Following the surprise success of TV’s first jazz soundtrack, Peter Gunn (1959), the brilliant Henry Mancini (1924-94) could do no wrong. Indeed he surpassed the two particularly well conceived and performed soundtrack albums produced for the 1958-61 television show with a seemingly endless batch of music that was even more clever, more delightful and more timeless than Peter Gunn.

Following the surprise success of TV’s first jazz soundtrack, Peter Gunn (1959), the brilliant Henry Mancini (1924-94) could do no wrong. Indeed he surpassed the two particularly well conceived and performed soundtrack albums produced for the 1958-61 television show with a seemingly endless batch of music that was even more clever, more delightful and more timeless than Peter Gunn.During the early sixties, Mancini scored with great music from Mr. Lucky (1960), another jazz-oriented TV show, as well as a myriad of landmark film scores for High Time (1960, “The Second Time Around”), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961, “Moon River”), Experiment in Terror (1962), Hatari! (1962, “Baby Elephant Walk”), Days of Wine And Roses (1962 – although no soundtrack album was issued, the main theme still became a standard), Charade (1963), The Pink Panther (1963), A Shot In The Dark (1964, again no soundtrack album, though the main theme became a familiar staple of the Inspector Clouseau cartoons) and Arabesque (1966).

Mancini’s label, RCA also kept the composer/arranger busy in the studios, releasing one album after another of easy listening music – some focusing on the West Coast jazz light Mancini had single-handedly popularized and even more designed specifically for the upscale suburban market being courted by such space age popsters as Enoch Light, Percy Faith and Ferrante & Teicher. Even in the early sixties, Mancini released a near flawless collection of these non-soundtrack albums with such classics as The Mancini Touch (1960), The Blues And The Beat (1960), Combo! (1960), the essential Mr. Lucky Goes Latin (1962, with the original version of “Lujon”), Our Man In Hollywood (1963, featuring the “Days Of Wine And Roses” theme and a version of “Dreamsville” with lyrics), the big band Uniquely Mancini (1963) and Mancini Plays Mancini And Other Composers (1967, included here because this was the first place other than a 45 to get the theme to 1964’s A Shot In The Dark and the beautiful “The Shadows of Paris”).

By the late sixties, though, Mancini’s magical luster seemed to be waning. Prolific as ever, he waxed plenty of film soundtracks (The Great Race, What Did You Do During The War, Daddy?, Two For The Road, Gunn – Number One, The Party, Me, Natalie, Gaily, Gaily and Darling Lili, etc.), even more easy-listening and jazz-light records (the best of which are probably The Latin Sound of Henry Mancini, Mancini ’67 and The Big Latin Band of Henry Mancini) and still came up with a number of timeless classics. These all have their moments – and their fans – yet the sparkling musical wit and the lovely, lilting melodicism Mancini’s music had seemingly paled as the rock was dawning and a whole new generation of jazz-infused composers (Schifrin, Jones, Goldsmith, Fielding, Mandel, Legrand, etc.) made their stamp on Hollywood music.

By the late sixties, though, Mancini’s magical luster seemed to be waning. Prolific as ever, he waxed plenty of film soundtracks (The Great Race, What Did You Do During The War, Daddy?, Two For The Road, Gunn – Number One, The Party, Me, Natalie, Gaily, Gaily and Darling Lili, etc.), even more easy-listening and jazz-light records (the best of which are probably The Latin Sound of Henry Mancini, Mancini ’67 and The Big Latin Band of Henry Mancini) and still came up with a number of timeless classics. These all have their moments – and their fans – yet the sparkling musical wit and the lovely, lilting melodicism Mancini’s music had seemingly paled as the rock was dawning and a whole new generation of jazz-infused composers (Schifrin, Jones, Goldsmith, Fielding, Mandel, Legrand, etc.) made their stamp on Hollywood music.Mancini’s pace never slowed as the seventies dawned. But things had changed and his music – or the style of music he perfected to an artful craft – seemed hopelessly out of fashion. Undeterred, Mancini persevered. Embracing the “pop” music which came to be known as M.O.R. (middle of the road) he seemed to grasp the new sort of touchy-feely popular music as well as seize upon the film and TV themes of younger composers, who could also be considered the progeny of the mentor maestro, Henry Mancini.

This list details an overview of some of Henry Mancini’s more notable albums of the 1970s, a period of Mancini’s music that didn’t get a whole lot of critical – or popular – attention. Fans have their favorites – and mine will certainly become evident here – but it’s unlikely to find consideration of more than one or two albums of Mancini 70s records in one place and I wanted to take a look at the bigger picture…

Mancini Plays The Theme From Love Story (RCA, 1970): A collection of “movie music with the Mancini sound” worthwhile only for Mancini’s intriguing and otherwise unissued theme to The Night Visitor (beautifully covered by Jimmy Smith and Oliver Nelson on a 1971 45) and the equally disquieting “Theme For Three” (from Wait Until Dark), which had only been issued before as the b-side to a 45 of the film’s title song (the dazzling theme is called “Main Title” on the 2007 FSM CD of the Wait Until Dark soundtrack). The Love Story album also includes Mancini’s “Theme from ‘The Hawaiians’,” “Tomorrow Is My Friend” (from Gaily, Gaily), “Loss of Love” (from Sunflower) and “Whistling Away The Dark” (from Darling Lili) as well as snoozy covers of themes by Claude Bolling (“Borsalino”), Leslie Bricusse (“Thank You Very Much” from Scrooge) and Francis Lai’s eponymous hit. Mancini notably opts to cover Ennio Morricone’s unfamiliar, almost experimental “The Harmonica Man” (from Once Upon A Time In The West) and dresses up Johnny Mandel’s otherwise soapy “Song from ‘M*A*S*H’” (aka “Suicide is Painless”) with a dopey funk vibe that doesn’t help it sound any better than the original.

