The prodigiously adaptable, prolifically recorded and always engaging guitarist Kenny Burrell had previously factored in orchestras accompanying such singers as Billie Holiday, Jimmy Witherspoon, Dinah Washington and Tony Bennett.

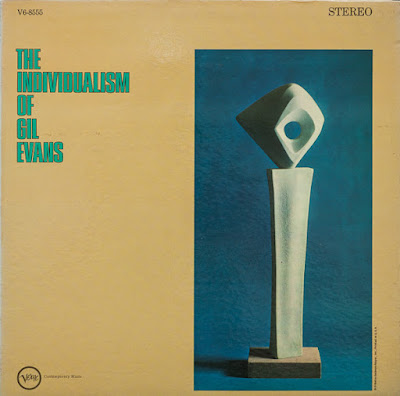

He was also one of Creed Taylor’s go-to session guys, appearing on Verve records by Kai Winding, Johnny Hodges, Cal Tjader and, notably, Jimmy Smith. Burrell was also one of the key contributors to the aforementioned The Individualism of Gil Evans.

After a long series of albums under his own name – mostly, but not solely, for the Prestige label – Kenny Burrell was offered an opportunity by Verve producer Creed Taylor to record an album arranged and conducted by the one and only Gil Evans. What musician worth his (or her) salt could turn down such an offer? Of course, Kenny Burrell agreed.

That album, Guitar Forms, is only sporadically orchestral – and notably subtle when it is. But it is a bravura showcase of Kenny Burrell’s acuity, vast gifts and ever-enduring appeal.

The nine tracks appearing on the original LP were recorded over four sessions, two in December 1964 (with Gil Evans and an orchestra) and two in April 1965 (in a small-group setting – audibly without Evans and company). While it is not known whether the arranger was meant to preside over the entire album, the mix of orchestral and small group suits the leader just fine. Indeed, the small-group pieces hold their own among the orchestral pieces and do much to showcase Burrell’s musicality and versatility.

The album comes out swinging with Burrell in familiar territory, vamping on Elvin Jones’s absolutely Burrell-like “Downstairs.” Burrell is equally in his element on bassist Joe Benjamin’s “Terrace Theme” and the guitarist’s bossa-noverdrive number “Breadwinner,” all in a quintet with pianist Roger Kellaway, Benjamin on bass, Grady Tate on drums and Willie Rodriguez on congas.

The guitarist himself transcribed George Gershwin’s 1926 piece “Prelude #2” for solo acoustic guitar. It’s a particularly lovely, though brief, performance. The liner notes tell us that there was not enough space on the original album for the entire performance, so the recording was edited to offer up an “excerpt.” Strangely, though, when the disc was reissued on CD in 1997 with multiple takes of “Downstairs,” “Terrace Theme” and “Breadwinner,” there was no sign of an extended take of “Prelude #2” to be found.

As nicely balanced as this set is, the focus here is on the pieces Burrell performs with Gil Evans’s orchestra. Behind the scenes on these tracks are such luminaries as longtime Evans associates trumpeter Johnny Coles, trombonist Jimmy Cleveland and saxophonists Lee Konitz and Steve Lacy as well as such significant aides-de-camp as Richie Kamuca, Ron Carter and Elvin Jones.

None stand out as soloists here. But each serves Evans’s end to make his featured soloist sound, well, magnificent. The result is that Guitar Forms is as much a pleasure for fans of Kenny Burrell as Gil Evans. The five tracks covered here are the only five tracks listed in the recording logs. One could hope for more…but, well, dreams are just dreams.

First up is “Lotus Land.” Written in 1905 by British composer Cyrill Scott (1879-1970), “Louts Land” is clearly inspired by Asian harmonies, giving it an overtly exotic appeal. It is probably Scott’s best-known composition and its popularity is likely due to Martin Denny, who covered the tune on his 1957 “bachelor pad” classic, Exotica.

While pianist George Shearing covered “Lotus Land” in 1964, Kenny Burrell’s first brush with the song likely came during the September 1964 session he waxed for little-known pianist Eddie Bonnemère’s sole Prestige album Jazz Orient-ed.

Here, Burrell and Evans take “Lotus Land” outside of its Asian framing to more of a Spanish setting, obviously recalling Sketches of Spain. It’s an inspired reconsideration. Burrell takes the lead on acoustic guitar, while Evans propels with subtle flute and low-brass motifs. Burrell’s solo here always reminds me of the Flamenco piece played at the outset of John Barry’s Goldfinger (1964) score. But even at nine-plus minutes, this piece seems to fade as something more promising was yet to come.

