Forty years ago this month, one of the last of the original CTI releases found its way onto American record-store shelves. But hardly anyone noticed. The shame of it is that Art Farmer and Joe Henderson’s Yama is a terrific record – and one that pointed the way to a new “CTI sound” that could have accorded well in the post-fusion Eighties.

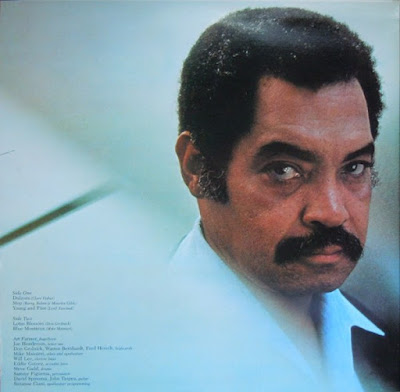

Surprisingly, Yama represents the only time trumpeter Art Farmer had ever recorded with Joe Henderson – though, even here, they may not have been in the studio at the same time. While trumpeter and “flumpeter” (a flugelhorn-trumpet combo) Art Farmer (1928-99) had a busy solo and studio career in the Fifties and Sixties, he had done very little work under the auspices of Creed Taylor, other than several early sessions for Oscar Pettiford, Candido and Quincy Jones.

Yama was the last of five albums Farmer recorded for CTI between 1977 and 1979 (he also appeared on CTI albums by Bob James, Yusef Lateef and the 1990 all-star Rhythmstick). Farmer had been living in Vienna since 1968, yet all but one of his CTI LPs were recorded in New York – excepting the Japanese-only Live in Tokyo.

Remarkably, Yama is one of only a handful of tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson’s (1937-2001) recordings produced by Creed Taylor. Henderson could be heard on a few tracks of George Benson’s Tell it Like it Is (1969), Freddie Hubbard’s Red Clay (1970) and Straight Life (1971 - Hubbard and Henderson had earlier co-led a group called The Jazz Communicators), Ron Carter’s All Blues (1973) and a favorite of mine, Johnny Hammond’s massive Higher Ground (1973).

Curiously, though, Henderson appears on one song from a 1979 Ben Sidran album The Cat and the Hat - arranged and co-produced by Yama’s Mike Mainieri – “courtesy of CTI.” The label’s waning fortunes at the time likely prevented any further releases by Joe Henderson on CTI. But you have to wonder what else may have been recorded and remains unreleased.

Interestingly, both Farmer and Henderson were born in Iowa. But it’s there the similarities end. Farmer got his chops in Los Angeles while Henderson honed his in Detroit and a later stint in the Army. Farmer had long been in New York by the time Henderson arrived in the early Sixties. By then, Farmer’s Jazztet was winding down and his quartet with Jim Hall was kicking into gear.

Henderson made a name for himself on Kenny Dorham’s “Una Mas” and Horace Silver’s hit “Song for My Father, factoring on some 30 Blue Note albums, including five of his own. As Farmer headed off to Europe, Henderson made a string of highly underappreciated records for Milestone between 1968 and 1976, during which time he permanently relocated to San Francisco.

How Farmer and Henderson’s paths ever crossed in the first place is something of a miracle. Yama is that miracle, one of two paths that really should have crossed much more often but surprisingly didn’t. The record was recorded in April 1979 (and there is likely much more than the five tracks heard here) and although it was announced as a forthcoming release later in the year, CTI ran out of funding and this and several other discs were not released stateside. Yama was, however, issued in Japan that year but was not released in the US until May 1982.

The record’s sound and success – and, most likely, its programming – are due in no small measure to the participation of composer, arranger, producer, keyboardist, percussionist, and, oh yeah, vibes player Mike Mainieri. Although, to be fair, drummer Steve Gadd and synthesizer programmer Suzanne Ciani had appeared on all three of CTI’s 1979 productions. Mainieri (b. 1938) made a splash in the Sixties playing the electric vibraphone – sounding as mellifluous as the Fender Rhodes and far less fuzzy than Gary Burton’s electric vibes – but never really broke out the way Burton and Bobby Hutcherson did during those years.

