This one’s been in my head for a while now. But not this version. The Talking Heads’ original, which appeared on their great Speaking In Tongues album, is what keeps buzzing around my brain.

David Byrne’s incessant “What about the time, you were rollin’ over” haunts me for some reason (ok – the lyric sheet says “we were rollin’ over” – but it sounds like you to me – and you makes more sense in the song).

I saw the Talking Heads back in ’82 in Pittsburgh and it was memorable for many reasons. Jerry Harrison. Oh, my, Jerry Harrison. Bernie Worrell. Oh, god, Bernie Worrell. I sat right in front of drummer Chris Frantz’s parents, also Pittsburgh natives, like me. And the surprisingly imminent musical showmanship of David Byrne. The whole amazing show.

They did this one too. And it’s always stayed with me.

Oddly enough, the great gospel group The Staple Singers came out with a techno dance cover of “Slippery People” in 1984. I remember the album, Turning Point, on the CBS-distributed label, Private I, with the computer generated cover art (something that probably seemed cool or maybe just cheap in 1984). It all seemed weird and unbelievable. But it sounded great.

I think lead Head David Byrne, flying high at the time on the success of Jonathan Demme’s film of the great Heads show I saw a few years earlier, Stop Making Sense (the title derives from Byrne’s lyric to “Girlfriend is Better,” also originally from the Speaking In Tongues album), is doing something on the track. Bass? Guitar? He probably sings too. But Mavis Staples (b. 1939) sounds sublime here. So does the always memorable Roebuck "Pops" Staples (1914-2000) on the few audible bits he gets.

The Staple Singers' utterly soulful cover of “Slippery People” is worth hearing again. So here it is.

Saturday, August 29, 2009

Wednesday, August 26, 2009

The Master Touch

Un Uomo Da Rispettare, which translates as A Man To Respect, is a 1972 Italian-German co-production, directed by Michele Lupo and starring Kirk Douglas, Florinda Bolkan and Giulano Gemma. The film did not open in the United States until May 1974, but when it did it came out as the somewhat more action-oriented and strangely sexually titled The Master Touch. Probably no one here ever saw it.

Un Uomo Da Rispettare, which translates as A Man To Respect, is a 1972 Italian-German co-production, directed by Michele Lupo and starring Kirk Douglas, Florinda Bolkan and Giulano Gemma. The film did not open in the United States until May 1974, but when it did it came out as the somewhat more action-oriented and strangely sexually titled The Master Touch. Probably no one here ever saw it.In it, Steve (Kirk Douglas) is a master thief who, immediately upon being released from a three-year prison sentence, is approached by a Hamburg crime lord called Miller (Wolfgang Priess) to steal $1 million of premium payments from the International Insurance Company. Steve declines the offer since his previous turn at working for Miller is what landed him in jail in the first place. But Steve begins to plan the robbery on his own against the wishes of his wife, Anna (Florinda Bolkan). He enlists the aid of (rather oddly) a circus trapeze artist named Marco (Giulano Gemma) and plots a fool-proof way to rob the insurance company while diverting attention away from the fact that his is “the master touch” that pocketed the funds.

The film fascinates in what was then-current technology, much as Sidney Lumet’s The Anderson Tapes did the year before, and how an old-fashioned caper is not be outdone by mere new-fangled technology. A “master touch” is all it takes. But, like all caper films of note, particularly the existential caper films of Jean Pierre Melville or Henri Verneuil, a successful job never secures a successful end. The idea of doing something dangerous on your own against the more powerful people whose idea it was in the first place also has a neat Wall Street parallel in the brilliant yet little-known cable TV film Barbarians at the Gate (1993).

The film is rife with many beguiling moments, but is notable for several key elements. First of all, the actors are all pros at the top of their game. They not only convince you these people exist, but they make you care for what’s happening to them. Kirk Douglas is superb. He brings a gravity that only an old-school Hollywood actor can, playing his gentleman bandit (for the most part) with a twinkle in his eye and some tears that can’t be seen. The beautiful Florinda Bolkan, who has the thankless role as “the woman” or the “long-suffering wife” here, is magnificent as always; saying more in a glance or a look than her excellent command of English ever could. She is, to my mind, one of cinema’s finest actresses but her choice of many genre parts – all of which she plays with tremendous aplomb – has probably unfairly marginalized her from serious consideration as a great artist.

Like Bolkan, other strong genre regulars inhabit the seemingly seedy film such as Wolfgang Priess (The Bloodstained Butterfly, The Fifth Cord) as the crime boss Miller, Romano Puppo (Street Law, The Big Racket, Gangbuster) as Miller’s henchman and character favorite Bruno Corazzari (Seven Blood Stained Orchids, Puzzle, The Cynic The Rat and The Fist) as Eric, the Stan (John Cazale) from The Conversation-like electronics expert who provides Steve with his gear.

Undoubtedly, however, one of the most memorable sequences here is the unbelievably realistic looking car chase that happens 37 minutes into the film. The chase, which surely ranks among cinema’s most breath-taking, is staged with such verisimilitude – long before computers could make things look this real – that you’re inclined to gasp, wince and want to look away many times throughout the six-minute sequence. The only problem is that the chase is precipitated not by the good-guys dogging the bad-guys a la Bullitt or The French Connection but by a childishly petulant grudge held by a very un-smart thug, who seems to have plenty of time from his henchman duties to nurse his tortured little feelings and, oh, trash, the on-again/off-again rainy streets of Hamburg and nearly slaughter half its population. Still, while the chase often threatens to become ridiculous, it makes for some truly remarkable cinema.

The film was directed by Michele Lupo (1932-89), one of Italy’s many genre directors, in a rather flat style that can only be called workmanlike. He relies on the strong presence of his actors, the strong sense of location that Hamburg naturally provides and the particularly graceful way Tonino Delli Colli (1922-2005) photographs it all. Yes, it’s a hack job. But all of these plusses negate Lupo’s fairly pedestrian take on the proceedings.

The cinematography is probably what makes this film so singularly mesmerizing. Tonino Delli Colli (1922-2005), who shot many of the well-known films of Federico Fellini, Pier Paulo Pasolini and Sergio Leone, is particularly adept here where architecture is concerned. He leaves the actors to the director, which means the actors are pretty much on their own throughout. Delli Colli’s camera swoops around the insurance building (at times visually quoting Louis Malle's fateful caper film Ascenseur pour l'echafaud/Elevator to the Gallows), the pawn shop, the interior of Steve and Anna’s drab little house and Marco’s circus tent with a sure hand that constantly evokes some sort of chill, recalling the cool architectural finesse photographer Vittorio Storaro lent to the giallo Giornata near per l’ariete/The Fifth Cord (1971) (also effectively scored by Ennio Morricone) and the strong sense of architecture present in the recent film The International. Delli Colli, on the other hand, films these places in such a way that brings out their utter lack of personality and total lack of warmth or human feeling. The only place that has any love in it – the house that Anna and Steve share – Steve considers to be “a dump” and allows Marco to invade without any thought whatsoever to Anna.

Another one of the film’s superior advantages is Ennio Morricone’s sad, nearly fatalistic score. Appropriately located somewhere between the romantic and crime thriller styles his music was exhibiting to excess at the time, Morricone properly scores The Master Touch like a film noir, with a trumpet echoing through a long, dark night of the soul. One can almost feel the icy sting of a cold morning rain, just before sun-up and the miserable fate that probably befalls us all in Morricone’s plaintive trumpet wailing. In my estimation, Morricone’s main theme, “Un Uomo da Rispettare,” is among the ten or eleven best main themes he’s ever done for a film. To wit, it can be heard, in its full eleven and a half minute glory on the excellent 2005 Ipecac Morricone compilation titled Crime and Dissonance.

A soundtrack album to Un Uomo da Rispettare featuring nine tracks, totaling about 36 minutes of music, was issued in Italy in 1972 on CBS Records. It features the entrancing eleven and a half minute title track; the ballad titled “A Florinda” (the first of the two tracks with this title), the sadly romantic theme used for the argument/discussion scenes between Anna and Steve (perfect to hear how Morricone scores a breaking heart); “L’Incarico,” a brief but welcome jazz version of the main theme; and “18 Pari,” one of Morricone’s great breezy bossas (which I don’t recall hearing in the film). A CD using the same great cover graphics (shown above) and the same track line up was issued by Sugar Music in Japan in 1995. The album was also issued in 2002 in Italy on the Hexacord label and three tracks from the soundtrack (“Prima di Lasciarla,” “A Florinda” and “18 Pari”) appear on the 2005 Dagored compilation titled The Library Vol. 1: Ennio Morricone. Suffice it to say, all of these recordings may be hard to find now, but the title track appearing on Crime and Dissonance is currently available from iTunes.

