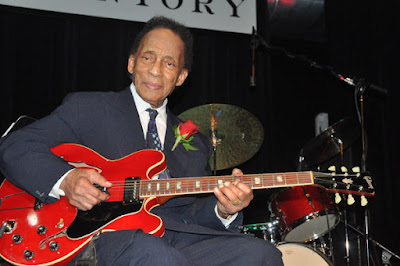

In a recording career that spans nearly eight decades, guitarist George Freeman (b. 1927) can be heard on only a handful of discs: some by others and fewer yet by Freeman himself.

One reason for this is that Freeman wasn’t often credited on his sessions for others (particularly in the forties and the fifties). Another reason is that Freeman always went back home to Chicago when he got tired of gigging to be with family and occasionally lead a trio of his own.

George Freeman, brother of Von and uncle to Chico, has played with sax greats Charlie Parker, Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt. He’s traveled the R&B circuit with Sil Austin and Jackie Wilson and done his time in the organ combos of Wild Bill Davis, Richard “Groove” Holmes and Jimmy McGriff.

While George Freeman was never as prolifically recorded as other guitarists of his generation – say, Joe Pass or Kenny Burrell – the sound he put out on guitar was unlike anything heard before or since. His tone could be pretty, but often raw and aggressive. It’s the sound of feeling. Also, his phrasing could be melodic, but charges more like a leader on a horn than a section mate who takes a solo.

"There is virtually no precedent,” wrote tenor saxophonist, bandleader, educator, scholar, author and The Good Life producer Loren Schoenberg in his notes to a 1998 Charlie Parker compilation, “for the outrageously experimental music that George Freeman creates…[His playing] is unlike anything I have ever heard, and seems much closer to what John Scofield and Bill Frisell have brought to the jazz guitar in the '90s than to anything from his own contemporaries.”

In other words, once you hear George Freeman, you pay attention – as though a whole new sound and groove had taken over and a song becomes immediately transformed. The music takes on a totally new meaning and requires a whole new way of hearing.

Even an organ trio is amped up by Freeman’s presence. Check out the way he steals the show and shreds – before it was even a thing – on Jimmy McGriff’s “Freedom Suite (Part 2)” or Groove Holmes’ “Licks a Plenty” (both 1973, although Freeman can be heard to superb effect on the 1961 version of the latter tune with Ben Webster). On that latter recording, Freeman brings out a whole new meaning to the titles “Out of Nowhere” and “The Squirrel” as well.

Consider, too, the remarkably sizzling and scintillating “Jug Eyes” and the guitarist’s own “The Black Cat” from saxophonist Gene Ammons’ 1971 album The Black Cat!. And, of course, there is the psychedelic acid-jazz classic “The Bump” from Freeman’s 1973 rarity Franticdiagnosis.

Once you hear George Freeman, you’ll want to hear more.

That brings us to The Good Life, which, by my count, is only George Freeman’s twelfth album as a leader. To celebrate his 95th birthday in 2022, George convened two trios: one in May with bassist Christian McBride and drummer Carl Allen and another in June with organist Joey DeFrancesco and drummer Lewis Nash.

Surprisingly, or maybe not, Freeman had never worked with either McBride or DeFrancesco, yet, unfortunately, The Good Life seems to be the organ player’s final recording. Joey DeFrancesco died only two months after this date with Freeman.

Throughout, this nonagenarian is in especially fine fettle. While maybe not as fleet as he used to be – or maybe no longer in need of standing out – the guitarist is never less than witty, even feisty. He is, by turns, playful yet precise; sly yet succinct, and always warm, wise and wonderful. He’s clearly having fun here, playing, indeed, as though he’s living “the good life.”

The program is mostly made up of George Freeman’s bluesy originals, bookended by the jazz standard “If I Had You” (with DeFrancesco) and Sacha Distel’s popular “The Good Life” (with McBride). With his solos on these two pieces, however, the guitarist reveals his characteristic resolve of exploring the more unchartered waters of the otherwise well-known songs: not so much deconstructing, but reconstructing. As ever, his playing commands attention.

While there’s not a dud in the bunch, the disc’s highlight is surely Freeman’s “Lowe Groovin,” from the trio with McBride. The song dates back to the mid-forties when Freeman played it with trumpeter Joe Morris’s orchestra, a group that also featured Johnny Griffin.

When the song was released on record in 1948, it was wrongly credited to Morris – a move that caused Freeman to leave the band. By the eighties, Freeman was able to reclaim credit for the song and its publishing rights.

Here, Freeman and McBride turn the heat way down “lowe” to a smokey, smoking blues. It’s a stark contrast to the jumpy R&B of the original and contains many fine moments in its all-too brief six minutes (replete with the guitarist’s devilishly clever quote of “You Came a Long Way from St. Louis”).

It’s a shame that Defrancesco and McBride aren’t heard together here – as they occasionally had been as far back as Joey’s 1993 Part III and as recently as Christian’s marvelous big band outing For Jimmy, Wes and Oliver (2020).

Here, Joey shines on “Mr. D,” written by the guitarist especially for the late, great and much-missed organist, and “Up and Down,” while Christian rocks, as expected, throughout, most notably on “Lowe Groovin” and “Sister Tankersley,” written by the guitarist for his mother, who lived to be 101.

The disc’s affectionate liner notes were written by producer Michael Cuscuna, who, in a nice “full circle” moment, financed and produced George Freeman’s 1969 recording debut, Birth Sign. Cuscuna “discovered” Freeman back in 1968 while writing the notes for the album The Astonishing Mickey Fields, where the tenor saxophonist was backed by Groove Holmes’ group, featuring George Freeman.

One could wish for a full disc’s worth of material from both sessions. But what is here is absorbing, often bracing and always enjoyable. Five guys just a-sittin’ and a-rockin’.

The Good Life is good jazz.

No comments:

Post a Comment