretty much how George Clinton operated his musical operation – especially live. But here, the title is attached to a well-heeled jazz romp that launches into a beatific and utterly catchy (Rick Gardner) trumpet-fuelled New Orleans groove. “Four Play” is as close as the group comes to sounding like James Brown here (you got to wonder who’s doing the guitar that places this piece so firmly in rival Brown’s camp - Bootsy or Catfish…both veterans of James Brown, just like Maceo and Fred). But, oh, what a sound. Fred solos magnificently here. With its “Casper The Friendly/Funky Ghost” theme, “Between Two Sheets” suggests an outtake from an early Rubber Band album (the Casper character figured largely in the first Bootsy album, Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band). But, aside from a number of P-Funk namedropping that happens throughout the tune, both Fred and Maceo get nice funky features here. The one surprise on this album – which, fortunately, has seen the light of day on CD – is Fred Wesley’s moody, beautiful and most un-funky “Peace Fugue.” Sounding like a film theme, something like Lalo Schifrin’s “Street Tattoo” (from Boulevard Nights) crossed with Bill Conti’s Uncle Joe Shannon (both 1978), “Peace Fugue” actually stands out. Maybe it’s not as funky something you’d expect on an album like this, but it’s the album’s single most engaging moment. This might just well be one of the best P-Funk albums ever.  Games Dames And Guitar Thangs - Eddie Hazel (Warner Bros., 1978): At the time of its release, guitarist Eddie Hazel’s debut – and sole – solo album was disappointing because of its odd choice of material and its very un-Parliament sound. It was probably nearly two decades later when I discovered the early Funkadelic records co-strategized by the unpredictable Hazel that I found this album further disappointing because that Hendrix edge Hazel had fostered – and nearly made his own - in the early 70s seemed now to lack focus, direction or even purpose in the disco age. And why the “California Dreamin’” cover? (This was also the 45-inch single Warner Bros. attempted to launch Hazel’s solo career with too. OK – yes, many acts at the time were getting weirdly famous redoing old hits from the 50s and 60s…but it was hard to believe that a flower-power hit could score in the age of Saturday Night Fever or even Grease.) As another decade or so has passed, I have finally warmed up to this rather hit-or-miss affair. At the time, personal problems prevented Hazel from devoting full attention to P-Funk, which – as a helmsman of Funkadelic – he left in 1971 and returned, sporadically, to in 1974 (Hazel isn’t heard on any of the Parliament or Funkadelic radio hits made around this time). But he and George Clinton assembled much of the P-Funk mob, including Bootsy Collins, Mike Hampton, the Brides of Funkenstein on background vocals on a few tracks and, notably, Bernie Worrell, and created a genuinely interesting document that attests fairly decently to the incredible talents of guitar god Eddie Hazel. It’s still a hard album to figure. There is good musicianship throughout. But any expectation that was there was to be confounded. By 1978, when this album was issued – with little or no fanfare whatsoever – who wanted to hear a black rock guitarist trying to do outmoded pop or try to get into the funked-up cartoons P-Funk was making millions off of? Even Eddie Hazel seems to have trouble figuring out how to fit into any concept that would have worked in 1978. Still, he succeeds in wrenching meaning out of this barely successful jazz-rock experiment. Hazel, in all his glory, is heard absolutely in his element in “So Goes The Story.” But the first notable piece is the surprising cover of The Beatles’ “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” which predates the Robert Stigwood-produced Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band extravaganza by a few weeks. Why wasn’t Hazel asked to contribute to this film? Hazel is astronomical here: everything you want and expect from the guitarist – a genius, set alight by an incendiary Beatles tune. Doesn’t seem like something Funkadelic would touch (though there was an odd cover of “She Loves You” on 1981’s The Electric Spanking of War Babies). But Hazel – again – nearly makes it his own. “Physical Love” is the same tune heard on Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band (Warner Bros., 1976) with Hazel’s guitar replacing the vocalists on Bootsy’s version. Hazel gives this song the heated passion Bootsy’s near-goofy version somehow lacks (although Garry Shider’s guitar and Bernie Worrell’s synth solo give this piece some of the greatness it probably deserves). Perhaps it’s the pain of desire. It sings out. The album’s stand-out track is the all-too brief bit of electro funk called “What About It?,” credited to both Eddie Hazel and George Clinton. It’s a brilliant instrumental that shows Hazel’s penchant for riveting guitarisms and a funky edge (remember The Temp’s great “Shakey Ground”?). It also boasts some of the great guitartastics Mike Hampton brought to the P-fold. It would have been fascinating if Hazel (or Clinton) let the whole album drive down this path. Still, it’s a great listen, if never wholly satisfying. Hazel continued recording with the P-Funk mob on and off until his death in December 1992. An EP with Hazel-oriented outtakes titled Jams From The Heart was issued in 1994 and folded, with different titles, into another release called Rest In P. But to hear one of the great Eddie Hazel P-Funk concoctions from this period (while he was Bonnie Pointer’s musical director), check out “I’m Holding You Responsible” from The Brides of Funkenstein’s Never Buy Texas From A Cowboy (Atlantic, 1979).