A soundtrack album to Un Uomo da Rispettare featuring nine tracks, totaling about 36 minutes of music, was issued in Italy in 1972 on CBS Records. It features the entrancing eleven and a half minute title track; the ballad titled “A Florinda” (the first of the two tracks with this title), the sadly romantic theme used for the argument/discussion scenes between Anna and Steve (perfect to hear how Morricone scores a breaking heart); “L’Incarico,” a brief but welcome jazz version of the main theme; and “18 Pari,” one of Morricone’s great breezy bossas (which I don’t recall hearing in the film). A CD using the same great cover graphics (shown above) and the same track line up was issued by Sugar Music in Japan in 1995. The album was also issued in 2002 in Italy on the Hexacord label and three tracks from the soundtrack (“Prima di Lasciarla,” “A Florinda” and “18 Pari”) appear on the 2005 Dagored compilation titled The Library Vol. 1: Ennio Morricone. Suffice it to say, all of these recordings may be hard to find now, but the title track appearing on Crime and Dissonance is currently available from iTunes.It’s not a great film. It’s not even one of the better films attached to Kirk Douglas, Florinda Bolkan, Tonino Delli Colli or Ennio Morricone. But Un Uomo Da Rispettare/The Master Touch is worth savoring for the contribution, if not collaboration, of each of these cinematic masters.

About the DVD: Unfortunately, it seems The Master Touch has fallen into public-domain hell where free-market devils banking on Kirk Douglas’ name are legally able to produce endlessly awful versions of the film, which probably deserves much, much, MUCH better treatment.

There are many different versions of this film currently available on DVD and most of them are hardly worth the effort – even at five or ten bucks a pop. The copy I finally secured after much trial and tribulation is the Passion Productions version, issued in early 2002. The box art, pictured above, is simply awful and worse than some of the other versions out there. But the film on the region-free DVD is probably worth the purchase price.

The film, which claims to run for 112 minutes actually runs for 96 minutes (like most of the other versions, I think) and it is presented in a very watchable, near-widescreen format. It’s matted, not the 1:66:1 aspect ratio of a true widescreen production, as the opening credits clearly show. The print quality is also marginal at best. Not the best you’ll ever see.

Scratches, yes. Grain, whoa yes. But the light levels are decent – and nothing at all like some of the shoddier looking productions of other films that claim to be digitally enhanced. Consider some of the cobbled-together prints of “lost films” some of the majors put out on DVD and you won’t feel so put out by the seven bucks this one will cost you.

I’m not sure if a true 112-minute version of the DVD exists. I welcome anyone who can point me in the right direction of one. However, if anyone wants to know, I got mine from amazon.com. I’ve waited years for Criterion or some other major player to do this film justice. But it’s probably never going to happen. Never.

RIP Senator Ted Kennedy

My thoughts and prayers are with the loved ones but I hope Senator Kennedy rests in peace, in a good place. Senator Kennedy has served the interests of this country more than many of us could ever thank him for. I wish I would have tried. I had the great pleasure of seeing the great Senator on the Senate floor about 10 years ago and could not have been more impressed or amazed in the government of our nation. Senator Kennedy is like royalty. He stood for all the right causes for all the right reasons right up until the day he died. While I see the Kennedy legacy in President Obama, I truly, madly, deeply hope Senator Edward Moore "Ted" Kennedy's legacy lives on. Somehow. Some way. Peace be with you and thank you, Senator Kennedy. RIP.

My thoughts and prayers are with the loved ones but I hope Senator Kennedy rests in peace, in a good place. Senator Kennedy has served the interests of this country more than many of us could ever thank him for. I wish I would have tried. I had the great pleasure of seeing the great Senator on the Senate floor about 10 years ago and could not have been more impressed or amazed in the government of our nation. Senator Kennedy is like royalty. He stood for all the right causes for all the right reasons right up until the day he died. While I see the Kennedy legacy in President Obama, I truly, madly, deeply hope Senator Edward Moore "Ted" Kennedy's legacy lives on. Somehow. Some way. Peace be with you and thank you, Senator Kennedy. RIP.

Oliver Nelson “The Kennedy Dream”

At a time when most of what used to be called “record companies,” are slashing budgets, cutting staff or going out of business altogether, Universal Music has been doing a superb job reissuing their huge treasure trove of jazz on CD. Through its Originals program, dozens of nearly forgotten jazz gems from the old Verve, Impulse, A&M, Philips, MGM, Mercury and Limelight catalogs are finding their way back onto the nearly 30-year old CD format.

At a time when most of what used to be called “record companies,” are slashing budgets, cutting staff or going out of business altogether, Universal Music has been doing a superb job reissuing their huge treasure trove of jazz on CD. Through its Originals program, dozens of nearly forgotten jazz gems from the old Verve, Impulse, A&M, Philips, MGM, Mercury and Limelight catalogs are finding their way back onto the nearly 30-year old CD format. The other majors (WEA, Sony, EMI) are either (thankfully) licensing albums out to boutique reissue labels like Water, Wounded Bird, Collector’s Choice and Collectables or making the music available for download only. Universal Music’s Original series is catering its great wealth of music to what has become an appreciative, though small and shrinking, market base that still likes to have and hold music with great cover art, musical credits and, in some cases, liner notes (which CDs tend to make almost impossible to read).

To get an idea of just how obscure some of these Originals releases are, take the Oliver Nelson (1932-75) album The Kennedy Dream: A Musical Tribute To John Fitzgerald Kennedy, originally released in 1967 by the Impulse Records label. Even in 1967, hardly anyone knew the record existed. These days, Oliver Nelson’s name barely registers. Sadly, he does not get the recognition he so richly deserves outside of the required nod to “Stolen Moments,” Blues and the Abstract Truth, the brilliant 1961 album “Stolen Moments” appeared on, and – often snidely – a handful of Jimmy Smith’s Verve albums.

The release of Oliver Nelson’s The Kennedy Dream is, indeed, cause for celebration. It is a masterful work that ranks high among the composer’s very best work. This tribute is probably one of the most personal, deeply felt pieces he was ever asked to do outside of Afro/American Sketches (Prestige, 1961) or Black Brown and Beautiful (Flying Dutchman, 1969). And the sincerity of his conviction shines through, producing an impassioned tribute to an inspired leader who inspired much hope for a brighter future and a better world.

The Kennedy Dream is a semi-orchestral suite in which seven of the eight compositions are launched by brief, yet memorable sections of John Kennedy’s speeches about equality and positive change. The recording was made over two days in February 1967, with a small, uncredited cast of New York’s finest session men, including Snooky Young on trumpet, Jerome Richardson and Jerry Dodgion on reeds, Phil Woods on alto sax (and solos), Phil Bodner on English horn, Danny Bank on bass clarinet, Don Butterfield on tuba, Hank Jones on piano and harpsichord, George Duvivier on bass and Grady Tate on drums.

Despite the stirring of Kennedy’s words and the rush of the occasional solo, one’s attention and admiration is drawn throughout to Nelson’s beautiful melodies, constructed with evocative passages and very personable turns of phrase. His writing for strings, for which he never got his proper due, is remarkable; filled with a purposeful passion and a rare and poetic restraint.

Each of the suite’s eight pieces have a chapter-like quality in what could be considered a musical novella – not quite the magnum opus it might have been under different circumstances (thanks to producer Bob Thiele, Nelson was probably lucky to get this record made at all) but certainly more reflective and insightful than a mere song could have ever conveyed. Still, the album’s highlights include “Let The Word Go Forth” (based on Example 45 from Nelson’s instruction book Patterns For Saxophone), “The Artist’s Rightful Place,” known elsewhere as “Patterns For Orchestra” and, most notably, the outstanding “The Rights of All,” featuring a pizzicato strings rhythm and a gripping Phil Woods solo.

Released on CD* in what would have been Kennedy’s 82nd year – and during the first year into the term of a president who presents as much hope for positive change as Kennedy once did - The Kennedy Dream is a remarkable work from a period when orchestral jazz was not all that uncommon. It is as much a musical tribute to the presidential legacy of John Fitzgerald Kennedy as it is a documented tribute to the beautiful musical legacy of Oliver Edward Nelson.

* The Kennedy Dream was included on the 6-CD Mosaic boxset, Oliver Nelson: The Argo, Verve and Impulse Big Band Studio Sessions issued in February 2006.

Saturday, August 22, 2009

Jimmy Smith “Testifyin’”

Organ great Jimmy Smith (1925-2005) spent a large part of his career recording large-group, ostensibly commercial, efforts for the MGM family of labels, from 1962’s noteworthy Bashin’ (on Verve, with Oliver Nelson) to 1973’s ultra-grooving and totally worthwhile Black Smith (on Pride).