By the late sixties Mainieri began to take an interest in rock: not merely “fusion,” as such but rock. He formed the NYC musical collective White Elephant – featuring many players who would go on to CTI session work, including Warren Bernhardt and Steve Gadd here – and could be heard on later hits by Don McLean, Aerosmith and Billy Joel.

By 1979, Mainieri was doing loads of session work and began producing pop acts like Carly Simon, with whom he produced and co-wrote the 1980 hit “Jesse” (and later orchestrated her magnificent jazz album Torch with the especially haunting “I Get Along Without You Very Well”). Mainieri had also worked with Creed Taylor on productions for Kenny Burrell, Wes Montgomery, Paul Desmond, Urbie Green and, notably, Art Farmer’s previous CTI album with Jim Hall, Big Blues.

While Farmer and Henderson here might have seemed to fill roles that the Brecker brothers would have otherwise occupied, they are both game and deliver the goods – with the force of their by-then wholly distinctive personalities.

The album opens with Clare Fischer’s festive “Dulzura” (Spanish for “sweetness”). It's an inspired choice. Remarkably, for a Fischer melody, this memorable tune, which debuted on Clare’s 1965 album Manteca!, has had almost no coverage apart from Yama and a 1965 cover by the Jazz Crusaders (that also featured CTI stalwart Hubert Laws).

The Bee Gees’ little-known “Stop (Think Again)” (originally on the group’s first post Saturday Night Fever album Spirits Having Flown) elicits the Brothers Gibb’s – particularly brother Barry’s – remarkable ear for strong, albeit unusual melodies.

Joe Zawinul’s peculiar “Young and Fine” had originally appeared the year before on the Weather Report album Mr. Gone, a song which also featured Yama drummer Steve Gadd. Mainieri’s group, Steps (a group seemingly modeled on Weather Report that later evolved in to Steps Ahead), featured a take of “Young and Fine” on its 1981 Japanese-only album Smokin’ in the Pit - also with Yama’s Don Grolnick, Eddie Gomez and Steve Gadd.

Grolnick, long an undervalued composer and a player whose sensitivities mesh to perfection with Mainieri (witness the much later Medianoche), provides his compelling Latinate “Lotus Blossom,” a tune he first recorded on David Sanborn’s 1978 album Heart to Heart (also featuring Mainieri). Michael Franks added lyrics to his 1980 version of the song on the album One Bad Habit while Sanborn and Grolnick would wax the song again on the 1984 album Straight to the Heart.

Closing out the set is “Blue Montreux,” Mainieri’s magnificent title track to a particularly good album co-led by Mainieri and Warren Bernhardt – later billed as “The Arista All-Stars” – and recorded at the July 1978 Montreux Jazz Festival. While it rounds out the album, it seems to call out here for an encore that never comes.

”In Yoga,” the liner notes tell us, “Yama is the first rung on the ladder toward the gateway to self-realization. Yama is also the Japanese word for mountain.” It goes on to say “Yama can be as big as a mountain or as silent as archways in a formal garden.”

Oddly, though, the 1982 American release of the album omits why the album derived this particular title. From the 1979 Japanese release come these additional words, credited to former DownBeat editor Arnold Jay Smith (who also penned the 1995 notes to the CD release of another 1979 CTI album released stateside in 1982, La Cuna by Ray Barretto):

“The Yoga synthesis came to us from an interview Art Farmer gave to CBS Radio in which he echoed his friend Julian “Cannonball” Adderley’s approach to his art.

”’First you get together with yourself. Then you get together with your instrument. Finally, you arrive at direct communication – with the people you are playing with and those you are performing for.’”

That’s what Yama is really all about: good communication. For this listener, Yama is a success that leaves you wanting more. And that’s its only fault: Yama ends after a mere 33 breezy minutes.

2 comments:

The article is interesting only in that it alludes to a sixth track which exists on the pressing but is omitted everywhere else. The LP’s pressing (RVG-87752) is only slightly different from the label (Ste-87752). None of the track times match what’s on the label. Researching Van Gelder (a Master By credit etched in the platter) come up dry as well as Creed Taylor, Inc. A mystery track and possible track shuffling. Anyone have any answers?

Post a Comment