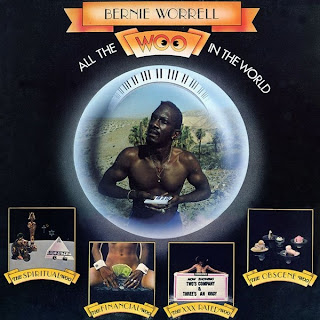

Games Dames And Guitar Thangs - Eddie Hazel (Warner Bros., 1978): At the time of its release, guitarist Eddie Hazel’s debut – and sole – solo album was disappointing because of its odd choice of material and its very un-Parliament sound. It was probably nearly two decades later when I discovered the early Funkadelic records co-strategized by the unpredictable Hazel that I found this album further disappointing because that Hendrix edge Hazel had fostered – and nearly made his own - in the early 70s seemed now to lack focus, direction or even purpose in the disco age. And why the “California Dreamin’” cover? (This was also the 45-inch single Warner Bros. attempted to launch Hazel’s solo career with too. OK – yes, many acts at the time were getting weirdly famous redoing old hits from the 50s and 60s…but it was hard to believe that a flower-power hit could score in the age of Saturday Night Fever or even Grease.) As another decade or so has passed, I have finally warmed up to this rather hit-or-miss affair. At the time, personal problems prevented Hazel from devoting full attention to P-Funk, which – as a helmsman of Funkadelic – he left in 1971 and returned, sporadically, to in 1974 (Hazel isn’t heard on any of the Parliament or Funkadelic radio hits made around this time). But he and George Clinton assembled much of the P-Funk mob, including Bootsy Collins, Mike Hampton, the Brides of Funkenstein on background vocals on a few tracks and, notably, Bernie Worrell, and created a genuinely interesting document that attests fairly decently to the incredible talents of guitar god Eddie Hazel. It’s still a hard album to figure. There is good musicianship throughout. But any expectation that was there was to be confounded. By 1978, when this album was issued – with little or no fanfare whatsoever – who wanted to hear a black rock guitarist trying to do outmoded pop or try to get into the funked-up cartoons P-Funk was making millions off of? Even Eddie Hazel seems to have trouble figuring out how to fit into any concept that would have worked in 1978. Still, he succeeds in wrenching meaning out of this barely successful jazz-rock experiment. Hazel, in all his glory, is heard absolutely in his element in “So Goes The Story.” But the first notable piece is the surprising cover of The Beatles’ “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” which predates the Robert Stigwood-produced Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band extravaganza by a few weeks. Why wasn’t Hazel asked to contribute to this film? Hazel is astronomical here: everything you want and expect from the guitarist – a genius, set alight by an incendiary Beatles tune. Doesn’t seem like something Funkadelic would touch (though there was an odd cover of “She Loves You” on 1981’s The Electric Spanking of War Babies). But Hazel – again – nearly makes it his own. “Physical Love” is the same tune heard on Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band (Warner Bros., 1976) with Hazel’s guitar replacing the vocalists on Bootsy’s version. Hazel gives this song the heated passion Bootsy’s near-goofy version somehow lacks (although Garry Shider’s guitar and Bernie Worrell’s synth solo give this piece some of the greatness it probably deserves). Perhaps it’s the pain of desire. It sings out. The album’s stand-out track is the all-too brief bit of electro funk called “What About It?,” credited to both Eddie Hazel and George Clinton. It’s a brilliant instrumental that shows Hazel’s penchant for riveting guitarisms and a funky edge (remember The Temp’s great “Shakey Ground”?). It also boasts some of the