Organ great Jimmy Smith (1925-2005) spent a large part of his career recording large-group, ostensibly commercial, efforts for the MGM family of labels, from 1962’s noteworthy Bashin’ (on Verve, with Oliver Nelson) to 1973’s ultra-grooving and totally worthwhile Black Smith (on Pride). Despite several small-group classics made during those years (Organ Grinder Swing, The Boss and, of course, Root Down), it had been nearly a lifetime since the small-group Blue Note classics like The Sermon, Midnight Special and Back at the Chicken Shack that not only made Smith a jazz star but actually made the Hammond B-3 an important sound for jazz.

By 1974, not only was the face of jazz changing distinctly from whatever it was before, but the Hammond B-3 was distinctively falling out of favor among jazz listeners. It was no longer cool to play this 500-pound elephant when a variety of new, comparatively lightweight (and easier to travel) electronic keyboard sounds – from the RMI Rocksichord and Moog Synthesizer to the Farifisa organ and the Fender Rhodes – made the Hammond B-3 organ sound like your grandfather’s kind of music. Many jazz organ players made the switch to the electronic keyboards. Or they just stopped playing altogether and faded away into obscurity.

Like many jazzers of his generation, Jimmy Smith had relocated in the early 1970s from New York City to Los Angeles – where more musical opportunity seemed to present itself. While others went into the session cesspool, Jimmy Smith stuck to the organ and even opened his own supper club, where he’d often feature himself fronting a small group, doing what he did best – better than anyone else, too, even by his own admission – playing the hell out of the Hammond B-3 organ. He continued drawing audiences to marvel at his thing. But even though he must have thought he was a relic from days gone by, no one could deny he wasn’t still “the boss,” the absolute boss, of the B-3.

With the market shifts and lack of label interest in organ music, Jimmy Smith and his wife/manager, Lola, launched their own label, Mojo, and released a whopping two albums during 1974-75, truly the darkest days of Hammond jazz. The first of these albums, Paid In Full, is a 1974 studio session with the great Ray Crawford on guitar, Larry Gales on bass, Donald Dean on drums and Buck Clarke on percussion. The second album, Jimmy Smith ‘75 (mimicking a number of Westbound jazz album titles of the same year) combined a live October 1974 trio performance featuring Crawford and Dean in Tel Aviv, Israel, of all places, with a rocking 1974 session that added several percussionists to the group.

Both of these albums have finally been combined to produce a CD titled Testifyin', a terrific example of the little-known period of Jimmy Smith's music that deserves to be much better known.

The four long tracks that comprise Paid In Full make this CD worth every cent. Both Crawford and Dean were along for the ride on Smith’s remarkable 1972 album Bluesmith - but here the vibe is distinctly different. Perhaps it’s the fact that Bluesmith bassist, the great Leroy Vinnegar, is swapped out here for the somewhat more contemporary Larry Gales (1936-95). Gales, already a veteran of the Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, Sonny Stitt and, most notably, Thelonius Monk bands, adds something a little different to Smith’s groove, something that really spurs Smith and company on to make their electrified sounds sound more electrifying in a more electrified age.

But what is even more substantial here is the prominence Smith gives to guitarist Ray Crawford (1924-97) – who shines particularly on “Killing Me Softly With His Song,” something that seems conceived especially for him – which is good considering the lack of solo opportunities Ray Crawford ever got during his career. Crawford steps forward magnificently here to become Smith’s partner in crime. He’s even adapted his guitar style from the classic sound he so beautifully lent to Gil Evans’ “La Nevada” to come up with something a little more hip for the times. This is especially notable in the album’s best tracks: the awesome blues of “Bro Pugh” (named for Lonzo Pugh of Phoenix, Arizona – listen to the way Smith mans the changes, first, on organ, and then, more spectacularly, on piano) and the break-beat classic “Can’t Get Enough” (first heard on CD on the excellent Luv ‘N’ Haight compilation, Can’t Get Enough issued in 1995). Smith is glorious throughout Paid in Full’s four tracks, proving he was still the boss and that organ jazz still mattered.

The Jimmy Smith ‘75 album is a mixed bag which becomes evident as the funky “Can’t Get Enough” fades into the apparent audience favorite “Organ Grinder’s (sic) Swing,” a brief respite into the deep, dark past of the Hammond’s glory days. It’s a decent enough performance, followed by live takes of Cole Porter’s “It’s Alright With Me” (where Smith sounds more like Jimmy McGriff than himself), Kris Kristofferson’s “For The Good Times” (a feature for Ray Crawford), the noodle-y “Jazz Scattin’” and the seemingly requisite “Got My Mojo Workin,” a Muddy Waters hit that Smith re-popularized in the mid-1960s and became the basis for his label’s name. Here, it is justified by a particularly dazzling (yet brief) solo Smith takes to say this sort of thing still mattered. He makes a pretty damned convincing case.

Even so, things pick up with a particularly electrifying studio piece called “Testifyin’,” which, of course, is the title of this CD. Crawford rocks here in his phase-shifted way and Smith, of course, preaches the gospel like no one ever could. It comes through again on “Lookin’ Ain’t Getting’” and on a surprisingly funky take on Sonny Rollins’ “St. Thomas” (which must have sounded odd to anyone digging this or any other jazz record in 1975). The pop covers actually sound a little out of place here and include the unknown Daryle Chinn’s “More To Life (Than Living)” – which is probably better suited to excellent and worthwhile Black Smith - and the weird cover of the Roberta Flack hit “Feel Like Making Love,” with Crawford’s gorgeous guitarisms nearly being drowned by some of Jimmy Smith’s strange and unnecessary growling protestations (“That’s the TIME…”).

Both albums are included in their entirety for the first time ever on this CD, given the not altogether inappropriate title, Testifyin’ (one of the better songs on the second of the two albums). Issued by the Spanish label, Groove Hut, it’s a great collection, focusing on a very little-known and still interesting period of Jimmy Smith’s music and a fairly necessary chapter of the man’s music.

The sound here is more than adequate, despite the probability that it was copped from well-cleaned vinyl rips. And the cover art and typography leave more than something to be desired. Nowhere to be seen is the original cover art of Paid in Full or the trippy gatefold sleeve of Jimmy Smith ‘75. On the other hand, John Blackman’s liner notes are well written and help set the music in its proper context.

Jimmy Smith would hereafter go on to record three albums for the Mercury label, each of which is worthy in its own right – particularly 1977’s oddly commercial yet addictive Sit On It! - then reunite with Lalo Schifrin in 1980 for the excellent The Cat Strikes Again. I’ll try to get around to covering these on this blog someday. It makes for some great music…still!

But all of this is to say that, despite attention being drawn elsewhere at the time, organ great Jimmy Smith was still making legendary music worth hearing and savoring during the 1970s. Testifyin’ is ample proof.

For more information, check out the Groove Hut site, here.

Tuesday, August 18, 2009

Disco Jazz

Disco lives! At least here, that is.

Disco lives! At least here, that is. A great idea that, surprisingly, has yet to be picked up, acknowledged or exploited elsewhere, Disco Jazz combines 60s-era lounge instrumentalists with 70s-era disco instrumentalists, covering a variety of disco-oriented instrumentals that have a strong feel of jazz about them. Much of this music has never seen the light of day on CD and it’s a real pleasure to hear it collected and compiled so darned well.

Disco Jazz is part of Universal’s budget-priced Jazz Club series, which makes sense because not only was much of the music that fits this description made for Universal-owned labels like Polydor, ABC, Motown, 20th Century and Casablanca Records back in the day, but the best moments that could be considered “disco jazz” all appeared on Universal labels. Much of it is heard right here.

This collection, tastefully compiled by iconoclastic and retro-visionary producer Matthias Künnecke, gathers 17 highlights of the “disco jazz” era, all of it recorded during disco’s high years, between 1975 and 1980. Some rare and highly collectable gems – of predominantly German descent – are to be found here, including a European 45 only cover of Herb Alpert’s “Rise” by James Last (recorded in 1979 in the US), “On The Road to Philadelphia” and “Salsoul Motion” by Kai Warner (James Last’s brother) and an exhilarating cover of Chuck Mangione’s excellent “Land of Make Believe,” recorded by Peter Thomas from a little-known disco album he cut in 1977.