Mancini Plays The Theme From Love Story (RCA, 1970): A collection of “movie music with the Mancini sound” worthwhile only for Mancini’s intriguing and otherwise unissued theme to The Night Visitor (beautifully covered by Jimmy Smith and Oliver Nelson on a 1971 45) and the equally disquieting “Theme For Three” (from Wait Until Dark), which had only been issued before as the b-side to a 45 of the film’s title song (the dazzling theme is called “Main Title” on the 2007 FSM CD of the Wait Until Dark soundtrack). The Love Story album also includes Mancini’s “Theme from ‘The Hawaiians’,” “Tomorrow Is My Friend” (from Gaily, Gaily), “Loss of Love” (from Sunflower) and “Whistling Away The Dark” (from Darling Lili) as well as snoozy covers of themes by Claude Bolling (“Borsalino”), Leslie Bricusse (“Thank You Very Much” from Scrooge) and Francis Lai’s eponymous hit. Mancini notably opts to cover Ennio Morricone’s unfamiliar, almost experimental “The Harmonica Man” (from Once Upon A Time In The West) and dresses up Johnny Mandel’s otherwise soapy “Song from ‘M*A*S*H’” (aka “Suicide is Painless”) with a dopey funk vibe that doesn’t help it sound any better than the original. The Mancini Generation (RCA, 1972): For the “soundtrack” to his brief-lived Lawrence Welk Show-like TV variety program, Henry Mancini returned to the big band sound he’d always favored but hadn’t recorded since Mancini ‘67 (earlier examples include 1960's The Blues And The Beat and 1963's Uniquely Mancini). Mancini’s intent here was to transcend musical generations, grafting contemporary arrangements on the classics and giving some classic big-band finesse to “today’s history makers.” Surprisingly, there are no pop or rock covers here nor any of the material from – or with – any of the show’s musical guests. The “classics” include Bach’s “Joy” (aka “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” which got a rock-ish hit recording by Apollo 100 in early 1972), “The Masterpiece” (or the Rondeau from "Symphonies and Fanfares for the King's Supper" by French composer Jean-Joseph Mouret – the theme that launched the PBS TV series Masterpiece Theatre in 1971) and a reverential reading of the traditional “Amazing Grace,” which seems hopelessly out of place here. As for the “newer” material, Mancini covers Herbie Mann’s “Memphis Underground” with adequately funky touches and Benny Golson’s otherwise inviting “Killer Joe” (made famous by Quincy Jones’ 1969 orchestral cover of it on CTI), surprisingly, as something of a novelty tune. The composer contributes a lively march-like swinger for the show’s main theme, a new take on “Charade” (which reveals its Count Basie inspiration here more than ever) and Gunn’s “A Bluish Bag,” a terrific little groover that benefits by Jerome Richardson’s hypnotic soprano solo. Unfortunately, the album isn’t terribly memorable and at 31 minutes, feels like less than a well-prepared program of material. But its chief appeal is the quality of arrangements that Mr. Mancini provides throughout. Mancini orchestrates some especially fine flute parts for “Memphis Underground” and, more notably, “The Masterpiece” – a sequence which prefigures the excellent flute break he conceived for his brilliant cover of Mike Post’s “The Rockford Files” several years later; probably a thematic ode to the flute lead of the album’s title track. Both “Charade” and “A Bluish Bag” have been reconsidered substantially here and sound quite different than they did in their original incarnations and Stan Kenton’s “Eager Beaver,” with Jimmie Rowles on Fender Rhodes and Victor Feldman on vibes is an excellent example of just how effectively Mancini was able to modernize the big band sound for a new generation of listeners. The Mancini Generation was a good idea that just didn’t work. Chances are, though, had there been more like “The Masterpiece,” “A Bluish Bag” or “Eager Beaver” here, this generation would have been more memorable.

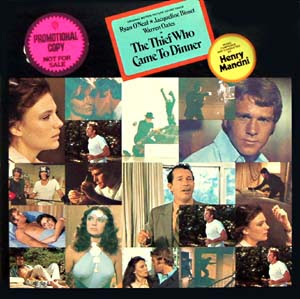

The Mancini Generation (RCA, 1972): For the “soundtrack” to his brief-lived Lawrence Welk Show-like TV variety program, Henry Mancini returned to the big band sound he’d always favored but hadn’t recorded since Mancini ‘67 (earlier examples include 1960's The Blues And The Beat and 1963's Uniquely Mancini). Mancini’s intent here was to transcend musical generations, grafting contemporary arrangements on the classics and giving some classic big-band finesse to “today’s history makers.” Surprisingly, there are no pop or rock covers here nor any of the material from – or with – any of the show’s musical guests. The “classics” include Bach’s “Joy” (aka “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” which got a rock-ish hit recording by Apollo 100 in early 1972), “The Masterpiece” (or the Rondeau from "Symphonies and Fanfares for the King's Supper" by French composer Jean-Joseph Mouret – the theme that launched the PBS TV series Masterpiece Theatre in 1971) and a reverential reading of the traditional “Amazing Grace,” which seems hopelessly out of place here. As for the “newer” material, Mancini covers Herbie Mann’s “Memphis Underground” with adequately funky touches and Benny Golson’s otherwise inviting “Killer Joe” (made famous by Quincy Jones’ 1969 orchestral cover of it on CTI), surprisingly, as something of a novelty tune. The composer contributes a lively march-like swinger for the show’s main theme, a new take on “Charade” (which reveals its Count Basie inspiration here more than ever) and Gunn’s “A Bluish Bag,” a terrific little groover that benefits by Jerome Richardson’s hypnotic soprano solo. Unfortunately, the album isn’t terribly memorable and at 31 minutes, feels like less than a well-prepared program of material. But its chief appeal is the quality of arrangements that Mr. Mancini provides throughout. Mancini orchestrates some especially fine flute parts for “Memphis Underground” and, more notably, “The Masterpiece” – a sequence which prefigures the excellent flute break he conceived for his brilliant cover of Mike Post’s “The Rockford Files” several years later; probably a thematic ode to the flute lead of the album’s title track. Both “Charade” and “A Bluish Bag” have been reconsidered substantially here and sound quite different than they did in their original incarnations and Stan Kenton’s “Eager Beaver,” with Jimmie Rowles on Fender Rhodes and Victor Feldman on vibes is an excellent example of just how effectively Mancini was able to modernize the big band sound for a new generation of listeners. The Mancini Generation was a good idea that just didn’t work. Chances are, though, had there been more like “The Masterpiece,” “A Bluish Bag” or “Eager Beaver” here, this generation would have been more memorable. The Thief Who Came To Dinner (Warner Bros., 1973) Henry Mancini’s soundtrack to this 1973 Bud Yorkin film starring Ryan O’Neal, Jacqueline Bisset and Warren Oates was one of his best in some years and the first of his truly memorable seventies scores. The comic caper film was a natural for the man who perfected this sort of thing years before with The Pink Panther, Charade, A Shot In The Dark and Arabesque. But, unlike John Barry, who was forced to produce one James Bond score after another even for non-James Bond films, Henry Mancini delivers something new, even unique here. While the mood is light, there is enough tension to underscore the suspense of the action (some of it recalling Lalo Schifrin’s own 1973 Warner Bros. soundtrack to Enter The Dragon) and it’s all delivered with an appropriately funky groove at the bottom. The fact is, Mancini hadn’t ever delivered this much rhythm in the rhythm section before. The excellent main theme stands alongside some of Mancini’s best “mystery” themes and, of course, is orchestrated to perfection by Mancini using some already dated sounds that sound perfectly sensible and contemporary in Mancini’s handling. The boogie woogie of “Tail Gate” boasts some of Mancini’s fantastic string and horn writing. The heist cues (“Dog Eat Dog,” “First Job,” “The Patter” and “The Really Big Heist”) mostly begin by launching off some riff of the film’s main theme into more exciting, jazz-like explorations that find Mancini at the top of his game. Mancini’s sparkling wit is much in evidence on the easy listening numbers here (“Love Them For Lauara,” “Jackie’s Theme,” “Soft Scene”) – giving them something of a nice seventies spin, which makes them essential listening for fans who want to hear the best of Mancini during this period. FSM did a typically outstanding job issuing The Thief Who Came To Dinner on CD in 2009 by including all 12 tracks of the original 1973 Warner Bros. album – which represented the actual music from the film – with 12 bonus tracks (totaling 18 minutes) of previously unissued music from the film plus three country source cues used in the movie and two demo themes recorded but not used. The FSM CD also contains superb detailed notes by Scott Bettencourt and Lukas Kendall which, as expected, makes for exceptionally fascinating reading. Most highly recommended.