great guitartastics Mike Hampton brought to the P-fold. It would have been fascinating if Hazel (or Clinton) let the whole album drive down this path. Still, it’s a great listen, if never wholly satisfying. Hazel continued recording with the P-Funk mob on and off until his death in December 1992. An EP with Hazel-oriented outtakes titled Jams From The Heart was issued in 1994 and folded, with different titles, into another release called Rest In P. But to hear one of the great Eddie Hazel P-Funk concoctions from this period (while he was Bonnie Pointer’s musical director), check out “I’m Holding You Responsible” from The Brides of Funkenstein’s Never Buy Texas From A Cowboy (Atlantic, 1979). All The Woo In The World - Bernie Worrell (Arista, 1979): Much like a Herbie Hancock or Miles Davis album, one comes to a Bernie Worrell album with impossibly high expectations. Unfortunately, the piano prodigy and key P-Funk keyboardist/writer/arranger/musical director/conceptualist’s 1979 solo recording debut – unlike any other P-Funk act, on Arista Records – is, perhaps, the least notable album in the entire P-Funk catalog and probably the least interesting album that ever carried Mr. Worrell’s name. Seemingly cobbled together from P-Funk’s studio leftovers, All The Woo In The World comes across as an audio typo, a mistake that seems heaped on Worrell’s shoulders. Nearly absent is any evidence of the wizardry Worrell used in the studio to build some of the most notable music of the 20th century. Indeed, other than taking a majority of the lead vocals, Worrell the writer and Worrell the keyboard maestro seems not to ever have been a consideration for the first album bearing his own name. The songs aren’t that bad, but none are all that interesting. “Woo Together” gives birth to Worrell’s enduring “Woo” concept, which was probably derived from the “Pleasure Principle” song he co-wrote and arranged for Parlet’s 1978 album of the same name and is most notable for Motown arranger David Van De Pitte’s funky strings. The soulful “I’ll Be With You” is a mostly vocal piece that turns out to be the album’s most interesting track, capped off with Bernie’s Ramsey Lewis-like piano solo overdubbed atop his own electric ruminations. The otherwise negligible “Happy To Have (Happiness On Our Side)” also benefits from a pokey piano solo, but Worrell plays it as if he’s not sure whether it will be faded out in mid-thought or erased in the final edit. “Much Thrust” is tailor-made Funkadelic, but the guitar (probably by Mike “Kidd Funkadelic” Hampton) dominates where Worrell should. The silly Parliament-like “Insurance Man For The Funk” puts P-Funk overlord George Clinton out in front, welcomes the Horny Horns, features Maceo Parker’s noodling, gets a brief Bootsy respite and evidences some of the keyboard sounds Worrell was heard to layer on other P-Funk classics. But while “Insurance Man For The Funk” has become a cult classic, it keeps plodding along long after the simple groove is worn thin and the joke has been beaten to death (it also has one of the most anti-climactic bridges in all of P-Funk’s funkentelechy). All The Woo In The World is certainly some of the least interesting P-Funk ever waxed. But Bernie Worrell, who sounds like he’s along on someone else’s ride, deserved a whole lot better start than this. Check out Blacktronic Science (Gramavision, 1993) or Improvisczario (Godforsaken Music, 2007) to hear the wonderful Woo of Bernie Worrell. Also, see the riveting documentary, Stranger: Bernie Worrell on Earth (2007) to experience the great Bernie Worrell on a number of worthy and well-deserving planes of appreciation and acceptance.