I had the pleasure of suggesting a number of the disco nuggets that are included here, such as Rhythm Heritage’s riveting take on Duke Ellington’s “Caravan” (from the same album that yielded the group’s 1975 hit “Theme From S.W.A.T.”), James Last’s “Falling Star” (from one of his few American albums, 1980’s Seduction), Brass Fever’s bracing take on Gershwin’s “Summertime” (from the studio group’s second and final album, 1977’s Time Is Running Out), Patrick Williams’ “Come On And Shine” (1977) and Paul Mauriat’s disco redux of his worldwide hit “Love Is (Still) Blue” (1976). I also proposed Werner Baumgart’s invigorating “Long Island Sound” (1980) and Bert Kaempfert’s own take on Saturday Night Fever, “Keep on Dancing” (1979, from his last studio album, Smile). Unfortunately, my suggestion to include Meco’s ultra-funky take on the Classics IV’s “Spooky” from his 1979 Casablanca album Moondancer didn’t make the cut, so the producer replaced it with the album’s far more conventional title cut.

Elsewhere here is Love Unlimited Orchestra’s “Brazilian Love Song,” Rhythm Heritage’s “Dance The Night Away” and “Sky’s The Limit” (both written by Victor Feldman), Peter Thomas' version of "House of the Rising Sun" and Meco’s “Meco’s Theme,” rounding out what is a perfectly enjoyable and well-programmed set of revisionist jazz just waiting for justifiable reconsideration. Great cover, too.

Darren Heinrich Trio “New Vintage Tunes for the Hammond Organ”

Sydney-based organist Darren Heinrich resurrects a tradition that may not have existed since sometime during the late 1960s, some 40 years ago. It’s not the organ trio he helms with aplomb here, which was ushered into revival by the acid jazz scene of the mid 1980s. It’s the feeling for organ jazz that Heinrich has re-discovered and imparts on his perfectly dubbed New Vintage Tunes for the Hammond Organ.

Sydney-based organist Darren Heinrich resurrects a tradition that may not have existed since sometime during the late 1960s, some 40 years ago. It’s not the organ trio he helms with aplomb here, which was ushered into revival by the acid jazz scene of the mid 1980s. It’s the feeling for organ jazz that Heinrich has re-discovered and imparts on his perfectly dubbed New Vintage Tunes for the Hammond Organ.Back when stores were littered with the records of Jimmy Smith, Jimmy McGriff, Jack McDuff, Larry Young, Charles Earland, Groove Holmes, John Patton, Shirley Scott, Lonnie Smith, Don Patterson and Johnny “Hammond” Smith – to name just a few – it was easy to find music like this. But after electric keyboards made the Hammond B-3 a useless relic of a bygone era, neither the revivalists nor the old masters plugging in their dusty old B-3s were able to quite bring back the feeling that was there in the first place. Joey DeFranscesco came close. But after two decades of recording, even he has yet to wax a must-have record.

New Vintage Tunes for the Hammond Organ is a mouthful that may get it exactly right. This music is sincerely delivered and strikingly unaffected, something this listener hasn’t heard on an organ jazz record for a very long time. It never struggles to be something it is not nor re-creates something that already exists. If I want to hear Jimmy Smith, I’ll buy a Jimmy Smith CD, thank you. There are ten originals here that are so strong on their own that no fake-book standard is required or needed. No special guests that are there only to ensure an emotional connection are necessary. No gimmicks that call to mind something or someone else are invited in.

As a player and as a thinker, Darren Heinrich most recalls mid-1960s-era Larry Young and, to a much lesser extent, Blue Note-era Lonnie Smith (Heinrich is actually studying with the good Doctor this summer). But this is not to say that Heinrich hi-jacks or imitates these organ masters. It’s the feeling these organists brought to their recordings that Heinrich captures so well. It’s the vibe and vibrancy the music had back then. Heinrich has something to say that's worth tuning into and, like the organ grinders of yore, it sticks with you

Heinrich works with two trios here. One, featuring notable Sydney-based guitarist Steve Brien and drummer Andrew Dickeson, both of whom accompany Heinrich on his recent The Jimmy Smith/Larry Young Project LIVE, works in the mid-1960s mode that recalls the melodically constructed yet introspective musings of Larry Young circa 1964-65, when the organist was working a lot with Grant Green.

This trio, which mans exactly half of the disc’s songs, provides what for me are the disc’s true highlights, from the mid-tempo blues of “Lunar,” the brainy funk of “Willow” and the stand-out groove of the catchy, butt-shaking, finger-snapping “The Poledancer” to the “Autumn in New York” styled ballad “I Don’t Know” and “Early Autumn,” which could have been the second track on any Blue Note album of the mid 1960s. The hit-worthy “Poledancer” is the album’s best moment and precisely the type of insistent groove you’d hear blasting out of any number of juke boxes back in the day. It’ll certainly turn heads to wonder who is doing it if it happens to be in Pandora Radio’s playlist.

The other grouping, featuring guitarist Simon Reif and drummer Tim Firth, is quite a bit greasier than the first, wallowing in the mid-1960s fatback of Jack McDuff by way of Lonnie Smith (both, coincidentally, played a lot with George Benson at the time). It’s Reif and Firth who give the group the Jack McDuff vibe. Heinrich brings to it that exquisitely soulful touch Lonnie Smith brought to his early Blue Note albums. While it’s an excellent contrast to the other more cerebral grouping, this trio doesn’t escape Heinrich’s consistent oversight. He makes gravy out of “Hicksville,” “Meanderthal” and the album’s second-best groover, “Slinky” (titled for the toy the song reminds Heinrich of, hence the photo on the disc’s cover – which nearly makes this the CD’s title tune). The trio ruminates rather engagingly on the atmospheric “Hello Goodbye,” on which Heinrich recalls some of Shirley Scott’s quieter moments, and the playfully serious “Three Shades of Green” – which, if it is meant to honor guitarist Grant Green, gets a marvelous tribute from guitarist Reif and Heirich, the excellent synthesist of John Patton and Larry Young, as the third shade.

The CD includes alternate takes of both “Meanderthal” and “Willow” which switches trios from the earlier versions, making a fascinating case for the different vibe each group brings to Heinrich’s approach. What you hear is everybody listening to everyone else, the way jazz was meant to be.

A pure delight throughout, New Vintage Tunes for the Hammond Organ is an ideal celebration of the Hammond organ on its 75th birthday and should work to place Darren Heinrich in the pantheon of great jazz organists. For more information, visit Darren Heinrich’s dazzjazz site.

Monday, August 17, 2009

P-Funk n’jazz

Say what you will about the P-Funk mob, and many people have, but those guys could play…and play and play and play. Despite whatever substances were aiding them along the way – and there many – there was plenty of raw talent, free-thinking and freedom-seeking attitude that fuelled this band’s musical invention and gave birth to one of the 20th century’s greatest musical concoctions.

Say what you will about the P-Funk mob, and many people have, but those guys could play…and play and play and play. Despite whatever substances were aiding them along the way – and there many – there was plenty of raw talent, free-thinking and freedom-seeking attitude that fuelled this band’s musical invention and gave birth to one of the 20th century’s greatest musical concoctions. Known under many guises, but most famously as Parliament, Funkadelic and Bootsy’s Rubber Band, the P-Funk cosmology was innovative in any number of ways, pioneering a new form of music that obviously mixed rock with R&B but was predicated upon a jazz-like innovation that borders on classical music.

Get behind all the often inane lyrics, even those that purported to have a serious message, cartoon chants and the helplessly addictive grooves, and you have some serious musical talent here, worthy of note on its own merit. This wasn’t merely funk. It was something deeper, altogether more serious than simple funk. It was THE funk.

The P-Funkseters were inventing a new musical language, peopling a whole new universe that no one had ever heard before. Overseen by George Clinton, equal parts P.T. Barnum and Teo Macero, the P-Funk crew was a sprawling, ever-changing amalgam of many, many individual talents, the most notable of whom were probably Eddie Hazel, Bernie Worrell and Bootsy Collins. (Please forgive me if I left anyone out – there was a plethora of talent to be heard here, nearly all of it significant – but the folks I named here strike me as much as architects of the P-Funk sound as contributors to it.)

After years of toiling in the otherwise hugely popular Detroit music scene during the late 50s and early 60s, mostly under the guise of The Parliaments, George Clinton discovered something truly unique when he let the musicians step forward into the spotlight to form Funkadelic, perhaps the world’s very first jam band. Funkadelic actually landed a recording contract with Detroit’s Westbound Records in 1969, and the group went on to shape a whole new sound for themselves and break a lot of musical barriers over the course of eight wildly divergent records through 1976, most memorably on 1971’s Maggot Brain. Clinton called it all “A Parliafunkdelicment Thang,” which is where the shorthanded P-Funk name came from, and it grew from there.