The Thief Who Came To Dinner (Warner Bros., 1973) Henry Mancini’s soundtrack to this 1973 Bud Yorkin film starring Ryan O’Neal, Jacqueline Bisset and Warren Oates was one of his best in some years and the first of his truly memorable seventies scores. The comic caper film was a natural for the man who perfected this sort of thing years before with The Pink Panther, Charade, A Shot In The Dark and Arabesque. But, unlike John Barry, who was forced to produce one James Bond score after another even for non-James Bond films, Henry Mancini delivers something new, even unique here. While the mood is light, there is enough tension to underscore the suspense of the action (some of it recalling Lalo Schifrin’s own 1973 Warner Bros. soundtrack to Enter The Dragon) and it’s all delivered with an appropriately funky groove at the bottom. The fact is, Mancini hadn’t ever delivered this much rhythm in the rhythm section before. The excellent main theme stands alongside some of Mancini’s best “mystery” themes and, of course, is orchestrated to perfection by Mancini using some already dated sounds that sound perfectly sensible and contemporary in Mancini’s handling. The boogie woogie of “Tail Gate” boasts some of Mancini’s fantastic string and horn writing. The heist cues (“Dog Eat Dog,” “First Job,” “The Patter” and “The Really Big Heist”) mostly begin by launching off some riff of the film’s main theme into more exciting, jazz-like explorations that find Mancini at the top of his game. Mancini’s sparkling wit is much in evidence on the easy listening numbers here (“Love Them For Lauara,” “Jackie’s Theme,” “Soft Scene”) – giving them something of a nice seventies spin, which makes them essential listening for fans who want to hear the best of Mancini during this period. FSM did a typically outstanding job issuing The Thief Who Came To Dinner on CD in 2009 by including all 12 tracks of the original 1973 Warner Bros. album – which represented the actual music from the film – with 12 bonus tracks (totaling 18 minutes) of previously unissued music from the film plus three country source cues used in the movie and two demo themes recorded but not used. The FSM CD also contains superb detailed notes by Scott Bettencourt and Lukas Kendall which, as expected, makes for exceptionally fascinating reading. Most highly recommended. Hangin’ Out With Henry Mancini (RCA, 1974): This eclectic collection combines several instrumental pop covers of the day with a rag-tag assortment of mostly unremarkable film themes. Mancini’s covers of “Love’s Theme/TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia),” “The Entertainer” and “The Stripper” (famed at the time for use in a Noxema commercial) depart surprisingly little from their original instrumental incarnations, though Mancini offers a nice string break to “The Entertainer” which gives it some of the personality the other covers lack and American reed player Don Menza, back from a long stay in Europe, delivers a delicious solo in “TSOP.” Hangin’ Out also features otherwise unissued Mancini film themes from The Girl From Petrovka, the beautiful The White Dawn and 99 and 44/100% Dead (the bawdy/goofy title track) and a recording of “The Thief Who Came To Dinner” (also issued on 45) with a wordless chorus of eight voices as Mancini intended to use for the film but did not. Mancini’s piano is in the foreground of the ballad covers of Andre Popp’s “Song For Anna,” Francis Lai’s “The Sex Symbol” (surprisingly, one of the 45s released from this album) and Milton di Sao Paulo’s little-known 1974 hit “Dolce.” But unlike 1969’s A Warm Shade of Ivory, it’s not enough to hang on to and as a whole, the album lacks that typical Mancini personality. Highlights: the otherwise limited availability of the “Theme from The White Dawn” and the provocative alternative version of the funkier-than-the-rest-of-this-stuff “The Thief Who Came To Dinner.”