All The Woo In The World - Bernie Worrell (Arista, 1979): Much like a Herbie Hancock or Miles Davis album, one comes to a Bernie Worrell album with impossibly high expectations. Unfortunately, the piano prodigy and key P-Funk keyboardist/writer/arranger/musical director/conceptualist’s 1979 solo recording debut – unlike any other P-Funk act, on Arista Records – is, perhaps, the least notable album in the entire P-Funk catalog and probably the least interesting album that ever carried Mr. Worrell’s name. Seemingly cobbled together from P-Funk’s studio leftovers, All The Woo In The World comes across as an audio typo, a mistake that seems heaped on Worrell’s shoulders. Nearly absent is any evidence of the wizardry Worrell used in the studio to build some of the most notable music of the 20th century. Indeed, other than taking a majority of the lead vocals, Worrell the writer and Worrell the keyboard maestro seems not to ever have been a consideration for the first album bearing his own name. The songs aren’t that bad, but none are all that interesting. “Woo Together” gives birth to Worrell’s enduring “Woo” concept, which was probably derived from the “Pleasure Principle” song he co-wrote and arranged for Parlet’s 1978 album of the same name and is most notable for Motown arranger David Van De Pitte’s funky strings. The soulful “I’ll Be With You” is a mostly vocal piece that turns out to be the album’s most interesting track, capped off with Bernie’s Ramsey Lewis-like piano solo overdubbed atop his own electric ruminations. The otherwise negligible “Happy To Have (Happiness On Our Side)” also benefits from a pokey piano solo, but Worrell plays it as if he’s not sure whether it will be faded out in mid-thought or erased in the final edit. “Much Thrust” is tailor-made Funkadelic, but the guitar (probably by Mike “Kidd Funkadelic” Hampton) dominates where Worrell should. The silly Parliament-like “Insurance Man For The Funk” puts P-Funk overlord George Clinton out in front, welcomes the Horny Horns, features Maceo Parker’s noodling, gets a brief Bootsy respite and evidences some of the keyboard sounds Worrell was heard to layer on other P-Funk classics. But while “Insurance Man For The Funk” has become a cult classic, it keeps plodding along long after the simple groove is worn thin and the joke has been beaten to death (it also has one of the most anti-climactic bridges in all of P-Funk’s funkentelechy). All The Woo In The World is certainly some of the least interesting P-Funk ever waxed. But Bernie Worrell, who sounds like he’s along on someone else’s ride, deserved a whole lot better start than this. Check out Blacktronic Science (Gramavision, 1993) or Improvisczario (Godforsaken Music, 2007) to hear the wonderful Woo of Bernie Worrell. Also, see the riveting documentary, Stranger: Bernie Worrell on Earth (2007) to experience the great Bernie Worrell on a number of worthy and well-deserving planes of appreciation and acceptance. Say Blow By Blow Backwards - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1979): The second Horny Horns album has its share of interesting moments. But the disjointed, unfocused music and its odd and not very clever title (seemingly suggesting an anagram) suggest there may have been a contractual obligation here. It’s almost as if there wasn’t the time or the inclination to put a good Horny Horns record together in the first place. But this was also the year of such ambitious – and ultimately unsuccessful – concepts as Gloryhallastoopid and Uncle Jam Wants You. Significantly, it’s also one of the few P-Funk albums that carries few writing credits for George Clinton, suggesting his input was minimal or entirely negligible. The album opens with Bootsy Collins’ light-weight anthem, “We Came To Funk Ya,” a prototypical Rubber Band chant that seems like little more than a “Bootzilla” knock-off with Wesley and Parker taking marginally interesting solos, driven along by Bootsy’s distinctive bass. Up next is Billy (Bass) Nelson’s excellent “Half A Man,” a soulful rocker that would have sounded right at home on either a Funkadelic album (circa 1976) or a Parliament album (circa 1975-76). Trouble is, it just doesn’t sound right here. Fred and Maceo only factor in the background horn charts as they did so beautifully on so many P-Funk albums at the time. But here, it’s not about either one of them at all. So even at nine and a half minutes, there’s surprisingly little Horny Horn action and a song that probably deserved to be a hit never found its way out of this half-baked album. Wesley’s title track is a key moment for the Horny Horns, a great groove and some of the most substantial improvising both Parker and especially Wesley ever laid down on a P-Funk track. This one and Wesley’s other contribution here, the fun and fascinating “Circular Motion,” are the ones to hear and probably the only two songs that deserve the Horny Horns moniker. “Mr. Melody Man” is a feature for Maceo, who gets the lion’s share of solos throughout (just like in the Rubber Band, where Maceo also served as MC) – leading one to wonder how or why the P-Funk organization never gave Maceo any of his own solo albums. “Just Like You,” originally heard with vocals on The Brides of Funkenstein’s album Funk of Walk (Atlantic, 1979), is here turned into the type of power ballad Giorgio Moroder made famous the following year with his love theme to American Gigolo (“The Seduction”). It’s another feature solely for Maceo Parker. But at six minutes and 47 seconds and umpteen musical climaxes, it’s far too long and loses steam long after the minimal passion that was there in the first place is gone (the Brides milked it for a full nine minutes!). Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a player here, would have never let that happen. Seems there are a great many pieces of fat here that a good overlord or musical doctor would have trimmed or never allowed. Still, there’s probably 21 worthy minutes of music here that are worth checking out. Unfortunately, it’s hardly enough to justify a full album, much less a CD, release. For completists, a third Horny Horns album titled, ironically (and humorously) enough, The Final Blow was issued on CD in 1994. Comprised of outtakes and unfinished numbers – which Fred Wesley has since disavowed – it completes the unfortunately slim and artistically unsatisfying discography (especially compared to the J.B.’s output) of the otherwise brilliant Horny Horns.