Clinton revived Parliament in 1974 as a much more soulful, somewhat more radio-friendly version of Funkadelic, bringing the vocalists back up front and replacing the guitar domination with layered keyboards and horny horns. It hit in 1975 when “Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker)” crossed over and became a huge radio sensation. Clinton started spreading his wings and expanding the organization (and label dealings) to feature multi-instrumentalist and former J.B., William “Bootsy” Collins, the back-up vocalists (Brides of Funkenstein, Parlet), the horn section, led by former J.B. Fred Wesley and featuring another former J.B., Maceo Parker, among many, many others including the group’s prominent instrumentalists, Eddie Hazel and Bernie Worrell.

There was so much music coming out of the P-Funk fold between 1977 and 1980 that some of it was either negligible or just slipped between the grooves of all the other stuff that lined the shelves. My intention here is not to cover the entirety of the voluminous P-Funk catalog nor review all the highlights that should be heard, savored or appreciated. Plenty has already been written about these guys and their music (check out The Motherpage for an excellent resource of all-things P-Funk) and chances are you already know what you like or what you want out of P-Funk.

The focus here is on some of the lesser-known music that either spotlights or should spotlight the P-Funk instrumentalists. Funkadelic is probably the best place to hear P-Funk’s most overt musicianship. Mostly a vehicle for guitarists Eddie Hazel and, later, Mike Hampton, Funkadelic was also a particularly creative canvas for keyboardist Bernie Worrell. It’s most apparent in the instrumentals, from Hazel’s magnum opus “Maggot Brain” (1971) to other (mostly) instrumentals including “You Hit The Nail On The Head” and “A Joyful Process” from 1972’s America Eats Its Young, “Nappy Dugout” from 1973’s Cosmic Slop, “Atmospheres” (a feature for Bernie Worrell) from 1975’s Let’s Take It To The Stage, “Tales of Kidd Funkadelic” from the 1976 album, “Hardcore Jollies” (featuring Hampton) from another 1976 album, “Lunchmeataphobia,” “P.E. Squad/Doodoo Chasers” and “Maggot Brain” from the hit One Nation Under A Groove, “Field Maneuvers” from 1979’s Uncle Jam Wants You) and superfluously on “Brettino’s Bounce” from 1981’s Electric Spanking of War Babies. It’s usually what’s going on behind – almost beyond – the vocals heard that makes Funkadelic most interesting and, ultimately, timelessly enduring.

The focus here is on some of the lesser-known music that either spotlights or should spotlight the P-Funk instrumentalists. Funkadelic is probably the best place to hear P-Funk’s most overt musicianship. Mostly a vehicle for guitarists Eddie Hazel and, later, Mike Hampton, Funkadelic was also a particularly creative canvas for keyboardist Bernie Worrell. It’s most apparent in the instrumentals, from Hazel’s magnum opus “Maggot Brain” (1971) to other (mostly) instrumentals including “You Hit The Nail On The Head” and “A Joyful Process” from 1972’s America Eats Its Young, “Nappy Dugout” from 1973’s Cosmic Slop, “Atmospheres” (a feature for Bernie Worrell) from 1975’s Let’s Take It To The Stage, “Tales of Kidd Funkadelic” from the 1976 album, “Hardcore Jollies” (featuring Hampton) from another 1976 album, “Lunchmeataphobia,” “P.E. Squad/Doodoo Chasers” and “Maggot Brain” from the hit One Nation Under A Groove, “Field Maneuvers” from 1979’s Uncle Jam Wants You) and superfluously on “Brettino’s Bounce” from 1981’s Electric Spanking of War Babies. It’s usually what’s going on behind – almost beyond – the vocals heard that makes Funkadelic most interesting and, ultimately, timelessly enduring. Such was especially true of Parliament, which rose above the clouds with 1974’s Up For The Down Stroke. This version of the Funk Mob had been configured to be much more commercial, so the vocals get moved to the front and horns, which gave other groups like Kool & The Gang, the Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire, their sonic signature, were added. Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell co-wrote many of the group’s songs and are prominently featured on a variety of instruments throughout the grooves but only “Night of the Thumpasorus Peoples” (featuring Bootsy and Bernie) from 1975’s Mothership Connection) and the disco-y “The Big Bang Theory” from 1979’s Gloryhallastoopid (Pin The Tail On The Funky) reveal the instrumental side of Parliament – though “Flash Light” remains a monster of instrumental magic that should be savored and could be studied for creative technological prowess for years to come.

Such was especially true of Parliament, which rose above the clouds with 1974’s Up For The Down Stroke. This version of the Funk Mob had been configured to be much more commercial, so the vocals get moved to the front and horns, which gave other groups like Kool & The Gang, the Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire, their sonic signature, were added. Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell co-wrote many of the group’s songs and are prominently featured on a variety of instruments throughout the grooves but only “Night of the Thumpasorus Peoples” (featuring Bootsy and Bernie) from 1975’s Mothership Connection) and the disco-y “The Big Bang Theory” from 1979’s Gloryhallastoopid (Pin The Tail On The Funky) reveal the instrumental side of Parliament – though “Flash Light” remains a monster of instrumental magic that should be savored and could be studied for creative technological prowess for years to come. The following represents specific albums that should figure in any collection of P-Funk where the instrumentalists and their contributions mattered. While none are entirely satisfactory as self-contained musical statements (there’s certainly no funked-up Kind of Blue, Electric Ladyland or even “Flash Light” in the bunch), each deserves kudos for spotlighting specific instrumentalists well-deserving of a much better testament to their musical powers than what was captured on any one record that’s been released – or at least covered below.

A Blow For Me, A Toot For You - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1977): By the time Fred Wesley helmed his own P-Funk date in 1977, he’d already racked up time as part of James Brown’s band and as leader of its more instrumental offshoot, the renowned J.B.’s (their last album was 1975’s Hustle With Speed). He’d also contributed to such CTI albums as Hank Crawford’s I Hear A Symphony, Hank Crawford’s Back and Cajun Sunrise, Idris Muhammad’s House Of The Rising Sun, George Benson’s Good King Bad, Esther Phillips’ For All We Know and David Matthews’ Shoogie Wanna Boogie - all arranged by fellow J.B. alum, David Matthews. So this guy had his jazz/funk chops well in line. By the time of this album, Fred Wesley and fellow J.B. and Horny Horn partner Maceo Parker had been a significant part of the Parliament/Funkadelic fold for nearly two years, starting with the hugely popular Mothership Connection album and the hit “Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker).” Fred, Maceo & Co. start their own newly dubbed “Horny Horns” project off here with a long, excellent cover of Parliament’s 1974 “Up For The Down Stroke,” replacing the original’s vocals with vocals by the Brides of Funkenstein, a great string arrangement and some incredibly subtle, yet bracing, acoustic piano work from Bernie Worrell (Maceo is heard jamming at the very end, as the disco-y song fades out). Next, “A Blow For Me..” is a satisfactory meeting of the minds between Bootsy Collins and Fred Wesley, with Bootsy providing the heavy bass line and both Fred and Maceo free-styling (in tandem with Bernie Worrell) on electronically-fitted instruments (great trumpet lines aid de camp). “When In Doubt: Vamp,” a Clinton-Gary Schider-Bernie Worrell “piece,” was pretty much how George Clinton operated his musical operation – especially live. But here, the title is attached to a well-heeled jazz romp that launches into a beatific and utterly catchy (Rick Gardner) trumpet-fuelled New Orleans groove. “Four Play” is as close as the group comes to sounding like James Brown here (you got to wonder who’s doing the guitar that places this piece so firmly in rival Brown’s camp - Bootsy or Catfish…both veterans of James Brown, just like Maceo and Fred). But, oh, what a sound. Fred solos magnificently here. With its “Casper The Friendly/Funky Ghost” theme, “Between Two Sheets” suggests an outtake from an early Rubber Band album (the Casper character figured largely in the first Bootsy album, Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band). But, aside from a number of P-Funk namedropping that happens throughout the tune, both Fred and Maceo get nice funky features here. The one surprise on this album – which, fortunately, has seen the light of day on CD – is Fred Wesley’s moody, beautiful and most un-funky “Peace Fugue.” Sounding like a film theme, something like Lalo Schifrin’s “Street Tattoo” (from Boulevard Nights) crossed with Bill Conti’s Uncle Joe Shannon (both 1978), “Peace Fugue” actually stands out. Maybe it’s not as funky something you’d expect on an album like this, but it’s the album’s single most engaging moment. This might just well be one of the best P-Funk albums ever.