Hangin’ Out With Henry Mancini (RCA, 1974): This eclectic collection combines several instrumental pop covers of the day with a rag-tag assortment of mostly unremarkable film themes. Mancini’s covers of “Love’s Theme/TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia),” “The Entertainer” and “The Stripper” (famed at the time for use in a Noxema commercial) depart surprisingly little from their original instrumental incarnations, though Mancini offers a nice string break to “The Entertainer” which gives it some of the personality the other covers lack and American reed player Don Menza, back from a long stay in Europe, delivers a delicious solo in “TSOP.” Hangin’ Out also features otherwise unissued Mancini film themes from The Girl From Petrovka, the beautiful The White Dawn and 99 and 44/100% Dead (the bawdy/goofy title track) and a recording of “The Thief Who Came To Dinner” (also issued on 45) with a wordless chorus of eight voices as Mancini intended to use for the film but did not. Mancini’s piano is in the foreground of the ballad covers of Andre Popp’s “Song For Anna,” Francis Lai’s “The Sex Symbol” (surprisingly, one of the 45s released from this album) and Milton di Sao Paulo’s little-known 1974 hit “Dolce.” But unlike 1969’s A Warm Shade of Ivory, it’s not enough to hang on to and as a whole, the album lacks that typical Mancini personality. Highlights: the otherwise limited availability of the “Theme from The White Dawn” and the provocative alternative version of the funkier-than-the-rest-of-this-stuff “The Thief Who Came To Dinner.” The Return Of The Pink Panther (RCA, 1975): It had been eleven years since Blake Edwards’ previous Pink Panther film and this one, the third link in the chain, reportedly began life as a British TV series that never happened. Fortunately, the series’ three primaries – writer/director Blake Edwards, actor Peter Sellers as Inspector Clouseau and, of course, composer Henry Mancini – all returned to make what many consider to be the best film in the entire series, a series which ended in 1993 upon the death of perhaps its most important contributor, Henry Mancini. The animated title sequence is also among the very best in the entire series, scored by Mancini with a new true-to-the-original rendition of “The Pink Panther Theme” featuring the tenor sax of Tony Coe (in place of original Panther saxist Plas Johnson) and the uncredited trombone antics of (probably) Dick Nash. The film’s bravura sequence is surely the well-executed heist of the Pink Panther diamond from a Moroccan museum (why Morocco?). In a nice tribute to Hitchcock’s To Catch A Thief, the crime is allegedly committed by “The Phantom” (Sir Charles Litton, a role originated by David Niven, played here by Christopher Plummer). But the ten-minute sequence, put together marvelously by director Edwards and editor Tom Priestly, benefits by two of Henry Mancini’s strongest caper cues ever, here given the combined title “The Return of The Pink Panther, Part 1 and II.” Part one of the 5-minute and 12-second cue is Mancini’s elegant processional, contrasting the burglar’s professionalism and craftsmanship with the complicit viewer’s tension and anxiety. Part two is Mancini’s gloriously clever “chase music” as the heister successfully flees the museum guards (with guns!) in an Olympian flight through the museum and over the rooftops of the Morrocan night. Surprisingly, Mancini is not ashamed to deliver some of the cocktail music here that made the first Pink Panther film such a hit at the cinema and in record stores some dozen years before. Not surprisingly, though, the light stuff is remarkably well-conceived. Each is perfectly melodic and developed with a full sense of drama that can’t be appreciated as background music to a film – making a soundtrack album like this essential. The cocktail numbers are plentiful and include “The Greatest Gift” (the thoroughly anachronistic vocal version actually plays as a source cue in what is supposed to be a trendy disco!), “Here’s Looking At You, Kid,” the spritely “Summer in Gstaad” (which recalls earlier Mancini exotica like “Cortina” and “Mégève”), “So Smooth” and the lovely near samba of “Dreamy” (featuring Mancini leading, well, dreamily on piano atop the composer’s gorgeously arranged bed of strings). The remainder of the brief 33-minute soundtrack finds Mancini in top form with two appropriately, pardon the pun, Arabesque titles (“Naval Maneuver” and “Belly Belly Bum Bum”), one rockish piece called “Disco” (as it plays in the discotheque where the disguised Clouseau finds and “picks up” Lady Litton) and two Basie-like jazz numbers, “The Orange Float” and “The Wet Look” that both get excellent, compact solos by the unnamed electric piano, flute and vibes players. Highly recommended.

The Return Of The Pink Panther (RCA, 1975): It had been eleven years since Blake Edwards’ previous Pink Panther film and this one, the third link in the chain, reportedly began life as a British TV series that never happened. Fortunately, the series’ three primaries – writer/director Blake Edwards, actor Peter Sellers as Inspector Clouseau and, of course, composer Henry Mancini – all returned to make what many consider to be the best film in the entire series, a series which ended in 1993 upon the death of perhaps its most important contributor, Henry Mancini. The animated title sequence is also among the very best in the entire series, scored by Mancini with a new true-to-the-original rendition of “The Pink Panther Theme” featuring the tenor sax of Tony Coe (in place of original Panther saxist Plas Johnson) and the uncredited trombone antics of (probably) Dick Nash. The film’s bravura sequence is surely the well-executed heist of the Pink Panther diamond from a Moroccan museum (why Morocco?). In a nice tribute to Hitchcock’s To Catch A Thief, the crime is allegedly committed by “The Phantom” (Sir Charles Litton, a role originated by David Niven, played here by Christopher Plummer). But the ten-minute sequence, put together marvelously by director Edwards and editor Tom Priestly, benefits by two of Henry Mancini’s strongest caper cues ever, here given the combined title “The Return of The Pink Panther, Part 1 and II.” Part one of the 5-minute and 12-second cue is Mancini’s elegant processional, contrasting the burglar’s professionalism and craftsmanship with the complicit viewer’s tension and anxiety. Part two is Mancini’s gloriously clever “chase music” as the heister successfully flees the museum guards (with guns!) in an Olympian flight through the museum and over the rooftops of the Morrocan night. Surprisingly, Mancini is not ashamed to deliver some of the cocktail music here that made the first Pink Panther film such a hit at the cinema and in record stores some dozen years before. Not surprisingly, though, the light stuff is remarkably well-conceived. Each is perfectly melodic and developed with a full sense of drama that can’t be appreciated as background music to a film – making a soundtrack album like this essential. The cocktail numbers are plentiful and include “The Greatest Gift” (the thoroughly anachronistic vocal version actually plays as a source cue in what is supposed to be a trendy disco!), “Here’s Looking At You, Kid,” the spritely “Summer in Gstaad” (which recalls earlier Mancini exotica like “Cortina” and “Mégève”), “So Smooth” and the lovely near samba of “Dreamy” (featuring Mancini leading, well, dreamily on piano atop the composer’s gorgeously arranged bed of strings). The remainder of the brief 33-minute soundtrack finds Mancini in top form with two appropriately, pardon the pun, Arabesque titles (“Naval Maneuver” and “Belly Belly Bum Bum”), one rockish piece called “Disco” (as it plays in the discotheque where the disguised Clouseau finds and “picks up” Lady Litton) and two Basie-like jazz numbers, “The Orange Float” and “The Wet Look” that both get excellent, compact solos by the unnamed electric piano, flute and vibes players. Highly recommended. Soul Symphony (RCA, 1975): Quite simply, Soul Symphony is one of the two or three best – if not the best – Henry Mancini album of the seventies. There is little doubt that Mancini’s brand of music might have seemed old fashioned or hopelessly out of date by 1975. Surely at this point, most of the other “space age” popsters Mancini came up with during the fifties and sixties had faded into obscurity because of their failure or lack of interest to keep up with the times. It might have also been the increasing musical apathy of the fan base’s aging audience (which found new life among crate diggers some two decades later). But unlike nearly all the others, Mancini transcended all of that to produce one of the coolest middle-of-the-road (MOR) albums of the day. Start with the rhythm section. Mancini collected some of the very best of the young West Coast jazz players/soloists, including (Crusader) Joe Sample on keyboards, Abraham Laboriel on bass, Harvey Mason on drums, Dennis Budimer, Lee Ritenour and David T. Walker on guitars and Mayuto, Dale Anderson and Emil Richards on percussion. Then there’s the program. Mancini composed the dynamic title track for the occasion and significantly updated two of his classics, “Peter Gunn” (this was the version featured on his A Legendary Performer album issued a few years later) and “Slow Hot Wind” (a complete revamp of the great “Lujon” from Mr. Lucky Goes Latin). The remaining six tracks are among some of the best covers Mancini has ever chosen for one album: Herbie Hancock’s beautiful “Butterfly” (originally from the keyboardist’s exceptional album Thrust), Barry White’s “Satin Soul” (originally from the Love Unlimited Orchestra’s second album White Gold), “Pick Up The Pieces” (the excellent funk classic from the Australian Average White Band’s first album), “Sun Goddess” (originally from the Ramsey Lewis album of the same name), the weird but funky “Soul Saga” (originally from Quincy Jones’s Body Heat album) and Van McCoy’s “African Symphony” (from the composer’s pre-“The Hustle” album Love Is The Answer). Mancini’s outstanding arrangements are much in evidence and he allows plenty of improvisation over the near jazz fusion tunes by trumpeter Bud Brisbois, bassist Abraham Laboriel, keyboardist Joe Sample, Louise DiTullio (“Slow Hot Wind”), harmonica player Tommy Morgan (“Soul Saga”) and Mayuto on the kalimba (“African Symphony”). Outstanding throughout and an essential part of any Henry Mancini collection.