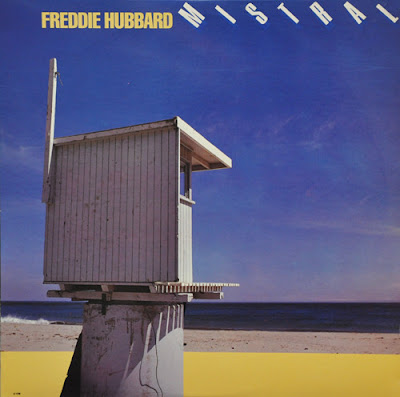

Alex Wilder’s “Moon and Sand” (1941) is a haunting ballad that hadn’t had much coverage in jazz in the mid-sixties. By the time Keith Jarrett recorded it in 1985, it was considered a “standard” and has since had much coverage, particularly among pianists.

Burrell had recorded the tune two months earlier with vocalist Pat Bowie on her Prestige album Out of Sight!, which is likely what gave the guitarist the idea to cover it here.

Burrell is on acoustic guitar while Evans provides a compelling bossa-nova framework, punctuated with impressionistic horn swaths. It’s a superb performance but producer Creed Taylor oddly brings the percussionists high up in the mix – suggesting some particularly aggressive waves washing up on those otherwise lovely shores.

Likely the inspiration behind Rudolph Legname’s Grammy-nominated cover photo, “Moon and Sand” stayed in the guitarist’s repertoire for many years. Indeed, Burrell recorded the song again in 1979 in a quartet setting – and with far more subtle percussion – for a lovely album called, what else, Moon and Sand.

Burrell’s “Loie” – written for his then-wife Dolores – originated on tenor saxophonist Ike Quebec’s 1962 Blue Note album Bossa Nova Soul Samba. Burrell also recorded a quartet version of “Loie” under his own name for Blue Note in 1963. That recording first appeared on a Japanese album called Freedom - issued in 1979 and reissued domestically on vinyl in 2011. That version of “Loie” can, however, be heard much more easily on the Blue Note compilation The Best of Kenny Burrell.

Here, again, Burrell beautifully leads on his acoustic axe. But Evans adds a fascinating sense of unease with oboe and some especially dramatic horn punctuations. There is, in this reading, an intriguing element of provocation: a love song gone awry. What could have been a jukebox jammer is, at least here, a tempest in a teapot. But it’s all the better for it.

Kenny Burrell had recorded “Greensleeves” with Coleman Hawkins in 1958 and Leo Wright in 1962, but the song was best known in jazz – then and now – from the John Coltrane Quartet’s bravura performance of the tune on the Creed Taylor-produced album Africa/Brass (1961).

The guitarist introduces “Greensleeves” on solo acoustic guitar before the orchestra rolls in and launches Burrell into his electric and positively electrical feature. Evans provides some of his finest big-band charts here since his Claude Thornhill days – while even foreshadowing the baroque charts Don Sebesky and others would provide to jazz players in the years to come.

Burrell would go on to record “Greensleeves” in trios with Jimmy Smith on the memorable Organ Grinder Swing (1965) and live on the otherwise forgotten Jazz Wave, Ltd: On Tour (1969).

Harold Arlen’s 1935 ballad “Last Night When We Were Young” is, perhaps, the album’s sleeper. The tune practically goes by without notice. It was a staple for Judy Garland, Tony Bennett and, perhaps most notably, Frank Sinatra. Burrell has long covered Arlen: “Get Happy,” for example, as well as “Out of this World,” “A Sleepin’ Bee,” “Blues in the Night,” “As Long as I Live” and “One for My Baby,” among others.

”Last Night” features some of Evans’s most subtle orchestrations. Indeed, they’re nearly negligible given Burrell’s acoustic performance of the tune. Evans’s contributions here are brief – but exceedingly memorable. He does what any good arranger is supposed to do: step back and make the leader sound good.

Guitar Forms was released in October 1965 with one single issued from the album, “Loie” backed with the Evans-less “Downstairs.” The disc was first issued on CD in 1985 (which is when I first heard it) and again in 1997 with four additional takes of “Downstairs” and “Breadwinner” and three additional takes of “Terrace Theme,” but nothing extra from the sessions with Evans.

The album was nominated for Best Instrumental Jazz Performance – Large Group or Soloist with Large Group – losing to Duke’s Ellington ‘66 – while Gil Evans’s arrangement of “Greensleeves” was nominated for Best Arrangement Accompanying Vocalist or Instrumentalist – losing to Gordon Jenkins’s arrangement of Frank Sinatra’s “It Was a Very Good Year.”

Guitar Forms is jazz at its classiest. The album stands out in Kenny Burrell’s extensive seventy-year discography as one of his best – which is saying something, given the sheer amount of good guitaring the man has waxed over that amazing amount of time. It is also ranks, to these ears, among the highlights of Gil Evans’s distinguished discography.

Burrell would go on to wax “arranged” albums with such greats as Richard Evans, Don Sebesky, Johnny Pate, Benny Golson and, much later, Gerald Wilson. But nothing comes close to the singular achievement that is Guitar Forms.