A Blow For Me, A Toot For You - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1977): By the time Fred Wesley helmed his own P-Funk date in 1977, he’d already racked up time as part of James Brown’s band and as leader of its more instrumental offshoot, the renowned J.B.’s (their last album was 1975’s Hustle With Speed). He’d also contributed to such CTI albums as Hank Crawford’s I Hear A Symphony, Hank Crawford’s Back and Cajun Sunrise, Idris Muhammad’s House Of The Rising Sun, George Benson’s Good King Bad, Esther Phillips’ For All We Know and David Matthews’ Shoogie Wanna Boogie - all arranged by fellow J.B. alum, David Matthews. So this guy had his jazz/funk chops well in line. By the time of this album, Fred Wesley and fellow J.B. and Horny Horn partner Maceo Parker had been a significant part of the Parliament/Funkadelic fold for nearly two years, starting with the hugely popular Mothership Connection album and the hit “Give Up The Funk (Tear The Roof Off The Sucker).” Fred, Maceo & Co. start their own newly dubbed “Horny Horns” project off here with a long, excellent cover of Parliament’s 1974 “Up For The Down Stroke,” replacing the original’s vocals with vocals by the Brides of Funkenstein, a great string arrangement and some incredibly subtle, yet bracing, acoustic piano work from Bernie Worrell (Maceo is heard jamming at the very end, as the disco-y song fades out). Next, “A Blow For Me..” is a satisfactory meeting of the minds between Bootsy Collins and Fred Wesley, with Bootsy providing the heavy bass line and both Fred and Maceo free-styling (in tandem with Bernie Worrell) on electronically-fitted instruments (great trumpet lines aid de camp). “When In Doubt: Vamp,” a Clinton-Gary Schider-Bernie Worrell “piece,” was pretty much how George Clinton operated his musical operation – especially live. But here, the title is attached to a well-heeled jazz romp that launches into a beatific and utterly catchy (Rick Gardner) trumpet-fuelled New Orleans groove. “Four Play” is as close as the group comes to sounding like James Brown here (you got to wonder who’s doing the guitar that places this piece so firmly in rival Brown’s camp - Bootsy or Catfish…both veterans of James Brown, just like Maceo and Fred). But, oh, what a sound. Fred solos magnificently here. With its “Casper The Friendly/Funky Ghost” theme, “Between Two Sheets” suggests an outtake from an early Rubber Band album (the Casper character figured largely in the first Bootsy album, Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band). But, aside from a number of P-Funk namedropping that happens throughout the tune, both Fred and Maceo get nice funky features here. The one surprise on this album – which, fortunately, has seen the light of day on CD – is Fred Wesley’s moody, beautiful and most un-funky “Peace Fugue.” Sounding like a film theme, something like Lalo Schifrin’s “Street Tattoo” (from Boulevard Nights) crossed with Bill Conti’s Uncle Joe Shannon (both 1978), “Peace Fugue” actually stands out. Maybe it’s not as funky something you’d expect on an album like this, but it’s the album’s single most engaging moment. This might just well be one of the best P-Funk albums ever.  Games Dames And Guitar Thangs - Eddie Hazel (Warner Bros., 1978): At the time of its release, guitarist Eddie Hazel’s debut – and sole – solo album was disappointing because of its odd choice of material and its very un-Parliament sound. It was probably nearly two decades later when I discovered the early Funkadelic records co-strategized by the unpredictable Hazel that I found this album further disappointing because that Hendrix edge Hazel had fostered – and nearly made his own - in the early 70s seemed now to lack focus, direction or even purpose in the disco age. And why the “California Dreamin’” cover? (This was also the 45-inch single Warner Bros. attempted to launch Hazel’s solo career with too. OK – yes, many acts at the time were getting weirdly famous redoing old hits from the 50s and 60s…but it was hard to believe that a flower-power hit could score in the age of Saturday Night Fever or even Grease.) As another decade or so has passed, I have finally warmed up to this rather hit-or-miss affair. At the time, personal problems prevented Hazel from devoting full attention to P-Funk, which – as a helmsman of Funkadelic – he left in 1971 and returned, sporadically, to in 1974 (Hazel isn’t heard on any of the Parliament or Funkadelic radio hits made around this time). But he and George Clinton assembled much of the P-Funk mob, including Bootsy Collins, Mike Hampton, the Brides of Funkenstein on background vocals on a few tracks and, notably, Bernie Worrell, and created a genuinely interesting document that attests fairly decently to the incredible talents of guitar god Eddie Hazel. It’s still a hard album to figure. There is good musicianship throughout. But any expectation that was there was to be confounded. By 1978, when this album was issued – with little or no fanfare whatsoever – who wanted to hear a black rock guitarist trying to do outmoded pop or try to get into the funked-up cartoons P-Funk was making millions off of? Even Eddie Hazel seems to have trouble figuring out how to fit into any concept that would have worked in 1978. Still, he succeeds in wrenching meaning out of this barely successful jazz-rock experiment. Hazel, in all his glory, is heard absolutely in his element in “So Goes The Story.” But the first notable piece is the surprising cover of The Beatles’ “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” which predates the Robert Stigwood-produced Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band extravaganza by a few weeks. Why wasn’t Hazel asked to contribute to this film? Hazel is astronomical here: everything you want and expect from the guitarist – a genius, set alight by an incendiary Beatles tune. Doesn’t seem like something Funkadelic would touch (though there was an odd cover of “She Loves You” on 1981’s The Electric Spanking of War Babies). But Hazel – again – nearly makes it his own. “Physical Love” is the same tune heard on Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band (Warner Bros., 1976) with Hazel’s guitar replacing the vocalists on Bootsy’s version. Hazel gives this song the heated passion Bootsy’s near-goofy version somehow lacks (although Garry Shider’s guitar and Bernie Worrell’s synth solo give this piece some of the greatness it probably deserves). Perhaps it’s the pain of desire. It sings out. The album’s stand-out track is the all-too brief bit of electro funk called “What About It?,” credited to both Eddie Hazel and George Clinton. It’s a brilliant instrumental that shows Hazel’s penchant for riveting guitarisms and a funky edge (remember The Temp’s great “Shakey Ground”?). It also boasts some of the great guitartastics Mike Hampton brought to the P-fold. It would have been fascinating if Hazel (or Clinton) let the whole album drive down this path. Still, it’s a great listen, if never wholly satisfying. Hazel continued recording with the P-Funk mob on and off until his death in December 1992. An EP with Hazel-oriented outtakes titled Jams From The Heart was issued in 1994 and folded, with different titles, into another release called Rest In P. But to hear one of the great Eddie Hazel P-Funk concoctions from this period (while he was Bonnie Pointer’s musical director), check out “I’m Holding You Responsible” from The Brides of Funkenstein’s Never Buy Texas From A Cowboy (Atlantic, 1979).