Soul Symphony (RCA, 1975): Quite simply, Soul Symphony is one of the two or three best – if not the best – Henry Mancini album of the seventies. There is little doubt that Mancini’s brand of music might have seemed old fashioned or hopelessly out of date by 1975. Surely at this point, most of the other “space age” popsters Mancini came up with during the fifties and sixties had faded into obscurity because of their failure or lack of interest to keep up with the times. It might have also been the increasing musical apathy of the fan base’s aging audience (which found new life among crate diggers some two decades later). But unlike nearly all the others, Mancini transcended all of that to produce one of the coolest middle-of-the-road (MOR) albums of the day. Start with the rhythm section. Mancini collected some of the very best of the young West Coast jazz players/soloists, including (Crusader) Joe Sample on keyboards, Abraham Laboriel on bass, Harvey Mason on drums, Dennis Budimer, Lee Ritenour and David T. Walker on guitars and Mayuto, Dale Anderson and Emil Richards on percussion. Then there’s the program. Mancini composed the dynamic title track for the occasion and significantly updated two of his classics, “Peter Gunn” (this was the version featured on his A Legendary Performer album issued a few years later) and “Slow Hot Wind” (a complete revamp of the great “Lujon” from Mr. Lucky Goes Latin). The remaining six tracks are among some of the best covers Mancini has ever chosen for one album: Herbie Hancock’s beautiful “Butterfly” (originally from the keyboardist’s exceptional album Thrust), Barry White’s “Satin Soul” (originally from the Love Unlimited Orchestra’s second album White Gold), “Pick Up The Pieces” (the excellent funk classic from the Australian Average White Band’s first album), “Sun Goddess” (originally from the Ramsey Lewis album of the same name), the weird but funky “Soul Saga” (originally from Quincy Jones’s Body Heat album) and Van McCoy’s “African Symphony” (from the composer’s pre-“The Hustle” album Love Is The Answer). Mancini’s outstanding arrangements are much in evidence and he allows plenty of improvisation over the near jazz fusion tunes by trumpeter Bud Brisbois, bassist Abraham Laboriel, keyboardist Joe Sample, Louise DiTullio (“Slow Hot Wind”), harmonica player Tommy Morgan (“Soul Saga”) and Mayuto on the kalimba (“African Symphony”). Outstanding throughout and an essential part of any Henry Mancini collection. The Cop Show Themes (RCA, 1976): Another excellent Mancini collection with a perfectly timely theme. Cop shows pervaded television during the mid seventies and a staggeringly high percentage of these had memorable, timeless themes. Mancini covers quite a few of them here, and most would be very well known to anyone watching TV at the time, though one might wish for others as well (Lalo Schifrin’s “Mannix,” Tom Scott’s “Starsky & Hutch” and Jerry Goldsmith’s “Barnaby Jones” or “Police Story,” would be welcome for the Mancini treatment). Mancini offers his own themes for The NBC Mystery Movie (the familiar “Mystery Movie Theme,” an umbrella theme used during 1971-77 for the rotating presentation of such series as Columbo, McCloud, McMillian & Wife, Banacek and Quincy, M.E. - already featured on Mancini’s 1972 album Big Screen Little Screen) and the short-lived The Blue Knight (“Bumper’s Theme,” starring George Kennedy as Bumper). But Mancini’s aren’t the best themes represented here. What he does with other people’s catchy cop show themes is nearly miraculous and with a typically good cast of studio jazz guys to spice it up, most of the album delivers the usual suspects with a dose of high quality musicianship. Indeed, it was only on albums like this where you could hear a lot of these themes – and they do sound quite good together. Mancini beautifully covers Patrick Williams’ brilliant “The Streets of San Francisco” (featuring Artie Kane on electric piano), a medley of Billy Goldenberg’s “Kojak” and Barry DeVorzon’s tremendous and popular “S.W.A.T.” (featuring a great Mancini bumblebee string arrangement, Abraham Laboriel on bass, Graham Young on trumpet and Lee Ritenour on guitar), Mort Stevens’s definitive “Hawaii Five-O” (featuring Dick Nash on trombone) and the equally enigmatic but less known “Police Woman” (showing off how well Mancini can spar horns with strings). While the entire album is exceptionally good, Mancini’s takes on Dave Grusin’s “Baretta’s Theme” and Mike Post’s “The Rockford Files” – both outstanding compositions in their original form – are especially well conceived here. “Baretta’s Theme” gets a superb funk arrangement by Mancini, highlighted by Artie Kane’s beautiful Grusin quotes (right out of Three Days of the Condor). Abraham Laboriel’s bass pretty much drives the whole song, while Don Menza on flute trades solo licks with Oscar Brashear on trumpet. Notably, Mancini’s version of “Baretta” includes Lee Ritenour and Harvey Mason, who were both probably heard on Grusin’s original. Mancini’s remarkable take on “The Rockford Files” is probably the album’s single most significant moment. Mancini brilliantly rescores this song as a funky piece of baroque music, signaled by Artie Kane’s opening use of harpsichord, a mellifluous string section stating the melody (which makes the song sound less awkward than Post’s original) and Mancini’s own addition of a luminous, goose-bump inducing flute counter melody. Don Menza offers a soaring, melodious solo on tenor sax, buffered by Dennis Budimer’s rock guitar and Mancini’s supple string counterpoint. By the time the horn section enters with its triumphant refrain, Mancini has developed a magnificently dramatic piece of music out of Post’s mere TV theme that could be considered a modern concerto of melodic funk. Even if the rest of the album were forgettable (and it isn’t), “Baretta’s Theme” and “The Rockford Files” make The Cop Show Themes absolutely essential.