Say Blow By Blow Backwards - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1979): The second Horny Horns album has its share of interesting moments. But the disjointed, unfocused music and its odd and not very clever title (seemingly suggesting an anagram) suggest there may have been a contractual obligation here. It’s almost as if there wasn’t the time or the inclination to put a good Horny Horns record together in the first place. But this was also the year of such ambitious – and ultimately unsuccessful – concepts as Gloryhallastoopid and Uncle Jam Wants You. Significantly, it’s also one of the few P-Funk albums that carries few writing credits for George Clinton, suggesting his input was minimal or entirely negligible. The album opens with Bootsy Collins’ light-weight anthem, “We Came To Funk Ya,” a prototypical Rubber Band chant that seems like little more than a “Bootzilla” knock-off with Wesley and Parker taking marginally interesting solos, driven along by Bootsy’s distinctive bass. Up next is Billy (Bass) Nelson’s excellent “Half A Man,” a soulful rocker that would have sounded right at home on either a Funkadelic album (circa 1976) or a Parliament album (circa 1975-76). Trouble is, it just doesn’t sound right here. Fred and Maceo only factor in the background horn charts as they did so beautifully on so many P-Funk albums at the time. But here, it’s not about either one of them at all. So even at nine and a half minutes, there’s surprisingly little Horny Horn action and a song that probably deserved to be a hit never found its way out of this half-baked album. Wesley’s title track is a key moment for the Horny Horns, a great groove and some of the most substantial improvising both Parker and especially Wesley ever laid down on a P-Funk track. This one and Wesley’s other contribution here, the fun and fascinating “Circular Motion,” are the ones to hear and probably the only two songs that deserve the Horny Horns moniker. “Mr. Melody Man” is a feature for Maceo, who gets the lion’s share of solos throughout (just like in the Rubber Band, where Maceo also served as MC) – leading one to wonder how or why the P-Funk organization never gave Maceo any of his own solo albums. “Just Like You,” originally heard with vocals on The Brides of Funkenstein’s album Funk of Walk (Atlantic, 1979), is here turned into the type of power ballad Giorgio Moroder made famous the following year with his love theme to American Gigolo (“The Seduction”). It’s another feature solely for Maceo Parker. But at six minutes and 47 seconds and umpteen musical climaxes, it’s far too long and loses steam long after the minimal passion that was there in the first place is gone (the Brides milked it for a full nine minutes!). Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a player here, would have never let that happen. Seems there are a great many pieces of fat here that a good overlord or musical doctor would have trimmed or never allowed. Still, there’s probably 21 worthy minutes of music here that are worth checking out. Unfortunately, it’s hardly enough to justify a full album, much less a CD, release. For completists, a third Horny Horns album titled, ironically (and humorously) enough, The Final Blow was issued on CD in 1994. Comprised of outtakes and unfinished numbers – which Fred Wesley has since disavowed – it completes the unfortunately slim and artistically unsatisfying discography (especially compared to the J.B.’s output) of the otherwise brilliant Horny Horns. Sweat Band - Sweat Band (Uncle Jam, 1980): Between 1976 and 1979, Bootsy’s Rubber Band was a hugely successful offshoot of the P-Funk mothership, distinguished by equal parts funk (emphasizing Bootsy’s “Space Bass”) and silky soulful balladry. Despite Collins’ cartoon-y antics and somewhat goofy lyrics, the Rubber Band was often more “musical” than the rest of P-Funk, probably due to the high musicianship