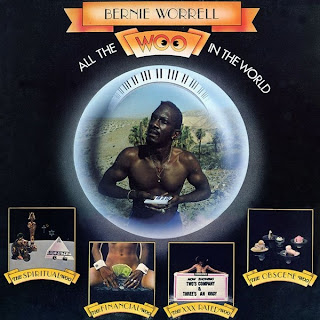

Games Dames And Guitar Thangs - Eddie Hazel (Warner Bros., 1978): At the time of its release, guitarist Eddie Hazel’s debut – and sole – solo album was disappointing because of its odd choice of material and its very un-Parliament sound. It was probably nearly two decades later when I discovered the early Funkadelic records co-strategized by the unpredictable Hazel that I found this album further disappointing because that Hendrix edge Hazel had fostered – and nearly made his own - in the early 70s seemed now to lack focus, direction or even purpose in the disco age. And why the “California Dreamin’” cover? (This was also the 45-inch single Warner Bros. attempted to launch Hazel’s solo career with too. OK – yes, many acts at the time were getting weirdly famous redoing old hits from the 50s and 60s…but it was hard to believe that a flower-power hit could score in the age of Saturday Night Fever or even Grease.) As another decade or so has passed, I have finally warmed up to this rather hit-or-miss affair. At the time, personal problems prevented Hazel from devoting full attention to P-Funk, which – as a helmsman of Funkadelic – he left in 1971 and returned, sporadically, to in 1974 (Hazel isn’t heard on any of the Parliament or Funkadelic radio hits made around this time). But he and George Clinton assembled much of the P-Funk mob, including Bootsy Collins, Mike Hampton, the Brides of Funkenstein on background vocals on a few tracks and, notably, Bernie Worrell, and created a genuinely interesting document that attests fairly decently to the incredible talents of guitar god Eddie Hazel. It’s still a hard album to figure. There is good musicianship throughout. But any expectation that was there was to be confounded. By 1978, when this album was issued – with little or no fanfare whatsoever – who wanted to hear a black rock guitarist trying to do outmoded pop or try to get into the funked-up cartoons P-Funk was making millions off of? Even Eddie Hazel seems to have trouble figuring out how to fit into any concept that would have worked in 1978. Still, he succeeds in wrenching meaning out of this barely successful jazz-rock experiment. Hazel, in all his glory, is heard absolutely in his element in “So Goes The Story.” But the first notable piece is the surprising cover of The Beatles’ “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” which predates the Robert Stigwood-produced Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band extravaganza by a few weeks. Why wasn’t Hazel asked to contribute to this film? Hazel is astronomical here: everything you want and expect from the guitarist – a genius, set alight by an incendiary Beatles tune. Doesn’t seem like something Funkadelic would touch (though there was an odd cover of “She Loves You” on 1981’s The Electric Spanking of War Babies). But Hazel – again – nearly makes it his own. “Physical Love” is the same tune heard on Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band (Warner Bros., 1976) with Hazel’s guitar replacing the vocalists on Bootsy’s version. Hazel gives this song the heated passion Bootsy’s near-goofy version somehow lacks (although Garry Shider’s guitar and Bernie Worrell’s synth solo give this piece some of the greatness it probably deserves). Perhaps it’s the pain of desire. It sings out. The album’s stand-out track is the all-too brief bit of electro funk called “What About It?,” credited to both Eddie Hazel and George Clinton. It’s a brilliant instrumental that shows Hazel’s penchant for riveting guitarisms and a funky edge (remember The Temp’s great “Shakey Ground”?). It also boasts some of the great guitartastics Mike Hampton brought to the P-fold. It would have been fascinating if Hazel (or Clinton) let the whole album drive down this path. Still, it’s a great listen, if never wholly satisfying. Hazel continued recording with the P-Funk mob on and off until his death in December 1992. An EP with Hazel-oriented outtakes titled Jams From The Heart was issued in 1994 and folded, with different titles, into another release called Rest In P. But to hear one of the great Eddie Hazel P-Funk concoctions from this period (while he was Bonnie Pointer’s musical director), check out “I’m Holding You Responsible” from The Brides of Funkenstein’s Never Buy Texas From A Cowboy (Atlantic, 1979). All The Woo In The World - Bernie Worrell (Arista, 1979): Much like a Herbie Hancock or Miles Davis album, one comes to a Bernie Worrell album with impossibly high expectations. Unfortunately, the piano prodigy and key P-Funk keyboardist/writer/arranger/musical director/conceptualist’s 1979 solo recording debut – unlike any other P-Funk act, on Arista Records – is, perhaps, the least notable album in the entire P-Funk catalog and probably the least interesting album that ever carried Mr. Worrell’s name. Seemingly cobbled together from P-Funk’s studio leftovers, All The Woo In The World comes across as an audio typo, a mistake that seems heaped on Worrell’s shoulders. Nearly absent is any evidence of the wizardry Worrell used in the studio to build some of the most notable music of the 20th century. Indeed, other than taking a majority of the lead vocals, Worrell the writer and Worrell the keyboard maestro seems not to ever have been a consideration for the first album bearing his own name. The songs aren’t that bad, but none are all that interesting. “Woo Together” gives birth to Worrell’s enduring “Woo” concept, which was probably derived from the “Pleasure Principle” song he co-wrote and arranged for Parlet’s 1978 album of the same name and is most notable for Motown arranger David Van De Pitte’s funky strings. The soulful “I’ll Be With You” is a mostly vocal piece that turns out to be the album’s most interesting track, capped off with Bernie’s Ramsey Lewis-like piano solo overdubbed atop his own electric ruminations. The otherwise negligible “Happy To Have (Happiness On Our Side)” also benefits from a pokey piano solo, but Worrell plays it as if he’s not sure whether it will be faded out in mid-thought or erased in the final edit. “Much Thrust” is tailor-made Funkadelic, but the guitar (probably by Mike “Kidd Funkadelic” Hampton) dominates where Worrell should. The silly Parliament-like “Insurance Man For The Funk” puts P-Funk overlord George Clinton out in front, welcomes the Horny Horns, features Maceo Parker’s noodling, gets a brief Bootsy respite and evidences some of the keyboard sounds Worrell was heard to layer on other P-Funk classics. But while “Insurance Man For The Funk” has become a cult classic, it keeps plodding along long after the simple groove is worn thin and the joke has been beaten to death (it also has one of the most anti-climactic bridges in all of P-Funk’s funkentelechy). All The Woo In The World is certainly some of the least interesting P-Funk ever waxed. But Bernie Worrell, who sounds like he’s along on someone else’s ride, deserved a whole lot better start than this. Check out Blacktronic Science (Gramavision, 1993) or Improvisczario (Godforsaken Music, 2007) to hear the wonderful Woo of Bernie Worrell. Also, see the riveting documentary, Stranger: Bernie Worrell on Earth (2007) to experience the great Bernie Worrell on a number of worthy and well-deserving planes of appreciation and acceptance.

All The Woo In The World - Bernie Worrell (Arista, 1979): Much like a Herbie Hancock or Miles Davis album, one comes to a Bernie Worrell album with impossibly high expectations. Unfortunately, the piano prodigy and key P-Funk keyboardist/writer/arranger/musical director/conceptualist’s 1979 solo recording debut – unlike any other P-Funk act, on Arista Records – is, perhaps, the least notable album in the entire P-Funk catalog and probably the least interesting album that ever carried Mr. Worrell’s name. Seemingly cobbled together from P-Funk’s studio leftovers, All The Woo In The World comes across as an audio typo, a mistake that seems heaped on Worrell’s shoulders. Nearly absent is any evidence of the wizardry Worrell used in the studio to build some of the most notable music of the 20th century. Indeed, other than taking a majority of the lead vocals, Worrell the writer and Worrell the keyboard maestro seems not to ever have been a consideration for the first album bearing his own name. The songs aren’t that bad, but none are all that interesting. “Woo Together” gives birth to Worrell’s enduring “Woo” concept, which was probably derived from the “Pleasure Principle” song he co-wrote and arranged for Parlet’s 1978 album of the same name and is most notable for Motown arranger David Van De Pitte’s funky strings. The soulful “I’ll Be With You” is a mostly vocal piece that turns out to be the album’s most interesting track, capped off with Bernie’s Ramsey Lewis-like piano solo overdubbed atop his own electric ruminations. The otherwise negligible “Happy To Have (Happiness On Our Side)” also benefits from a pokey piano solo, but Worrell plays it as if he’s not sure whether it will be faded out in mid-thought or erased in the final edit. “Much Thrust” is tailor-made Funkadelic, but the guitar (probably by Mike “Kidd Funkadelic” Hampton) dominates where Worrell should. The silly Parliament-like “Insurance Man For The Funk” puts P-Funk overlord George Clinton out in front, welcomes the Horny Horns, features Maceo Parker’s noodling, gets a brief Bootsy respite and evidences some of the keyboard sounds Worrell was heard to layer on other P-Funk classics. But while “Insurance Man For The Funk” has become a cult classic, it keeps plodding along long after the simple groove is worn thin and the joke has been beaten to death (it also has one of the most anti-climactic bridges in all of P-Funk’s funkentelechy). All The Woo In The World is certainly some of the least interesting P-Funk ever waxed. But Bernie Worrell, who sounds like he’s along on someone else’s ride, deserved a whole lot better start than this. Check out Blacktronic Science (Gramavision, 1993) or Improvisczario (Godforsaken Music, 2007) to hear the wonderful Woo of Bernie Worrell. Also, see the riveting documentary, Stranger: Bernie Worrell on Earth (2007) to experience the great Bernie Worrell on a number of worthy and well-deserving planes of appreciation and acceptance. Say Blow By Blow Backwards - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1979): The second Horny Horns album has its share of interesting moments. But the disjointed, unfocused music and its odd and not very clever title (seemingly suggesting an anagram) suggest there may have been a contractual obligation here. It’s almost as if there wasn’t the time or the inclination to put a good Horny Horns record together in the first place. But this was also the year of such ambitious – and ultimately unsuccessful – concepts as Gloryhallastoopid and Uncle Jam Wants You. Significantly, it’s also one of the few P-Funk albums that carries few writing credits for George Clinton, suggesting his input was minimal or entirely negligible. The album opens with Bootsy Collins’ light-weight anthem, “We Came To Funk Ya,” a prototypical Rubber Band chant that seems like little more than a “Bootzilla” knock-off with Wesley and Parker taking marginally interesting solos, driven along by Bootsy’s distinctive bass. Up next is Billy (Bass) Nelson’s excellent “Half A Man,” a soulful rocker that would have sounded right at home on either a Funkadelic album (circa 1976) or a Parliament album (circa 1975-76). Trouble is, it just doesn’t sound right here. Fred and Maceo only factor in the background horn charts as they did so beautifully on so many P-Funk albums at the time. But here, it’s not about either one of them at all. So even at nine and a half minutes, there’s surprisingly little Horny Horn action and a song that probably deserved to be a hit never found its way out of this half-baked album. Wesley’s title track is a key moment for the Horny Horns, a great groove and some of the most substantial improvising both Parker and especially Wesley ever laid down on a P-Funk track. This one and Wesley’s other contribution here, the fun and fascinating “Circular Motion,” are the ones to hear and probably the only two songs that deserve the Horny Horns moniker. “Mr. Melody Man” is a feature for Maceo, who gets the lion’s share of solos throughout (just like in the Rubber Band, where Maceo also served as MC) – leading one to wonder how or why the P-Funk organization never gave Maceo any of his own solo albums. “Just Like You,” originally heard with vocals on The Brides of Funkenstein’s album Funk of Walk (Atlantic, 1979), is here turned into the type of power ballad Giorgio Moroder made famous the following year with his love theme to American Gigolo (“The Seduction”). It’s another feature solely for Maceo Parker. But at six minutes and 47 seconds and umpteen musical climaxes, it’s far too long and loses steam long after the minimal passion that was there in the first place is gone (the Brides milked it for a full nine minutes!). Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a player here, would have never let that happen. Seems there are a great many pieces of fat here that a good overlord or musical doctor would have trimmed or never allowed. Still, there’s probably 21 worthy minutes of music here that are worth checking out. Unfortunately, it’s hardly enough to justify a full album, much less a CD, release. For completists, a third Horny Horns album titled, ironically (and humorously) enough, The Final Blow was issued on CD in 1994. Comprised of outtakes and unfinished numbers – which Fred Wesley has since disavowed – it completes the unfortunately slim and artistically unsatisfying discography (especially compared to the J.B.’s output) of the otherwise brilliant Horny Horns.