The Cop Show Themes (RCA, 1976): Another excellent Mancini collection with a perfectly timely theme. Cop shows pervaded television during the mid seventies and a staggeringly high percentage of these had memorable, timeless themes. Mancini covers quite a few of them here, and most would be very well known to anyone watching TV at the time, though one might wish for others as well (Lalo Schifrin’s “Mannix,” Tom Scott’s “Starsky & Hutch” and Jerry Goldsmith’s “Barnaby Jones” or “Police Story,” would be welcome for the Mancini treatment). Mancini offers his own themes for The NBC Mystery Movie (the familiar “Mystery Movie Theme,” an umbrella theme used during 1971-77 for the rotating presentation of such series as Columbo, McCloud, McMillian & Wife, Banacek and Quincy, M.E. - already featured on Mancini’s 1972 album Big Screen Little Screen) and the short-lived The Blue Knight (“Bumper’s Theme,” starring George Kennedy as Bumper). But Mancini’s aren’t the best themes represented here. What he does with other people’s catchy cop show themes is nearly miraculous and with a typically good cast of studio jazz guys to spice it up, most of the album delivers the usual suspects with a dose of high quality musicianship. Indeed, it was only on albums like this where you could hear a lot of these themes – and they do sound quite good together. Mancini beautifully covers Patrick Williams’ brilliant “The Streets of San Francisco” (featuring Artie Kane on electric piano), a medley of Billy Goldenberg’s “Kojak” and Barry DeVorzon’s tremendous and popular “S.W.A.T.” (featuring a great Mancini bumblebee string arrangement, Abraham Laboriel on bass, Graham Young on trumpet and Lee Ritenour on guitar), Mort Stevens’s definitive “Hawaii Five-O” (featuring Dick Nash on trombone) and the equally enigmatic but less known “Police Woman” (showing off how well Mancini can spar horns with strings). While the entire album is exceptionally good, Mancini’s takes on Dave Grusin’s “Baretta’s Theme” and Mike Post’s “The Rockford Files” – both outstanding compositions in their original form – are especially well conceived here. “Baretta’s Theme” gets a superb funk arrangement by Mancini, highlighted by Artie Kane’s beautiful Grusin quotes (right out of Three Days of the Condor). Abraham Laboriel’s bass pretty much drives the whole song, while Don Menza on flute trades solo licks with Oscar Brashear on trumpet. Notably, Mancini’s version of “Baretta” includes Lee Ritenour and Harvey Mason, who were both probably heard on Grusin’s original. Mancini’s remarkable take on “The Rockford Files” is probably the album’s single most significant moment. Mancini brilliantly rescores this song as a funky piece of baroque music, signaled by Artie Kane’s opening use of harpsichord, a mellifluous string section stating the melody (which makes the song sound less awkward than Post’s original) and Mancini’s own addition of a luminous, goose-bump inducing flute counter melody. Don Menza offers a soaring, melodious solo on tenor sax, buffered by Dennis Budimer’s rock guitar and Mancini’s supple string counterpoint. By the time the horn section enters with its triumphant refrain, Mancini has developed a magnificently dramatic piece of music out of Post’s mere TV theme that could be considered a modern concerto of melodic funk. Even if the rest of the album were forgettable (and it isn’t), “Baretta’s Theme” and “The Rockford Files” make The Cop Show Themes absolutely essential. Mancini’s Angels (RCA, 1977): Similar in concept to Mancini’s 1972 album Big Screen Little Screen, Mancini’s Angels finds the composer/arranger tackling both film and TV themes of the day – surprisingly using one of the only “cheesecake” shots ever featured on a Mancini LP cover. Mancini offers his own cartoony “The Inspector Clouseau Theme” (from the film The Pink Panther Strikes Again and not “A Shot In The Dark,” which many of the Pink Panther cartoon watchers will consider the real Inspector Clouseau theme), the unexceptional “Silver Streak” theme (from the 1976 film whose soundtrack wasn’t issued until 2002 by Intrada), the goofy “What’s Happening!! Theme” and the little-known theme to an-star TV mini-series called “The Moneychangers” (broadcast in December 1976). Mancini also boards the inevitable disco train here for his covers of the well-known themes from Charlie’s Angels (as the original version had not been previously issued, Mancini’s cover was one of the 45s released from the album), Car Wash and a fairly inventive take on Rocky (“Gonna Fly Now,” featuring a nice electric piano solo from Ralph Grierson). The long Roots suite (“Many Rains Ago (Oluwa)/Theme From Roots”) sounds pretty good in Mancini’s hands and only slightly less ponderous than the originals, while Barbra Streisand’s “Evergreen” (from A Star Is Born) benefits by a sensitive piano solo performed by Mancini himself. Hardly a classic, Mancini’s Angels is worthwhile for the otherwise unavailable themes to “What’s Happening!!” and “The Moneychangers” as well as the somewhat interesting way Mancini handles “Gonna Fly Now” and “Music from Roots” only.