Collins himself brought to the endeavor. Very little that could be considered jazz or jazzy came out of it all but the music was tight and much more disciplined than the other P-Funk units, something Mr. Collins no doubt gleaned from his time with James Brown. The Horny Horns were featured heavily throughout, with Fred Wesley covering the charts and sidekick/emcee Maceo getting a high dose of solo spots. The best stuff out of the Rubber Band showed how well it all worked. Sample “Stretchin’ Out,” “Psychoticbumpschool” and “Another Point of View” from Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band; “Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy Baby,” “The Pinocchio Theory,” and “Rubber Duckie” from Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy Baby; “What’s The Name Of This Town,” “Bootzilla” and “Roto-Rooter” from Bootsy? Player of The Year; and “Bootsy Get Live” and “Jam Fan” from This Boot Is Made For Fonk-n. By 1980, Bootsy spread his wings a bit and launched the Sweat Band, a more instrumental version of the Rubber Band, on George Clinton’s newly devised CBS subsidiary, Uncle Jam Records. The album opens with the bracing electro-instrumental, “Hyper Space,” nearly disclaiming any similarity to anything in the P-Funk cannon and nothing at all like the Rubber Band. Driven by synth-man and co-writer Joel “Razor Sharp” Johnson and peppered nicely by guitarist Mike Hampton, it almost suggests a European action film theme of the time – a great dance piece, which could work well to highlight action on the silver screen – or just as effectively on the mirror-balled dance floor. This is the kind of thing everyone was hoping Prince would come up with at the time. Next follows the dance hit “Freak To Freak,” a good groove that suggests what the next phase of Bootsy’s Rubber Band could have been but never was - groovy guitar, funky bass, electric drums and programmed handclaps. (Sweat Band was issued on CD in Japan in the 1990s and is now long out of print, but “Freak To Freak” appears on 6 Degrees of P-Funk: The Best of George Clinton and his Funky Family, a CD compilation of Clinton’s Columbia projects made during the 1980s.) “Love Munch” is a poppy piece of jazz fusion that sits easily alongside anything Spyro Gyra was doing at the time, were it not for Maceo Parker’s gripping and hiccupping sax taking it somewhere stratospheric that’s well worth following. With Bootsy’s aggressive “Space Bass” and all-over-the-map percussion, “Jamaica” is the closest Bootsy and Maceo ever came to successfully melding the J.B’s sound with the P-Funk groove. The chant “Jamaica – take me to your jungle” paves the way for Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s next stop, a decade later, on the funky career overview, “Jungle Bass” (4th & B’way, 1990). “Body Shop” and “We Do It All Day Long” (heard in brief on side one before the full version, subtitled “Reprise,” is heard on side two) sound like above average P-Funk grooves left off of other P-Funk albums because they are straight party tunes and not sci-fi concepts or some off-the-wall comical piece. Both are Bootsy conceptions co-written with P-Funk guitarist and vocalist Gary Shider, with the Brides of Funkenstein and Parlet chanting throughout in a typical David Bowie-meets-Fred Flinstone sort of wackiness. Bootsy’s Space Bass drives both pieces along with enormous propulsion, highlighted by some tasty keyboard work that is, sadly, not by Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a contributor here. Sweat Band ranks high among P-Funk’s 1980 output, which included Parliament’s regrettable Trombipulation and Bootsy’s inconsequential Ultra Wave, easily making this one of the essential P-Funk albums to own, despite the presence of one of the worst and least P-Funk looking album covers in the entire P-Funk discography (other than the 1983 P-Funk All Stars album Urban Dancefloor Guerrillas).