Say Blow By Blow Backwards - Fred Wesley and the Horny Horns featuring Maceo Parker (Atlantic, 1979): The second Horny Horns album has its share of interesting moments. But the disjointed, unfocused music and its odd and not very clever title (seemingly suggesting an anagram) suggest there may have been a contractual obligation here. It’s almost as if there wasn’t the time or the inclination to put a good Horny Horns record together in the first place. But this was also the year of such ambitious – and ultimately unsuccessful – concepts as Gloryhallastoopid and Uncle Jam Wants You. Significantly, it’s also one of the few P-Funk albums that carries few writing credits for George Clinton, suggesting his input was minimal or entirely negligible. The album opens with Bootsy Collins’ light-weight anthem, “We Came To Funk Ya,” a prototypical Rubber Band chant that seems like little more than a “Bootzilla” knock-off with Wesley and Parker taking marginally interesting solos, driven along by Bootsy’s distinctive bass. Up next is Billy (Bass) Nelson’s excellent “Half A Man,” a soulful rocker that would have sounded right at home on either a Funkadelic album (circa 1976) or a Parliament album (circa 1975-76). Trouble is, it just doesn’t sound right here. Fred and Maceo only factor in the background horn charts as they did so beautifully on so many P-Funk albums at the time. But here, it’s not about either one of them at all. So even at nine and a half minutes, there’s surprisingly little Horny Horn action and a song that probably deserved to be a hit never found its way out of this half-baked album. Wesley’s title track is a key moment for the Horny Horns, a great groove and some of the most substantial improvising both Parker and especially Wesley ever laid down on a P-Funk track. This one and Wesley’s other contribution here, the fun and fascinating “Circular Motion,” are the ones to hear and probably the only two songs that deserve the Horny Horns moniker. “Mr. Melody Man” is a feature for Maceo, who gets the lion’s share of solos throughout (just like in the Rubber Band, where Maceo also served as MC) – leading one to wonder how or why the P-Funk organization never gave Maceo any of his own solo albums. “Just Like You,” originally heard with vocals on The Brides of Funkenstein’s album Funk of Walk (Atlantic, 1979), is here turned into the type of power ballad Giorgio Moroder made famous the following year with his love theme to American Gigolo (“The Seduction”). It’s another feature solely for Maceo Parker. But at six minutes and 47 seconds and umpteen musical climaxes, it’s far too long and loses steam long after the minimal passion that was there in the first place is gone (the Brides milked it for a full nine minutes!). Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a player here, would have never let that happen. Seems there are a great many pieces of fat here that a good overlord or musical doctor would have trimmed or never allowed. Still, there’s probably 21 worthy minutes of music here that are worth checking out. Unfortunately, it’s hardly enough to justify a full album, much less a CD, release. For completists, a third Horny Horns album titled, ironically (and humorously) enough, The Final Blow was issued on CD in 1994. Comprised of outtakes and unfinished numbers – which Fred Wesley has since disavowed – it completes the unfortunately slim and artistically unsatisfying discography (especially compared to the J.B.’s output) of the otherwise brilliant Horny Horns. Sweat Band - Sweat Band (Uncle Jam, 1980): Between 1976 and 1979, Bootsy’s Rubber Band was a hugely successful offshoot of the P-Funk mothership, distinguished by equal parts funk (emphasizing Bootsy’s “Space Bass”) and silky soulful balladry. Despite Collins’ cartoon-y antics and somewhat goofy lyrics, the Rubber Band was often more “musical” than the rest of P-Funk, probably due to the high musicianship Collins himself brought to the endeavor. Very little that could be considered jazz or jazzy came out of it all but the music was tight and much more disciplined than the other P-Funk units, something Mr. Collins no doubt gleaned from his time with James Brown. The Horny Horns were featured heavily throughout, with Fred Wesley covering the charts and sidekick/emcee Maceo getting a high dose of solo spots. The best stuff out of the Rubber Band showed how well it all worked. Sample “Stretchin’ Out,” “Psychoticbumpschool” and “Another Point of View” from Stretchin’ Out In Bootsy’s Rubber Band; “Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy Baby,” “The Pinocchio Theory,” and “Rubber Duckie” from Ahh…The Name Is Bootsy Baby; “What’s The Name Of This Town,” “Bootzilla” and “Roto-Rooter” from Bootsy? Player of The Year; and “Bootsy Get Live” and “Jam Fan” from This Boot Is Made For Fonk-n. By 1980, Bootsy spread his wings a bit and launched the Sweat Band, a more instrumental version of the Rubber Band, on George Clinton’s newly devised CBS subsidiary, Uncle Jam Records. The album opens with the bracing electro-instrumental, “Hyper Space,” nearly disclaiming any similarity to anything in the P-Funk cannon and nothing at all like the Rubber Band. Driven by synth-man and co-writer Joel “Razor Sharp” Johnson and peppered nicely by guitarist Mike Hampton, it almost suggests a European action film theme of the time – a great dance piece, which could work well to highlight action on the silver screen – or just as effectively on the mirror-balled dance floor. This is the kind of thing everyone was hoping Prince would come up with at the time. Next follows the dance hit “Freak To Freak,” a good groove that suggests what the next phase of Bootsy’s Rubber Band could have been but never was - groovy guitar, funky bass, electric drums and programmed handclaps. (Sweat Band was issued on CD in Japan in the 1990s and is now long out of print, but “Freak To Freak” appears on 6 Degrees of P-Funk: The Best of George Clinton and his Funky Family, a CD compilation of Clinton’s Columbia projects made during the 1980s.) “Love Munch” is a poppy piece of jazz fusion that sits easily alongside anything Spyro Gyra was doing at the time, were it not for Maceo Parker’s gripping and hiccupping sax taking it somewhere stratospheric that’s well worth following. With Bootsy’s aggressive “Space Bass” and all-over-the-map percussion, “Jamaica” is the closest Bootsy and Maceo ever came to successfully melding the J.B’s sound with the P-Funk groove. The chant “Jamaica – take me to your jungle” paves the way for Bootsy’s Rubber Band’s next stop, a decade later, on the funky career overview, “Jungle Bass” (4th & B’way, 1990). “Body Shop” and “We Do It All Day Long” (heard in brief on side one before the full version, subtitled “Reprise,” is heard on side two) sound like above average P-Funk grooves left off of other P-Funk albums because they are straight party tunes and not sci-fi concepts or some off-the-wall comical piece. Both are Bootsy conceptions co-written with P-Funk guitarist and vocalist Gary Shider, with the Brides of Funkenstein and Parlet chanting throughout in a typical David Bowie-meets-Fred Flinstone sort of wackiness. Bootsy’s Space Bass drives both pieces along with enormous propulsion, highlighted by some tasty keyboard work that is, sadly, not by Bernie Worrell, who is listed as a contributor here. Sweat Band ranks high among P-Funk’s 1980 output, which included Parliament’s regrettable Trombipulation and Bootsy’s inconsequential Ultra Wave, easily making this one of the essential P-Funk albums to own, despite the presence of one of the worst and least P-Funk looking album covers in the entire P-Funk discography (other than the 1983 P-Funk All Stars album Urban Dancefloor Guerrillas).