Mancini’s Angels (RCA, 1977): Similar in concept to Mancini’s 1972 album Big Screen Little Screen, Mancini’s Angels finds the composer/arranger tackling both film and TV themes of the day – surprisingly using one of the only “cheesecake” shots ever featured on a Mancini LP cover. Mancini offers his own cartoony “The Inspector Clouseau Theme” (from the film The Pink Panther Strikes Again and not “A Shot In The Dark,” which many of the Pink Panther cartoon watchers will consider the real Inspector Clouseau theme), the unexceptional “Silver Streak” theme (from the 1976 film whose soundtrack wasn’t issued until 2002 by Intrada), the goofy “What’s Happening!! Theme” and the little-known theme to an-star TV mini-series called “The Moneychangers” (broadcast in December 1976). Mancini also boards the inevitable disco train here for his covers of the well-known themes from Charlie’s Angels (as the original version had not been previously issued, Mancini’s cover was one of the 45s released from the album), Car Wash and a fairly inventive take on Rocky (“Gonna Fly Now,” featuring a nice electric piano solo from Ralph Grierson). The long Roots suite (“Many Rains Ago (Oluwa)/Theme From Roots”) sounds pretty good in Mancini’s hands and only slightly less ponderous than the originals, while Barbra Streisand’s “Evergreen” (from A Star Is Born) benefits by a sensitive piano solo performed by Mancini himself. Hardly a classic, Mancini’s Angels is worthwhile for the otherwise unavailable themes to “What’s Happening!!” and “The Moneychangers” as well as the somewhat interesting way Mancini handles “Gonna Fly Now” and “Music from Roots” only. The Theme Scene (RCA, 1978): Like the previous year’s tepid Mancini’s Angels, The Theme Scene continues Mancini’s now well-known (and probably expected) tradition of film and TV theme albums. This too is a mostly bland and rather unnecessary review of such TV themes as Battlestar Galactica (Stu Phillips), Star Trek (Alexander Courage), Fantasy Island (which sounds so exotically otherworldly it could have come from “Star Trek!”), the dreadful Three’s Company (Don Nicholl/Joe Raposo – done up like one of Mancini’s own lounge themes from the early sixties) and the disposable Little House on the Prairie (David Rose). Also included here are film themes from the little-known The Children of Sanchez (Chuck Mangione), Heaven Can Wait (Dave Grusin), The Cheap Detective (Patrick Williams) done also, for the most part, just as tepidly. Mancini’s own “NBC Nightly New Theme” and “Once Is Not Enough” – neither of which are featured elsewhere – are included here. This one has the slight edge over Mancini’s Angels for the preferable melodic choices Mancini makes here. There is less – much less – concession to fashion here, which means, of course, disco rarely rears its overbearing head, and more of an effort to make one of those light Mancini albums of yore. One can only imagine how that might have gone over in 1978! Still, Mancini’s otherwise unavailable and un-newsy like “NBC Nightly New Theme” and the ultra lounge-y “Once Is Not Enough” (from Mancini’s score to the 1975 film based on a Jacqueline Susann novel) are worth hearing. Mancini’s relaxed, after-hours take on “The Cheap Detective” makes for some rather elegant late-night listening too. Something about the The Theme Scene’s utter lack of artistic and commercial success suggests the end of the road for this kind of album and this sort of music. Was this the end? Sure enough, Mancini receded into the occasional soundtrack album and “pops” covers of his old hits after this.

The Theme Scene (RCA, 1978): Like the previous year’s tepid Mancini’s Angels, The Theme Scene continues Mancini’s now well-known (and probably expected) tradition of film and TV theme albums. This too is a mostly bland and rather unnecessary review of such TV themes as Battlestar Galactica (Stu Phillips), Star Trek (Alexander Courage), Fantasy Island (which sounds so exotically otherworldly it could have come from “Star Trek!”), the dreadful Three’s Company (Don Nicholl/Joe Raposo – done up like one of Mancini’s own lounge themes from the early sixties) and the disposable Little House on the Prairie (David Rose). Also included here are film themes from the little-known The Children of Sanchez (Chuck Mangione), Heaven Can Wait (Dave Grusin), The Cheap Detective (Patrick Williams) done also, for the most part, just as tepidly. Mancini’s own “NBC Nightly New Theme” and “Once Is Not Enough” – neither of which are featured elsewhere – are included here. This one has the slight edge over Mancini’s Angels for the preferable melodic choices Mancini makes here. There is less – much less – concession to fashion here, which means, of course, disco rarely rears its overbearing head, and more of an effort to make one of those light Mancini albums of yore. One can only imagine how that might have gone over in 1978! Still, Mancini’s otherwise unavailable and un-newsy like “NBC Nightly New Theme” and the ultra lounge-y “Once Is Not Enough” (from Mancini’s score to the 1975 film based on a Jacqueline Susann novel) are worth hearing. Mancini’s relaxed, after-hours take on “The Cheap Detective” makes for some rather elegant late-night listening too. Something about the The Theme Scene’s utter lack of artistic and commercial success suggests the end of the road for this kind of album and this sort of music. Was this the end? Sure enough, Mancini receded into the occasional soundtrack album and “pops” covers of his old hits after this.  Who Is Killing The Great Chefs Of Europe? (Epic, 1978): Mancini’s orchestral score – recorded not in Hollywood but in England, which was what many of the Hollywood composers, including former Mancini pianist John Williams, were doing at the time – to a forgotten 1978 movie directed by Ted Kotcheff (First Blood, Weekend At Bernie’s) starring George Segal, Jacqueline Bisset and Robert Morley features many fine musical moments. Nothing funky or particularly lounge-y. This is simply the work of a magnificent composer doing what he does best, what is right for the film and coming up with a light-hearted score in the classic Hollywood tradition; something John Williams made de rigueur (again!) for Hollywood films following his ultra-popular scores to Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Superman. Highlights here include the lovely “Natasha’s Theme” (with a piano solo by Henry Mancini himself – which gets slightly altered variations in “Bombe Richelieu,” “Natasha in Venice” and the “End Title”), the charming and delightfully scored “Pesce!” (Italian for “fish!”) and the baroque – though comic – march of the main title theme (recalling Mancini’s love of Sousa and the score to the 1975 film The Great Waldo Pepper), also heard in several variations. The eating cues (“The Moveable Feast,” “The Gathering” and “The Final Feast”) all have a comic edge that sound like something Mancini would have done in the fifties. Clearly he relishes doing it here again, a whole generation later. Not essential (only “Natasha’s Theme” is memorable), but fun nonetheless.