Sweat Band - Sweat Band (Uncle Jam, 1980): Between 1976 and 1979, Bootsy’s Rubber Band was a hugely successful offshoot of the P-Funk mothership, distinguished by equal parts funk (emphasizing Bootsy’s “Space Bass”) and silky soulful balladry. Despite Collins’ cartoon-y antics and somewhat goofy lyrics, the Rubber Band was often more “musical” than the rest of P-Funk, probably due to the high musicianship Collins himself brought to the endeavor. Very little that could be considered jazz or jazzy came out of it all but the music was tight and much more disciplined than the other P-Funk units, something Mr. Collins no doubt gleaned from his time with James Brown. The Horny Horns were featured heavily throughout, with Fred Wesley covering the charts and sidekick/emcee Maceo getting a high dose of solo spots. The best stuff out of the Rubber Band showed how well it all worked. Sample “Stretchin’ Out,” “Psychoticbumpschool” and “Another Point of View” from Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band; “Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy Baby,” “The Pinocchio Theory,” and “Rubber Duckie” from Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy Baby; “What’s The Name Of This Town,” “Bootzilla” and “Roto-Rooter” from Bootsy? Player of The Year; and “Bootsy Get Live” and “Jam Fan” from This Boot Is Made For Fonk-n. By 1980, Bootsy spread his wings a bit and launched the Sweat Band, a more instrumental version of the Rubber Band, on George Clinton’s newly devised CBS subsidiary, Uncle Jam Records. The album opens with the bracing electro-instrumental, “Hyper Space,” nearly disclaiming any similarity to anything in the P-Funk cannon and nothing at all like the Rubber Band. Driven by synth-man and co-writer Joel “Razor Sharp” Johnson and peppered nicely by guitarist Mike Hampton, it almost suggests a European action film theme of the time – a great dance piece, which could work well to highlight action on the silver screen – or just as effectively on the mirror-balled dance floor. This is the kind of thing everyone was hoping Prince would come up with at the time. Next follows the dance hit “Freak To Freak,” a good groove that suggests what the next phase of Bootsy’s Rubber Band could have been but never was - groovy guitar, funky bass, electric drums and programmed handclaps. (Sweat Band was issued on CD in Japan in the 1990s and is now long out of print, but “Freak To Freak” appears on 6 Degrees of P-Funk: The Best of George Clinton and his Funky Family, a CD compilation of Clinton’s Columbia projects made during the 1980s.) “Love Munch” is a poppy piece of jazz fusion that sits easily alongside anything Spyro Gyra was doing at the time, were it not for Maceo Parker’s gripping and hiccupping sax taking it somewhere stratospheric that’s well worth following. With Bootsy’s aggressive “Space Bass” and all-over-the-map percussion, “Jamaica” is the closest Bootsy and Maceo ever came to successfully melding the J.B’s sound with the P-Funk groove. The chant “Jamaica – take me to your jungle” paves the way for Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s next stop, a decade later, on the funky career overview, “Jungle Bass” (4th & B’way, 1990). “Body Shop” and “We Do It All Day Long” (heard in brief on side one before the full version, subtitled “Reprise,” is heard on side two) sound like above average P-Funk grooves left off of other P-Funk albums because they are straight party tunes and not sci-fi concepts or some off-the-wall comical piece. Both are Bootsy conceptions co-written with P-Funk guitarist and vocalist Gary Shider, with the Brides of Funkenstein and Parlet chanting throughout in a typical David Bowie-meets-Fred Flinstone sort of wackiness. Bootsy’s Space Bass drives both pieces along with enormous propulsion, highlighted by some tasty keyboard work that is, sadly, not by Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a contributor here. Sweat Band ranks high among P-Funk’s 1980 output, which included Parliament’s regrettable Trombipulation and Bootsy’s inconsequential Ultra Wave, easily making this one of the essential P-Funk albums to own, despite the presence of one of the worst and least P-Funk looking album covers in the entire P-Funk discography (other than the 1983 P-Funk All Stars album Urban Dancefloor Guerrillas).

3 comments:

As mach as i' am 80% opposed on your very informativ views about all Things concerning Creed Taylor, CTI and Kudu, as much am i pleased about your very well informed Essay concerning the ParliaFunkadelicement Thang.

Charlea Atan (Sir Nose devout to FunK)

чтобы добавлять свои статьи, обязательно ли регистрироватся?

Quantum Binary Signals

Get professional trading signals sent to your cell phone every day.

Start following our signals today and earn up to 270% daily.

Post a Comment