Who Is Killing The Great Chefs Of Europe? (Epic, 1978): Mancini’s orchestral score – recorded not in Hollywood but in England, which was what many of the Hollywood composers, including former Mancini pianist John Williams, were doing at the time – to a forgotten 1978 movie directed by Ted Kotcheff (First Blood, Weekend At Bernie’s) starring George Segal, Jacqueline Bisset and Robert Morley features many fine musical moments. Nothing funky or particularly lounge-y. This is simply the work of a magnificent composer doing what he does best, what is right for the film and coming up with a light-hearted score in the classic Hollywood tradition; something John Williams made de rigueur (again!) for Hollywood films following his ultra-popular scores to Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Superman. Highlights here include the lovely “Natasha’s Theme” (with a piano solo by Henry Mancini himself – which gets slightly altered variations in “Bombe Richelieu,” “Natasha in Venice” and the “End Title”), the charming and delightfully scored “Pesce!” (Italian for “fish!”) and the baroque – though comic – march of the main title theme (recalling Mancini’s love of Sousa and the score to the 1975 film The Great Waldo Pepper), also heard in several variations. The eating cues (“The Moveable Feast,” “The Gathering” and “The Final Feast”) all have a comic edge that sound like something Mancini would have done in the fifties. Clearly he relishes doing it here again, a whole generation later. Not essential (only “Natasha’s Theme” is memorable), but fun nonetheless. ”10” (Warner Bros., 1979): Blake Edwards’ one-note romantic comedy “10” was quite a hit in its day and, more surprisingly, Mancini’s performance of French composer Maurice Ravel’s “Bolero,” featured in the film, became a huge hit too, making it one of those all-time iconic classical pieces that Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna” or Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” had become. The piece, titled “Ravel’s Bolero” here, is the centerpiece of the silly film’s unexpectedly terrible soundtrack album, even though – like an afterthought – it is the album’s final track. Otherwise, the soundtrack is a strange and unsatisfying mix of horridly corny ballads (“It’s Easy To Say,” a duet between the film’s stars, Julie Andrews and a very hammy Dudley Moore, the jokey Peter Sellers-like “I Have An Ear For Love,” sung by “The Reverend,” and the really awful “He Pleases Me,” sung straight by Ms. Andrews), overly sentimental background Muzak (“Something For Jenny,” two takes of “Don’t Call It Love” and two more takes of “It’s Easy To Say”) and strange disco funk (the perky “Keyboard Harmony” and the surprisingly clumsy “Get It On”). It’s hard to say why nothing really adds up here. Perhaps the magic of the long and successful collaboration of director Edwards and composer Mancini had finally run out of steam (though it revved back up again several years later with Victor/Victoria). Following three Pink Panther movies in a row (each one progressively worse than the one before), Edwards would seem to have loved the idea of getting away from Clouseau. Even Mancini would seemingly celebrate the opportunity to work outside of the Panther straight jacket. But no. Indeed this album plays like one of the lesser Panther soundtracks (The Pink Panther Strikes Again springs to mind). One especially notable oddity here is that, unlike nearly all of Mancini’s other film scores, the composer opted (or was forced?) to use another composer’s piece as the centerpiece of the film. Even the rest of the score has absolutely nothing to do with this piece – in timbre, melody, sound, structure, consideration, anything. It’s as if the rest of the music is completely divorced from what became its main theme, something which might be tolerable if the rest of the album was notable in some regard other than mere camp appeal (Mancini’s 1981 score to the camp classic Mommie Dearest is imminently superior to the campy ”10” and worthy of more serious attention). Considering its popularity – at least at the time – this is surely one of Henry Mancini’s most disappointing soundtrack albums ever.

”10” (Warner Bros., 1979): Blake Edwards’ one-note romantic comedy “10” was quite a hit in its day and, more surprisingly, Mancini’s performance of French composer Maurice Ravel’s “Bolero,” featured in the film, became a huge hit too, making it one of those all-time iconic classical pieces that Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna” or Richard Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” had become. The piece, titled “Ravel’s Bolero” here, is the centerpiece of the silly film’s unexpectedly terrible soundtrack album, even though – like an afterthought – it is the album’s final track. Otherwise, the soundtrack is a strange and unsatisfying mix of horridly corny ballads (“It’s Easy To Say,” a duet between the film’s stars, Julie Andrews and a very hammy Dudley Moore, the jokey Peter Sellers-like “I Have An Ear For Love,” sung by “The Reverend,” and the really awful “He Pleases Me,” sung straight by Ms. Andrews), overly sentimental background Muzak (“Something For Jenny,” two takes of “Don’t Call It Love” and two more takes of “It’s Easy To Say”) and strange disco funk (the perky “Keyboard Harmony” and the surprisingly clumsy “Get It On”). It’s hard to say why nothing really adds up here. Perhaps the magic of the long and successful collaboration of director Edwards and composer Mancini had finally run out of steam (though it revved back up again several years later with Victor/Victoria). Following three Pink Panther movies in a row (each one progressively worse than the one before), Edwards would seem to have loved the idea of getting away from Clouseau. Even Mancini would seemingly celebrate the opportunity to work outside of the Panther straight jacket. But no. Indeed this album plays like one of the lesser Panther soundtracks (The Pink Panther Strikes Again springs to mind). One especially notable oddity here is that, unlike nearly all of Mancini’s other film scores, the composer opted (or was forced?) to use another composer’s piece as the centerpiece of the film. Even the rest of the score has absolutely nothing to do with this piece – in timbre, melody, sound, structure, consideration, anything. It’s as if the rest of the music is completely divorced from what became its main theme, something which might be tolerable if the rest of the album was notable in some regard other than mere camp appeal (Mancini’s 1981 score to the camp classic Mommie Dearest is imminently superior to the campy ”10” and worthy of more serious attention). Considering its popularity – at least at the time – this is surely one of Henry Mancini’s most disappointing soundtrack albums ever.

After watching "The White Dawn" and finding Mancini's score to be beautiful and fascinating, I did an immediate internet search for the soundtrack. I was disappointed to find no official LP got pressed. But there do seem to be a few tantalizing scraps to be found on scattered releases. Thanks for turning me on to one of those songs: "Theme from The White Dawn."

ReplyDeleteWow! Thanks for those great reviews. I too have been a huge fan of Symphonic Soul (which you call Soul Symphony for some reason). It's my favorite, but I actually do like The Mancini Generation too, mostly for all the reasons you stated, and even the shamefully short (about 24 minutes!) "The Cop Show Themes", which I also now have on CD.

ReplyDeleteBut where's a review of the excellent Visions of Eight (1973)?

ReplyDeleteVisions of Eight is reviewed here: http://dougpayne.blogspot.com/2009/11/more-mancini-in-seventies.html.

ReplyDeletePeter, for the best Mancini rendering available of The White Dawn, check out the 1976 "Suite from The White Dawn", 11 minutes long, originally from the excellent LP "Henry Mancini Conduct the London Symphony Orchestra in a Concert of Film Music". All the suites are available, re-released as Themes from The Godfather,etc; on iTunes at http://itunes.apple.com/us/album/symphonic-suite-from-the-white/id299627052?i=299627108

ReplyDelete